When Was Jesus Born?

A Critical

Examination of Jesus' Birth Year

as

Presented in the Infancy Narratives.

William S. Abruzzi

(2016)

The current year is 2016

because the world follows a Western calendar, which calculates its years

beginning with the birth of Jesus, who most people believe was born in

Bethlehem in Judea 2,016 years ago. Nowhere, however,

does the New Testament specify when Jesus was born, and

the currently accepted year is unlikely to be correct. Indeed, only two

of the canonical gospels --Matthew and Luke-- even mention Jesus' birth. Furthermore, being

driven primarily by theological considerations rather than by a concern with

historical accuracy, the two infancy narratives not only contradict one another

in almost every detail; they also run counter to logic and are completely

unsupported by the historical evidence.

Around 525 CE, Dionysius Exiguus (Dennis

the Little), a Scythian monk living in Rome,

established the current Christian calendar based on the birth of Jesus. Dionysius was attempting to replace the existing

Diocletian calendric system (Mason 2000),1

which denoted years beginning with the reign of Gaius Aurelius Valerius

Diocletianus (Roman emperor from 284 to 305 CE), as Diocletian was known for his

persecution of Christians.

Dionysius also hoped a new calendar would

help repair a major division within the church over the dating of Easter.2

Dionysius calculated Jesus' birth date as December 25,

753 AUC (Ab Urbe Condita, "from the founding of the city"). One

speculation is that Dionysius based his date on Luke's gospel, which states,

"Jesus was about thirty years old when he began

his work" (Luke 3:23) and that this occurred

"in the fifteenth year of the reign of Emperor

Tiberius" (Luke 3:1). Tiberius' reign began

around 767 AUC, which became 14 A.D. in Dionysius' calendar. Counting

backwards, 754 AUC became 1 A.D., the year Jesus was born (see Mason 2000).

Another proposal is that Dionysius based his calculations on a tradition that

the Roman emperor Augustus reigned for 43 years, followed by the emperor

Tiberius. If Jesus was 30 years old in the 15th year of Tiberius'

reign, then he lived 15 years under Augustus, placing Jesus' birth during

Augustus' 28th year as emperor. Since Augustus became emperor in 727

AUC, Dionysius placed Jesus' birth in 754 AUC. Both methods of calculation, if

used, would have led Dionysius to 754 AUC as the year Jesus was born.

A fundamental contradiction exists, however, between

Diocletian's date for the birth of Jesus and that presented by Matthew and Luke.

Both Matthew (2:1) and Luke (1:5) place Jesus' birth in "the days of Herod",3

who died in 750 AUC, four years prior to the year designated by Dionysius (see

Barnes 1968, discussed below). The birth stories of Matthew and Luke contain yet

another contradiction regarding the date of Jesus' birth. If Jesus was born

during the reign of Herod the Great, whose actions are central to Matthew's

infancy narrative, he would have to have been born by

at least 4 BCE, and

likely earlier. This date stands in direct contradiction to the date implied by

Luke's nativity story in which Jesus was born during the census of Judea, as

that census took place in 6/7 CE.4

In order to understand this discrepancy, it is

necessary to recognize that both Matthew and Luke present

theologically driven

infancy narratives rather than historical accounts of Jesus' birth.5

Consequently, any serious evaluation of the two infancy narratives (or, for that

matter, of any biblical writings) must examine how the telling of a specific

story enhances the larger theological message of the respective author.6

For example, Matthew locates his infancy

narrative in a Palestinian Jewish context, whereas Luke situates his narrative

in the larger Gentile/Roman world. Matthew's placing of Jesus' birth during the

reign of Herod, a Jewish king; his mention of the Jewish scribes and priests;

his account of the Slaughter of the Innocents and of the escape to Egypt, as

well as his repeated insertion of Old Testament prophecies to account for those

events, places Jesus' birth squarely within a Palestinian Jewish context. Luke,

on the other hand, situates Jesus' birth during the reign of a Roman emperor and

a census conducted by a Roman governor under the instructions of that emperor.

Furthermore, instead of magi visiting "he who

has been born king of the Jews" (Matt 2: 2),

Luke has Jesus visited by shepherds who come to praise

"Christ the Lord,"

with no reference whatever to Jesus' Jewishness. Also, while Herod is mentioned

in passing to locate the time of John the Baptist's birth (Luke 1:5),7

he is not mentioned even once in relation to Jesus' birth. Thus, the significant

historical figures directing actions surrounding Jesus' birth in Matthew are

Jewish and Palestinian, whereas in Luke they are Gentile and Roman. In the

former, they are parochial; in the latter they are universal.

