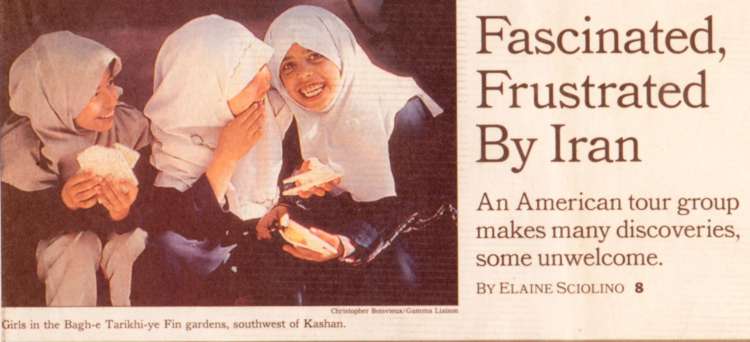

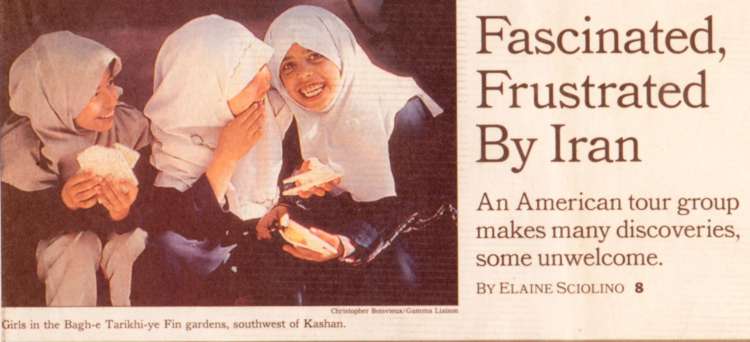

"Trip of Discoveries, Some Unhappy, in Iran"

Elaine Sciolino

The New York Times

February 28, 1999

The group of female American tourists danced a crowd-stopping dance of the veil. Outside the vast shrine in the center of Mashad, Iran, the women struggled with their chadors, shroudlike garments that cover all but the face and must be secured with one hand held under the chin. There are no hooks or zippers to make the job easier.

It wasn't enough that we were already wearing scarves on our heads and loose garments that hid the shape of our torsos. This was the holiest pilgrimage site in Iran, the place where Imam Reza, the eighth of the 12 imams, or religious leaders, in Shiite Islam, died in the ninth century and is buried. And even though the shrine itself was off limits to non-Muslims, we were allowed to walk through the outer courtyard, watch an informational film at a foreign reception center and tour the useums on the vast compound. But only if we disguised ourselves in the veils that our guide handed out as we merged from our bus.

Iranian schoolchildren giggled at the sight. A grizzled Iranian man asked to have his picture taken with us. One of the men in our group threw his sportcoat over his head and jumped into the picture.

"It's the equivalent of feet-binding in China, anything to keep women off-balance!" complained Isabel Jacobs, a retired history teacher from Riverdale, in the Bronx.

"Before I came here, I believed in women's liberation," said Dorothy Wright, a retired teacher of English literature from Middletown, N.J. "Now I believe in women's domination!"

Even I, who have been going to Iran as a journalist for 20 years, have never gotten used to this unwieldy garment, which lets me take notes only if I hold it together in my teeth.

In the early years of Iran's 1979 revolution, tourists -- particularly American tourists -- were considered dangerous invaders bent on sullying Islamic purity with Western culture. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the father of Iran's revolution, liked to rant about "the Western sickness among us," stating plainly that "there is no fun in Islam." Indeed, I never went to Iran for the night life.

These days, American tourists are no longer considered as ugly as they once were. Iran's regime is beginning to smile back, luring them with its treasures: the monumental ruins of ancient Persia, the intricately patterned mosques of Islam, the glittering palaces of the shahs, the landscapes of snowcapped mountains and rice paddies and palm-studded deserts. For about two years, intrepid Americans have ventured in, most of them on group tours organized by American and Canadian companies, but some on customized private visits.

The pace of the visits quickened after January 1998, when Iran's smiling President, Mohammed Khatami, used an interview with CNN to initiate a "cultural exchange" of intellectuals, artists and tourists to break down what he called "the wall of mistrust" between the United States and Iran. The steep drop in oil prices in the past year has contributed to Iran's eagerness to attract dollar-carrying Americans.