Raymond Brown underscores the significance of Luke's

placing the birth of Jesus in a Roman context. According to Brown, we see a

backward shift of the

Christological moment (i.e., the moment when

God reveals who Jesus is) in the New Testament from Jesus' resurrection in Paul (Romans 1:4; see also

Acts 13:32-33) to his baptism in both Mark (1:11) and Matthew

(3:17), to his birth in Luke. Significantly, according to Brown (1977:414-415),

. . . when Luke

moves the christological moment back to the conception and birth of Jesus, he

gives the birth too a setting and chronological framework of world and local

rulers, as he mentions Augustus Caesar, the emperor, and then Quirinius, the

legate of Syria. . . . [In Luke] the Roman emperor, the most powerful

figure in the world, is serving God's plan by issuing an edict for the census of

the whole world.8

The

Fourth Gospel, pushed the Christological

moment back even further. In John, Jesus was always divine. The very first

verse of the John's gospel states,

"In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with

God, and the Word was God." (John 1:1) In other words,

in John, Jesus and God are, and have always been, one. Thus, it is in John, and

in no other gospel, that when asked how he could possibly know Abraham, Jesus

replies, "Very truly I tell you, before Abraham

was born, I am!" (John 8: 57-58). Jesus became human

in John's gospel through an undefined process:

"And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us"

(John 1:14). There is, therefore, no birth story in

John because, being God, Jesus clearly pre-existed Joseph and Mary.

Of

the four canonical gospels, only Matthew and Luke contain stories related to the

birth of Jesus. Nowhere else in the entire New Testament is there even a single

mention of Jesus' birth, or of the miraculous events that purportedly surrounded

his birth. Both Mark and John begin their gospels with Jesus' baptism by John

the Baptist and contain no birth stories.9

In addition, not once in their entire gospels do either Mark or John make a

single reference to anything related to Jesus' birth. Mark never mentions

Joseph, Jesus' father, and John does not once mention Mary, his mother. Even

when the validity of Jesus' mission is challenged in John (7:40-43) because he

is from Galilee, not Bethlehem --which would have been a perfect opportunity to

mention Jesus' miraculous birth in Bethlehem-- John has Jesus and his followers

say nothing about it, suggesting that the author may not have been aware of such

a belief.

When they heard these

words, some of the people said, 'This is really the prophet.' Others said, 'This

is the Christ.' But some said, 'Is the Christ to come from Galilee? Has not the

scripture said that the Christ is descended from David, and comes from

Bethlehem, the village where David was?' So there was a division among the

people over him. (John 7:40-43)

There

is also no reference to Jesus' birth in the two dozen or more sermons in Acts

attributed to Peter and Paul or to any of the other first-generation Christian

missionaries,10 and only one reference to it in the

main Pauline letters.11

Significantly, Jesus' birth is also not mentioned in either Matthew's or Luke's

own gospels outside their infancy narratives, even where such references would

have been appropriate and supportive of Jesus' mission. This silence regarding

Jesus' birth outside the two evangelists' infancy narratives has led some

scholars to suggest that those narratives may have been added to the two gospels

later, either by the authors themselves or by others (see Conzelmann 1953;

Winter 1954, 1955; Wilson 1959; Oliver 1964; Davis

1971; Brown 1977).12

Indeed, except for their infancy narratives, which introduce completely new

information into the Jesus Story, the two gospels follow almost exactly the

chronology of Mark, using much the same wording. Furthermore, Jesus' birth story evolved over time; just

as Matthew's and Luke's infancy narratives introduced novel material into the

"Jesus story" that was not contained in any earlier sources, later Christian

writings added additional miraculous elements to the Jesus birth story not

presented by either Matthew or Luke (see McGowan 2012). The most significant of these

were the 2nd century

Protevangelium of James and

Infancy Gospel of Thomas.

(see Abruzzi

The Birth of Jesus).