The family and friends of my 18 traveling companions thought they were crazy to come. We were, after all, in a country that the Clinton Administration considers the world's most active fomenter of terrorism, that once held American diplomats hostage and that has no official relations with the United States. Consular matters are handled by the Swiss, whose country represents American interests.

Indeed, in late November, just days after our return home, a bus carrying 17 American business executives returning to their hotel from the airport was attacked by a small band of angry young men wielding clubs and bats who smashed the bus windows and chanted in Farsi, "God is great! Death to America!"

The driver sped off across town to another hotel, where the group sought refuge until they could make it safely back to their own. The Americans remained under the protection of the Swiss. The Swiss Ambassador escorted the group to the airport for its departure the next night.

Shortly before the attack, a hard-line newspaper had announced that the group included spies disguised as tourists. And afterward, the organization claiming responsibility issued a communique stating, "Your children performed their first operation against American spies." It added, "Iran is no place for American Yankees and our next operation will be the performance of our slogan 'Death to America.' "

No one was injured; Iranian officials loudly condemned the attack and American visitors have been left unharmed since then. But the incident was a chilling reminder that Iran is not a benign place, even to visit. And it just as easily could have been our group, which included a retired Navy captain and a retired Foreign Service officer.

But our small band was intrepid, well traveled and well prepared. Members talked knowingly of the volcanic sands of Guatemala, the cashews of Mozambique, the barracudas of Belize. They carried medical kits that included sutures and hypodermic needles. They knew how to check the tires of domestic airplanes. They could find the 24-hour supermarket in Teheran to buy caviar and the synagogues in Isfahan on their own.

Our 14-day journey took us through Teheran, Mashad, Kermanshah, Hamadan, Kerman, Bam, Yazd, Shiraz, Persepolis, Isfahan, Kashan and Qum. We were free to go wherever we wanted and, except for military installations, airports, mosque interiors and some museums, took photographs as we wished.

The Americans came for various reasons. Lois Clark, a retired teacher, and her husband, Daniel, a retired radiologist, from Iowa, were struggling to understand the culture that shaped their Iranian-born son-in-law. Martha Habermann, who runs a nursing home in upstate New York, called it "the frisson of doing something adventurous." Ronald Endeman, a lawyer from San Diego, counted Iran as the 235th country he has visited so far (but then, he counted places like Sicily and Hawaii as countries, too).

Our guide was Hossein Shams-ol-mali, a retired teacher who couldn't quite support himself and his wife on his small pension. No matter that his English was flawed and his explanations opaque. Mr. Shams, as we called him, was a gentleman, ever patient with our endless questions. (Why are there no dogs on the street? Do Jews serve in the Army? Do dervishes really whirl?) He also played bellman and waiter when necessary.

Our tour was run by Bestway Tours and Safaris, of Vancouver, British Columbia, although several of us who had booked through Absolute Asia, a New York-based company, didn't know that until we arrived. We also discovered that Bestway had charged tour members only $2,790 for their trip, excluding air fare; we had paid Absolute Asia $3,125. Absolute Asia explained in a letter that the additional cost covered "personalized itinerary planning" as well as visa processing. (In fact I had arranged my own visa.)

Iran's tourist infrastructure functions surprisingly well, considering how few high-paying tourists have ventured in over the last two decades. The hotels built during the oil boom of the 1970's have seen better days, but have been renovated and function fairly well. Domestic air travel is cheap, remarkably safe and on time. Pharmacies are well stocked. Persian cuisine is a delight (when one can get away from the ubiquitous kabobs); fresh fruits and vegetables are grown throughout the country, and in Teheran the tap water is considered better than the bottled variety.

But our tour bus was in need of repair and cleaning. The air-conditioning blew hard through the holes where overhead lights should have been. There were no seat belts and no toilet. The choking air pollution from leaded gasoline fumes can be troubling for people with respiratory problems, particularly in the big cities such as Teheran and Isfahan.

Except at the mosques, the women in our group took risks with their dress almost from the start. Our guide made the mistake of telling us at our first orientation that we did not have to wear the poorly sewn, ankle-length polyester coats handed out at the beginning of the tour. So some women donned their husbands' shirts over pants and exchanged their scarves for hats. It was unseasonably hot, so we even dared to go bareheaded on the bus, which elicited wide-eyed stares (but no arrests).

Still, there were uncomfortable incidents when perfect strangers told us we were misbehaving. For instance, when one female tour member posed for a photograph with a group of giggling Iranian women in their chadors in Mashad, a man barked at the women not to allow their faces to be photographed.