The Year of

Jesus' Birth

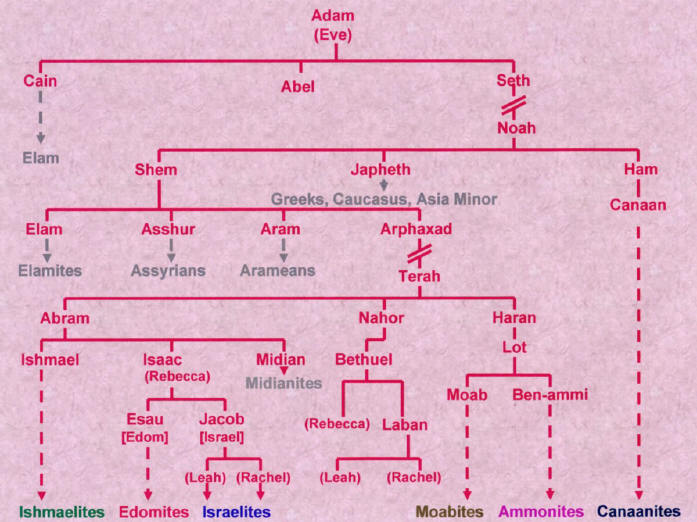

According to Mathew's gospel (and implied by Luke's gospel), Jesus was born

during the reign of Herod the Great. Herod became King of Judea by overthrowing Antigonus in 37 BCE and ending the Hasmonean Dynasty, which had ruled Judea

since the Maccabbean revolt against the Seleucid Empire in 166 BCE. Herod was a

vassal of Rome13

and served at its pleasure as long as he maintained peace in the territories

under his control, paid tribute to Rome, and supported Rome and its allies in

their wars. As mentioned previously, the consensus among scholars is that Herod

died in 4 BCE. Barnes (1968) presents the multiple, independent evidence for

this date.

1. Herod's successors (his three

sons) all reckoned the beginning of their reigns as 5/4 BCE.

2. Calculating backwards from the end

of each son's reign, likewise, confirms that all three of Herod's sons began

their reigns in 5/4 BCE.

a.

Archelaus was deposed

from the throne of Judea and banished to Gaul in 6 CE, when he was in the 10th

year of his reign.14

b.

Herod Antipas, tetrarch of Galilee lost his tetrarchy during the second year

of the reign of the Emperor Gaius (Caligula) in 39 CE, from which time coins

have survived that were minted marking Antipas' 43rd year as ruler.

c.

The end of Phillip's reign of 37 years was assigned by Josephus to the 20th

year of Tiberius (33/34 CE).

3. Josephus records that Varus was

governor of Syria when Herod died. Varus was governor of Syria from 6-4 BCE.15

4. Augustus summoned several notable

Romans, including his grandson Gaius (Caligula), to participate in a hearing in

which the three sons of Herod submitted their rival claims to succeed their

father. This was shortly after 5 BCE, when the Senate had voted that Gaius

should participate in public business. Gaius was still in Rome during the summer

of 2 BCE, after which he went to the Danube frontier.

5. Herod died shortly after a lunar

eclipse. A lunar eclipse occurred in Judea during the night of September 15, 5

BCE and again on March 13, 4 BCE. No eclipse occurred after March 13, 4 BCE

until January 10, 1 BCE,16

by which time Gaius had already left Rome, and Herod's three sons had already

assumed their positions as rulers of their respective territories.17

6. Herod was just under 70 when he

died. Josephus (Antiquities

14: 158) indicates that he was 25 in 47

BCE.18

Matthew's "Slaughter of the Innocents"

As

previously indicated, Matthew places Jesus' birth squarely during the reign of

Herod the Great. Indeed, the central dramatic event driving Matthew's infancy

narrative is Jesus' escape from Herod's slaughter of all the male children under two

years of age in the town of Bethlehem (Matt 2:16). This story, however, cannot

be given even a hint of credibility. Such an unprecedented slaughter of innocent

children would have left its mark for years on the local population, as well as

on those who documented the events of the day. Yet, despite the unparalleled

brutality represented by the heinous murder of so many innocent children, not a

single other source, Christian or non-Christian, makes any mention of this event. There is no mention of it in any Roman documents from that time period,

or in any Jewish sources, such as the Talmud and the

Mishna, both of which

contain running commentaries on local events. It is also not mentioned by Josephus, the

principle Jewish historian of that time period, who wrote in extensive detail

about events in the region, and who would have relished the opportunity to add

to the catalogue of wrongdoings by Herod. There is also no mention of a slaughter by Philo, a prominent Jewish philosopher, who

also wrote at that time. Josephus' silence on this event, given both his

detailed discussion of so many other events that took place at this time and his

particular antipathy towards Herod, is especially devastating to the credibility

of Matthew's account. Indeed, as Mason (2000) notes,

Matthew is the only Gospel

--indeed the only first-century source-- to mention Herod's murderous decree and

the holy family's subsequent flight. Not even the contemporaneous Jewish

historian Josephus, who delighted in unmasking Herod's ferocious nature, speaks

of the massacre of the innocents.