Bending the rules did not extend to alcohol. When security guards at Teheran's Mehrabad Airport discovered several tiny bottles of liquor in the suitcase of one tour member, there were threats to confiscate our luggage, hold up our departure and even try the alleged culprit in an Iranian court. Eventually, the security guard and airport police were paid off; we made our flight.

There were times when political reality and the official animosity toward the United States intruded. Some of my fellow travelers were offended by a neon sign at Teheran's airport announcing in English that, "In future, Islam will destroy Satanic sovereignty of the West."

"With one hand they're telling us we're demons," said Ms. Wright. "With the other hand, they're taking our money."

We happened to be in Isfahan on the 19th anniversary of the seizure of the United States Embassy in Teheran, which began the 444-day nightmare of American diplomats held hostage and led to the rupture of diplomatic relations with Iran. Banners hanging throughout the city proclaimed "Death to America" in Farsi and "Down With U.S.A." in English. We were kept far away from the city's demonstration -- largely of schoolchildren bused in for the event -- at a sports stadium.

The lead story on the television news that night showed footage from demonstrations in more than a dozen cities around the country. The only problem was that some of the footage obviously came from the archives. Still, members of our group were not amused. "I've been smiling at people up to now," said Fritz Wright, a retired engineer. "At this point I don't know whether to smile at them or not."

Our tour did not include a drive-by of the confiscated American Embassy compound in Teheran, for years a school for training revolutionary guards. But I took two of the members of our group for a firsthand look on our last day. Its walls had been freshly painted with anti-American images, including a giant head of a skeleton as the Statue of Liberty.

Throughout the trip, the official animosity towards the United States Government contrasted sharply with the shock and sheer joy of ordinary Iranians in encountering Americans who liked Iran well enough to come touring. "In China, people come up to you and talk, but they don't kiss you and say they love you like they do here," said Ms. Habermann. When I told a porter in the hotel in Hamadan, which is off the foreign tourist track, where I was from, he looked bewildered. "Who let you in?" he asked.

What makes it especially difficult to penetrate the country is that Iranians operate in two worlds. Behavior is much more relaxed in the privacy of one's home, where even the most devout Muslim women remove their head coverings. And in secular families, one may even be offered a shot of bootleg vodka or a glass of homemade wine. For the most part, our group operated in a parallel universe, seeing the externals.

But there were moments of discovery, many of them disheartening. Katharine Loring, an emergency room nurse and bicyclist, said that Iran would be a great place to take a bike trek, but then learned that men and women must ride bikes on segregated tracks. Mr. Endeman, the lawyer, gave a young Iranian woman friend of mine a good-bye hug in front of our hotel in Shiraz, and she recoiled in fear: Men and women who are not close relatives are not even supposed to shake hands.

Inside the shrine of the brother of Imam Reza in Shiraz, where women wept and moaned as they begged God for favors, Ms. Loring cuddled the baby of a mother of two. "Take my baby to America," the mother said matter-of-factly. "She is better off growing up there." When Ms. Loring balked, the woman said she could take her 7-year-old daughter instead, much to the horror of the girl, who clutched her mother's leg.

The American women were incensed that Iranian women have to ride in the back of the bus. And then there was the incident of the restaurant toilets in in Shiraz. The men's was a familiar Western, chairlike model; the women's was, as in most places, a porcelain hole in the ground that required squatting. The women simply barged past the male attendant into the men's room.

And it was those restrictions, those arbitrary limits on freedom, that irritated Mel Jiganti, a retired judge from Chicago who came carrying a paperback copy of the Koran. "The only other place I've ever felt like this was in the Army, when I had a sergeant who had arbitrary power over me," he said.

Then the magic of Iran took over.

We sought refuge from the stares and smog on the footpaths of the enormous Bagh-e Eram in Shiraz, a sprawling public garden filled with 200-year-old cypress, pomegranate, salt cedar and sour cherry trees, musk roses, coxcomb and honeysuckle.

We soaked in the view of palm groves in the desert from the top of the medieval mud-walled citadel and town at Bam, then sipped mango juice at a charming teahouse there run by an Iranian woman who beckoned with the words, "We are waiting for you."

We left the world of Shiite Islam far behind in Hamadan at a mausoleum with a basket of yarmulkes at the entrance and a wall engraved with the Ten Commandments in Hebrew. There, according to legend, Esther and Mordecai are buried.

We discovered a wedding reception at our hotel one evening in Shiraz and ventured in for a peek. The sister of the bride introduced us around to the other women, dressed in fancy cocktail dresses, their hair lacquered, their faces beautifully made up. They danced in a conga line led by the bride. The men, meanwhile, were banished to a separate room, just as at an Orthodox Jewish wedding.

But it was Persepolis, the seat of Persia's ancient kings and Iran's most important archeological treasure, that awed the Americans. Walking through the vast remains of the palace started in the sixth century B.C. by Darius the Great reduced our garrulous group to few words. So should Americans who have been everywhere else go to Iran? "If you wait until it gets more efficient, all the spontaneity and surprise will be lost," said Cynthia Katz, a part-time travel agent from Nyack, N.Y., as we walked through the vast, perfectly proportioned 17th-century square in the center of Isfahan. "When this place starts looking like the Sistine Chapel with wall-to-wall people, it's not going to be fun anymore."

But Thomas H. Miner, the chairman of the Chicago-based Mid-America Committee, who had led the tour of the Americans who were attacked, admitted in an interview that he might have gone to Iran too soon. "I don't think Iranians are ready for Americans -- even tourists," he said. "I don't think there is anyone in that country who can protect you."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Dear Editor:

I am writing in response to Elaine Sciolino's story about the disappointments she and her tour group experienced while traveling in Iran (Travel, 2/28/99). Ms. Sciolino and her travel companions seemed to complain incessantly about having to wear scarves, chadors and loose clothing, about norms against men and women showing affection in public, about the lack of flush toilets for women, and about many other things. While she describes her companions as an intrepid and resourceful group who had traveled to such varied places as Mozambique and Guatemala and who could locate the 24-hour supermarket that sold caviar in Tehran, what I see is a privileged group of Americans (one of whom apparantly measures the depth of his cross-cultural experience by counting the number of countries he visited, including Sicily and Hawaii in his list of countries!) who traveled thousands of miles to Iran and then became disappointed that they did not find America when they arrived there.

What did Ms. Sciolino and her companions expect to find in Iran? Perhaps it would have paid them to do a little more research before spending nearly $3,000 on their trip. If they did know what to expect and went anyway, why are they complaining? If they did not know what to expect, where have they been for the past two decades? How could anyone have lived in the U.S. and read newspapers for over 20 years and not know what the situation would be like in Iran? One of my undergraduate students has probably expressed this point best --"Duh!"

The pleasure of traveling to a foreign country is to enjoy the very differences that traveling to that country provides. When I am visiting another country, or even when I am visiting culturally different locations within the U.S., I respect the norms and customs of the region or the locality I visit. I don't expect Iranians or anyone else to live by my rules. Maybe, that is why all of my travel experiences have been rewarding, even the "challenging" ones.

Perhaps Ms. Sciolino and her companions should stay at home the next time and experience foreign lands via the Discovery Channel, or maybe they could visit the EPCOT Center at Disney World where they could simultaneously enjoy both palatable versions of "other cultures" and flush toilets for everyone.

William S. Abruzzi

Head, Department of Sociology and Anthropology

Muhlenberg College

Allentown, PA 18104

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

|

In addition to the more obvious impact that tourism has on those who are the object of tourist interest, there are more subtle, yet very profound, effects that tourism has on communities whose existence becomes economically dependent on tourists and tourist dollars. These effects have been discussed at length in Hal Rothman's book, Devil's Bargains: Tourism in the Twentieth Century American West. Below is a review of Rothman's book that I wrote for Human Ecology Review. . . . |

|

|

|

|

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The following article illustrates the conflict that exists in many regions of the world between the economic benefits and social costs that tourism provides for many countries in the developing world. International tourism results in repeated superordinate/subordinate contact between privileged white Europeans & North Americans and poor people of color. Tourists pay large sums of money to visit the various tourist destinations located throughout the world and, therefore, expect to be able to act more or less as they wish and be treated accordingly. This often results in the development of reciprocal stereotypic attitudes between tourists and locals, as well as in occasional hostilities.

The negative reaction to what is perceived as the exploitative aspects of tourism can be seen in Ole Kamuaro's report on ECOTOURISM: SUICIDE OR DEVELOPMENT?, published by Voices from Africa.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

|

March

6, 2002 Tourists and Islam

Mingle, Not Always Cozily

|

|

|

ZANZIBAR,

Tanzania — Zanzibar has long wrestled with its dual role as both an

Islamic society and a tourist spot, but lately a combination of bikinis,

bombs and beer has made that balancing act tougher than ever.