In a

similar vein, Brown (1977: 31) asks,

If Herod and all Jerusalem

knew of the birth of the Messiah in Bethlehem (Matt 2:3), and indeed Herod

slaughtered the children of the whole town in the course of looking for Jesus

(2:16), why is it that later in the ministry no one seems to know of Jesus'

marvelous origins (13:54-55), and Herod's son recalls nothing about him

(14:1-2)?

The story of Jesus'

narrow escape from death is not unique; it was a common theme in ancient legends

(see Enslin 1940: 331-332).

Indeed, it is the "stuff" of epic literature. Jesus' narrow escape from Herod's

wrath was directly modeled by Matthew on Moses' escape from the Pharaoh's

attempt to kill all Hebrew male children.

Then Pharaoh commanded all his people,

"Every boy that is born to the Hebrews you shall throw into the Nile, but you

shall let every girl live."

Now a man from the house of

Levi went and married a Levite woman. The woman conceived and bore a son; and

when she saw that he was a fine baby, she hid him three months. When she could

hide him no longer she got a papyrus basket for him, and

plastered it with bitumen and pitch;

she put the child in it and placed it among the reeds on the bank of the river.

(Exodus 1:22-2:3)

The Moses story itself may have been a direct retelling of

earlier Mesopotamian stories. For example, the

Legend of Sargon is an Akkadian story preserved

in cuneiform tablets in which King Sargon of Akkad (2270-2215 BCE) recounts how

his mother put him, as a newborn infant, in a reed basket which she then placed

in the Euphrates River, and how he was later rescued downstream. (Finkel

2014:133-135)

My mother, a high priestess, conceived me, and bore me in secret.

She placed me in

a reed quppu and

made its opening

watertight with bitumen.

She abandoned me to the river, from which I could not come up.

The river swept me along, and brought me to Aqqi, drawer of water.

Aqqi, drawer of water, lifted me up when he dipped his bucket,

Aqqi, water drawer, brought me up as his adopted son.

(Quoted in Finkel 2014:134)

As Finkel (ibid.: 135) notes,

The baby was to be one of the greatest

kings of Mesopotamia, his life saved at the outset against all odds by

a bitumen-sealed, basket-like vessel

launched on water into the unknown. The description of sealing the opening with

bitumen is a direct textual parallel to the traditional Flood Story account.

--compare

blue text in the above

two quotes.

The Moses story was also influenced by earlier flight stories in the Old

Testament, which were also centered on Egypt.

The story of the flight of Jeroboam to Egypt to

escape death at the hands of Solomon, and of his stay there until the death of

Solomon;

the even more striking story of the flight of

Hadad, as a little child, from David and Joab, busily engaged in slaying all the

males in Moab, and his return to his own country after he had heard in Egypt of

the deaths of David and of Joab

may well be pondered by the student of the

Christian nativity story. (Enslin 1940:

332).

Comparable stories also exist in Jewish tradition. In one

such story (Ginzberg 1959: 186-188; relayed in Freed 2001: 94), King Nimrod,

the great grandson of Noah, rival of Terah and

"a mighty hunter before the Lord" (Genesis

10:8-12), was informed by his astrologers (magi)

that a man would be born who would rise up against him. When Nimrod consulted

his advisors, they all agreed that he should build a large house to which he

should invite all of the pregnant women and their midwives. All of the midwives

were instructed to kill the boy babies they birthed and let only the girls

survive. In the meantime, guards were stationed around the house to prevent any

women from escaping. As a result, some 70,000 male children were killed. Abraham

survived the massacre only because the pregnant wife of Terah, his father, was

sent out of the city before the massacre began. She wandered in the desert until

she eventually found a cave, whereupon she gave birth to Abraham the following

day.

One night the star-gazers noticed, a

new star rising in the East. Every night it grew brighter. They informed Nimrod.

Nimrod called together his magicians and astrologers. They all agreed that it

meant that a new baby was to be born who might challenge Nimrod's power. It was

decided that in order to prevent this, all new-born baby-boys would have to die,

starting from the king's own palace, down to the humblest slave's hut.

And who was to be put in charge of this important task?

Why, Terah, of course, the king's most trusted servant.

Terah sent out his men to round up all expectant

mothers. The king's palace was turned into a gigantic maternity ward. A lucky

mother gave birth to a girl, and then they were both sent home, laden with

gifts. But if the baby happened to be a boy, he was put to death without mercy.

One night, Nimrod's star-gazers watching that new star,

saw it grow very bright and suddenly dart across the sky, first in one direction

then in another, west, east, north and south, swallowing up all other stars in

its path.

SOURCE:

http://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/112333/jewish/Nimrod-and-Abraham.htm

The infant Moses and Abraham escape stories (like the biblical Flood Story) long

post-date their Babylonian counterparts, and most likely became incorporated

into Hebrew tradition in part as a consequence of the "Babylonian Captivity"

(587-537 BCE), the 50-year period during which Hebrew leaders were forced to

live in Babylon where they assimilated many aspects of Mesopotamian culture.

Matthew's "Slaughter of the Innocents" story likely derived, therefore, from a

long history of Mesopotamian childhood narrow-escape stories. Given

his reputation for jealousy and paranoia, Herod served as the perfect foil in

his role as a wicked and jealous king.

Narrow escape stories

were not confined to Mesopotamian tradition; indeed, they were quite common

throughout the ancient world.

Suetonius wrote that prior to Caesar Augustus' birth a foreshadowing appeared indicating that

a future ruler of Rome had been born. This was perceived as a direct

threat by Roman senators, who forbade any boys to be born that year. Augustus,

however, narrowly escaped being killed.

. . .

a few months before Augustus was born a portent was generally observed at Rome,

which gave warning that nature was pregnant with a king for the Roman people;

thereupon the senate in consternation decreed that no male child born that year

should be reared; but those whose wives were with child saw to it that the

decree was not filed with the treasury, since each one appropriated the

prediction to his own family.

(Seutonius,

Lives of the Caesars:

2.94.3)

In a similar vein, Suetonius

recounted that during the reign of Nero,

A blazing

star, which is vulgarly supposed to portend destruction to kings and princes,

appeared above the horizon several nights successively. He felt great anxiety on

account of this phenomenon, and being informed by one Balbillus, an astrologer,

that princes were wont to expiate such omens by the sacrifice of illustrious

persons, and so avert the danger foreboded to their own persons, by bringing it

on the heads of their chief men, he resolved on the destruction of the principal

nobility in Rome. (Seutonius,

Nero:

36; quoted in Enslin 1940: 330)

France (1979:

98-99) illustrates the ubiquity of such stories.

Sargon of Akkad was

rescued from unspecified danger by being floated down the Euphrates;

Gilgamesh escaped his grandfather, whom he

was later to supplant, when an eagle caught him as he was thrown from the

acropolis after a clandestine birth;

Romulus and Remus, exposed to die on the orders of

their usurping greatuncle, were suckled by a wolf;

Cyrus, whose future power was foretold by

magi before his birth, was preserved by a herdsman who substituted his own

stillborn child for the baby he was ordered to expose;

and a Senate resolution to liquidate all

male children born in the year of Augustus' birth (because of a portent of the

birth of a king) was kept from the statute book by the self-interest of the

expectant fathers in the Senate.

Greek mythology provides further variations in the

stories of Perseus and of Oedipus, and many other cultures can follow suit.

Our own

Snow-White, with the wicked step-mother queen, the prediction by the magic

mirror, the exposure in the forest, the rescuing dwarves, and the ultimate

frustration of the witch's spell, has all the main features.

. . .

This is the stuff of which fairy-tales are made.

A key element in Matthew's tale of Herod's

slaughter is the role played by the three magi, who follow a star to Jerusalem

where they ask Herod if he knows the whereabouts of the child they seek.

Herod consults with the priests and scribes in the Temple, who inform him that,

according to prophecy, the messiah is to be born in Bethlehem (Matt 2:5-6).

Because the wise men approach Herod asking,

"Where is he who has been born king of the Jews?",

Herod deceptively sends them to Bethlehem with

instructions to report back to him so that he too could come and worship the

child, when, in fact, his real intention was to locate Jesus and kill him. The star now

reappeared and led the three men to Bethlehem,

"till it came to rest over the place where the child was"

(Matt 2:9). Later, being warned in a dream --one of

five dream warnings in Matthew's infancy narrative (and only in Mathew's

gospel)-- the magi return home without notifying Herod. This then sets the

stage for Herod's slaughter of all the male children under two years of age in

Bethlehem. One obvious question, of course, is why a divinely guided star

did not just lead the magi directly to Bethlehem in the first place. There would have been no need

to make an unnecessary stop in Jerusalem, except to create a slaughter of

infants scenario that replicated the one associated with the birth of Moses in

Exodus. Also, such a highly visible star would have been seen by the

entire populace over a wide region and, indeed, could easily have been followed

by Herod himself and his soldiers. He would, therefore, have had no need of the

magi letting him know the whereabouts of the child. Furthermore, since

Herod had established what many scholars today refer to as a "police state,"

with both an extensive military and a large network of spies, he could surely have

discovered the exact location of Jesus without any help from visitors from

distant Persia.