This

former sultanate with sand is more than 90 percent Muslim and has more

than 50 mosques crowded together in the old quarter, called Stonetown,

outnumbering its hotels and guesthouses. Many tourists who roam Stonetown's labyrinthine alleyways dress in skimpy beach attire despite advice from tour operators to cover up. It is not difficult to see in close quarters both the bikini and the buibui, as the black head-to-toe covering that local women wear is called.

"If

I want to come to your home I should follow the rules of your home,"

said the imam of one mosque, Maalim Idris Saleh. "It should be the

same for those visiting Zanzibar. We don't want people to kiss each other

on the streets. We don't want them to walk around naked." The locals complain that living as a devout Muslim can be a challenge with tourists in one's midst. But the conflict has become more violent recently as a segment of Zanzibar's Muslim community pushes a hard- line religious view.

|

Devout Muslims complain that living with tourists in one's midst can be a challenge. An imam said, "If I want to come to your home I should follow the rules of your |

|

A

series of bombings at local bars, none regular tourist haunts, has

tarnished the island's image as a tranquil vacation spot where the loudest

sound one can expect to hear is ocean waves crashing against the pristine

shore.

In

one, somebody stuck an explosive into a urinal in the men's room of the

New Happy Lodge in the Stonetown area. Porcelain shards wounded the owner

and blinded two others. Business has not been the same since.

"Help

the bomb victims," says a handwritten sign affixed to a collection

box at the bar, where a crush of locals hang out all day drinking.

Similar

explosions have rocked two other bars. A fourth tore through a vehicle

that delivers alcohol. The police have arrested five suspects in the

attacks and they say that the men may have heard anti-alcohol teachings in

local mosques and taken the religious message to the extreme.

"Up

to this moment we don't have direct evidence to link the terrorist

activities with religious convictions but we suspect that to be the

case," said Juma Mtumwa Abdallah, Zanzibar's assistant police

commissioner. Such tensions are not exactly new. People from the Middle East, Asia and Europe have visited the Indian Ocean trading center for thousands of years. As far back as 1939, the government saw fit to limit the consumption of alcohol, prohibited under Islam, to "certain classes of persons, including Europeans, Americans, Japanese, Chinese, Parsee and Goans." |

|

|

Tourism

nose-dived in 1998 after it was disclosed that one of the men involved in

the terrorist bombing of the United States Embassy in Dar es Salaam was

from Pemba, the smaller of the two main islands that make up Zanzibar.

Khalfan Khamis Muhammad, an operative working for Osama bin Laden, was

sentenced to life in prison without parole for helping to make the

explosives used to attack the embassy on Aug. 7, 1998.

Then,

last year, the government of Tanzania began a violent crackdown in

Zanzibar on members of the opposition Civic United Front who were

protesting the results of disputed elections held in October 2000. The

ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi party, based on the mainland, has set up an

independent commission to look into the dozens of killings and widespread

allegations of abuse by government security forces. |

A Muslim woman walks in Chake-Chake town in Pemba island, Zanzibar.

|

|

The

island's image did not improve after the Sept. 11 attacks in the United

States, with reports that Islamic fundamentalists were distributing lists

in some mosques seeking volunteers to aid Mr. bin Laden.

The

police began investigating all locals planning to travel overseas to

ensure that none were headed for Afghanistan. No Al Qaeda recruits were

discovered.

The

war being waged on the streets of Zanzibar is clearly more a clash of

cultures than an international battle over terrorism. Mr.

Saleh, the imam, said only a tiny number of the island's Islamic community

could be considered radicals. A vast majority lamented the attacks on the

United States, he said, and similarly did not support the smaller-scale

violence to enforce the rules of Islam.

As

for tourism, he said most Muslims embraced the economic support it brought

to the island but questioned the costs on the culture.

Occasionally, men have attacked local women for not wearing what they

considered sufficiently modest clothing. Some religious activists have

even called for the same treatment for tourists, but such a campaign has

never taken root.

"See

her? She's dressed O.K.," said a taxi driver hanging out with

colleagues outside the main museum in Stonetown. He motioned toward an

elderly woman in long pants and long sleeves. "That one's not

O.K.," he said of a woman, a tourist, wearing a skirt that fell far

above the knees. He offered his most enthusiastic approval to a

local woman, her age unclear, entirely covered in black. "That's how

women should dress," he said. The man cut his fashion critique short, however, because he had more pressing business — a group of tourists, showing far too much skin, who needed ferrying around in his taxi. |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~