Several individuals over the years have even gone so far

as to try to date the birth of Jesus by linking the Star of Bethlehem followed

by the magi to a specific astronomical event (see Brown 1977: 166ff.; Coates

2008; Viljoen 2008: 852-853). The most prominent links have been to a supernova

(Clarke et al. 1977), a comet (Origen,

Contra Celsium 1.58;

Phipps, 1986) and a planetary conjunction of Jupiter, Saturn and Mars (Rosenberg

1972;

Hughes, 1979; Sinnot 1986; Humphreys 1991).

However, any attempt

to use astronomical data to date the star the wise men followed in order to

determine the date that Jesus was born is fundamentally flawed. In addition

to the problems associated with dating the star by linking it to specific

astronomical events, all such explanations assume the

historicity of the wise men story and, thus, the validity of dating it.

According to Matthew (2:1-11), the star led the magi to Jerusalem, where it

disappeared and later reappeared to lead them not only to Bethlehem, but to the

specific house in which Jesus was born.

Stars, be they individual stars or conjunctions of stars --or for that matter

supernovas and comets-- don't appear and disappear in a matter of hours or days,

or stand still over a specific location, as described by Matthew. Indeed, if

extraterrestrial objects had performed such bizarre behavior, that behavior

would have been so remarkable and extraordinary that there would certainly have

been some recording of it by various ancient sources, including prominent astronomers

and historians of the time. Yet, there is not a single

mention of such an event outside of Matthew's (and to a lesser extent, Luke's)

infancy narrative. It is not mentioned by any Roman or Jewish sources, including

Josephus;

neither is it mentioned even once elsewhere in the entire New Testament. No

serious astronomer today would accept Matthew's story of the star as describing

a credible historical event (see Paffenroth 1993; Viljoen

2008; Adair 2012).

The Star story was simply a literary prop used by Matthew

to associate Jesus' birth with a significant astronomical event, in the

same way that Luke used the census by Caesar Augustus to situate Jesus' birth in

his gospel (see below).

Significant astronomical events were commonly seen as omens in the ancient world and were frequently associated with the

birth or with major events in the life of great men. In the

Aeneid (2.694), for

example, Aeneas follows a star that leads him to the location where Rome is to

be established (Viljoen 2008: 854). Similarly,

the appearance of a comet (likely Haley's Comet) in 44 BC was interpreted at the

time as a sign of the deification of the recently murdered Julius Caesar (Grant

1970: 94). A comet was also believed to have appeared at the birth of Mithridates,

the king of Pontus and Armenia Minor in northern Anatolia [ca.120–63 BCE] (Cicero,

De Divinatione.,

I.23. 47).

The birth of Alexander the Great was also widely believed to have

been accompanied by supernatural phenomena. According to Plutarch,

the

temple of Artemis at Ephesus burned down the day that Alexander was born, and

"all the Magi who were then at Ephesus, looking

upon the temple's disaster as a sign of further disaster, ran about beating

their faces and crying aloud that woe and great calamity for Asia had that day

been born" (Plutarch,

Parallel Lives:

1.6-7). At the same time, Plutarch (ibid. 1.8-9) maintained that Phillip

of Macedonia, Alexander's father, received three messages on the same day, which

together portended great things for Alexander's future:

the first that Parmenio

had conquered the Illyrians in a great battle, the second that his race-horse

had won a victory at the Olympic games, while a third announced the birth of

Alexander. These things delighted him, of course, and the seers raised his

hopes still higher by declaring that the son whose birth coincided with three

victories would be always victorious.

Cicero likewise recalled the burning of the temple at Ephesus

on the day Alexander was born, and was more explicit regarding the divine origin

of Alexander's birth.

Everybody knows

that on the same night in which Olympias was delivered of Alexander the temple

of Diana at Ephesus was burned, and that the magi began to cry out as day was

breaking: 'Asia's deadly curse was born last night.

(Cicero, De Divinatione:

1.23.47)

Caesar Augustus' birth was likewise attributed to

supernatural causes. His mother, Atia, was believed to have experienced a divine

conception with Apollo.

When Atia had come in the

middle of the night to the solemn service of Apollo, she had her litter set down

in the temple and fell asleep, while the rest of the matrons also slept. On a

sudden a serpent

glided up to her and shortly went away. When she awoke, she purified herself,

as if after the embraces of her husband, and at once there appeared on her body

a mark in colours like a serpent, and she could never get rid of it; so that

presently she ceased

ever to go to the public baths. In the tenth month after that Augustus was born

and was therefore regarded as the son of Apollo. Atia too, before she gave him

birth, dreamed that her vitals were borne up to the stars and spread over the

whole extent of land and sea, while Octavius dreamed that the sun rose from

Atia's womb. (Seutonius,

Lives

of the Caesars

1.94.4)

Three different

sources also claim that Plato (c. 427-348 BCE), the great classical philosopher, was

born of a virgin birth: Speusippus' Plato's

Funeral Oration; Clearchus'

Encomium on Plato; and

Anaxilaides' On Philosophers.

According to these sources, Plato's birth resulted from an immaculate union

between Apollo and his mother Perictione, a vestal virgin. The similarity of

this story with that of Joseph and Mary as told by Matthew is striking. Just as

an angel in Matthew's story appeared to Joseph in a dream, Apollo subsequently

appeared in a dream to Perictione's betrothed husband (Plato's reputed father),

Ariston, who, like Joseph, had no intercourse with his wife until the birth of

her child. Significantly, the story of Plato's miraculous birth did not emerge

decades later, but was told by Speusippus, Plato's own nephew (Enslin 1940:327).

Brown

(1977: 117) suggests that Matthew --ever vigilant to link Jesus' life to

Israel-- may have gained inspiration for his magi/star story from the

story of Balaam (Numbers 22-24). Balaam was a magician (magi)

"from the east" who was summoned by Balak,

"overcome with fear of the people of Israel."

to predict the outcome of pending conflict between Israel and Moab. Balaam, in

his Fourth Oracle pronounced that "a star shall

come out of Jacob, and a scepter shall rise

out of Israel; it shall crush

the forehead of Moab and break down all the sons of Sheth"

(Numbers 24:17). The highly influential Rabbi Akiva, later applied the "Star

out of Jacob" verse to Simon Bar Kosiba, the messianic leader of the final

Jewish revolt against Rome (132-135 CE), after which he was called Bar Kokhba,

which means "star".

If we are going to accept the validity of Matthew's "star story," then we

must also

accept the validity of both the "wise men" and "slaughter of innocents" stories

to which it is intimately connected, as well as the validity of the many other stories

involving the escape of great men from death at birth and the connection

expressed between astronomical

and human events throughout the ancient world. It is for this reason that all attempts to date the

birth of Jesus by determining what may have been "the star" or when

such an astronomical event may have occurred are illusory.

If we

want to find the origin of Matthew's tale of Herod's mass murder of children, we need to look not to the

first-century history of

Judea, but to the stories of the Old Testament, which Matthew borrowed and

applied to Jesus incessantly, as well as to the legends of such births that

circulated throughout the ancient world.19 Matthew's story of an evil

King Herod killing the male children of Bethlehem in order to protect his

reign in Judea is simply the reapplication of the Old Testament story of an evil

Pharaoh slaughtering all the male children of the Israelites in order to protect

his rule in Egypt (Exodus 2:1-10).20

The structure of the two stories is remarkably similar (see Brown 1977: 113).

Furthermore, the Slaughter of Innocents story and the subsequent flight to and

return from Egypt --"Out of

Egypt have I called my son." (Matt 2:15)-- was but one of many stories in which

Jesus' life parallels that of Moses. Others include Jesus presenting the 8

Beatitudes in his Sermon on the Mount (Matt 5:1-11), just as Moses brought his

10 commandments down from Mount Sinai (Exodus 20:1-17); Jesus fasting for 40

days and 40 nights in the desert (Matt 4:1-2) just as Moses did not

eat or drink for 40 days and 40 nights while on the mountain (Exodus 34:28); and

Jesus choosing 12 disciples (Matt:1-4) just as Moses chose 12 leaders of the 12

tribes (Numbers 13:2-3). Significantly, Matthew 2:20 even paraphrases

Exodus 4:19 almost exactly when God commands Joseph to return from Egypt to

Israel.21

But when Herod died, behold, an angel of the Lord

appeared in a dream to Joseph in Egypt, saying, "Rise, take the child and his

mother, and go to the land of Israel, for those who sought the child’s life are

dead." (Matt 2:19-20)

And the Lord

said to Moses in Mid′ian, "Go back to Egypt; for all the men who were seeking

your life are dead." (Exodus 4:19)

The magi, star and slaughter of the innocents

stories are simply props in Matthew's theologically driven infancy narrative.

They cannot be accepted as historical.

%20Byzantine%20Mosaic.jpg)

The Census of Quirinius

(Byzantine mosaic, ca. 1315)

Luke's Census

To

add to the confusion presented by the two infancy narratives, Matthew's story of

Jesus' birth during the reign of Herod stands in direct contradiction to Luke's

claim that Jesus was born during the census called by Caesar Augustus and

administrated by Quirinius, Governor of Syria. According to Luke,

In

those days a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be

enrolled. This was the first enrollment, when Quirinius was governor of Syria.

And all went to be enrolled, each to his own city. And Joseph also went up from

Galilee, from the city of Nazareth, to Judea, to the city of David,22

which is

called Bethlehem, because he was of the house and lineage of David, to be

enrolled with Mary, his betrothed, who was with child. And while they were

there, the time came for her to be delivered. And she gave birth to her

first-born son and wrapped him in swaddling cloths, and laid him in a manger,

because there was no place for them in the inn.

(Luke 2:1-7)

Luke's account of the census at the time of Jesus' birth contains several

fundamental problems. To begin with, apart from Luke, there is not a single

reference anywhere in the historical record to a census encompassing the entire

Roman Empire (i.e., "all the world")

during the reign of Augustus, or, for that matter, of any other Roman emperor.

Indeed, as Gier (1987:145) states, "The Romans kept extremely detailed records

of such events. Not only is Luke's census not in these records, it goes against

all that we know of Roman economic history."

Censuses

were undertaken by Rome primarily for the purpose of collecting taxes. The

two most common taxes collected by Rome were a poll tax (tributum

capitis) and a tax on agricultural produce (tributum

soli) (Schurer 1891:401).23

Given the distinct legal statuses of the various provinces and client kingdoms

that made up the empire, a universal census would have been both useless and

irrelevant. Rome only conducted a census of those territories that were under

its direct rule. Territories, such as Judea, which were under the rule of a

client king, paid a fixed annual tribute to Rome and provided soldiers to

support Roman military ventures under local military command. Both of these

provisions were part of the treaty arrangements that existed between the Roman

Empire and its vassal states. Rome would, therefore, have had no reason to

census these regions and, indeed, such an action would have been considered a

serious treaty violation. There were three censuses of

Roman citizens during Augustus' reign: in 28

and 8 BCE and in 13-14 CE (Brown 1977:549), but not one Roman census of the

territory of a client state.

Herod

maintained a formidable army and police force and undertook extensive building

projects, including building the port city of Caesarea and reconstructing of the

Great Temple in Jerusalem. These expenses, combined with the costs of

administering his kingdom and the payment of tribute to Rome, required the

collection of considerable taxes (see Zeitlin 1967: 96-98; Horsley 1995:

137-144; 216-221). In addition to

continuing to collect the taxes introduced by the Hasmonean rulers he had

overthrown, Herod instituted new taxes, including a poll tax that everyone (male

and female) had to pay. There was also a tributary tax and a tax on the land

(one-third of the seed and one-half of the harvest). He also collected a tax on

houses and real estate, as well as a purchase tax paid by both the buyer and

seller in a transaction. Caravans passing through Judea had to pay an import and

export tax at its borders. Herod also established an office for collecting

revenue at the newly constructed port of Caesarea, and collected rents from

colonists he settled on land within his kingdom. It is estimated that Herod's

subjects paid close to 40% of their income to him in taxes in one

form or another.

In order to calculate what revenues to collect, Herod conducted periodic

censuses, which were vehemently disliked by the populace. There was, therefore,

no need for Rome to conduct a census; Rome simply collected tribute from Herod,

who was responsible for his own finances. According to Zeitlin (ibid.:

99),

The Romans did not

interfere in the internal affairs of Judea during his reign. No accounting was

asked of him with regard to income and expenditures. He had absolute power over

the life and death of his subjects. It would have been inconceivable in such

circumstances for Rome to have required a census of Judea, to say nothing of

being a direct insult to Herod.

The

second issue is the date of the census. The very fact that Quirinius conducted

the census demonstrates that it could not have been undertaken while Herod was

king of Judea, because Quirinius was not the Governor of Syria when Herod was

still alive. Herod died in 4 BCE, but Quirinius did not become Governor of Syria

until 6 CE, a full 10 years later. From 10/9 BCE to 7/6 BCE the governor of

Syria was Sentius Saturninus, and from 7/6 BCE to 4 BCE it was Quinctilius Varus

(Schurer 1891: 405-406).

As

long as Herod was in power and fulfilled his treaty obligations, there was no

need for Rome to conduct a census. However, following the death of Herod, Rome

divided his kingdom among his three sons. Archelaus was given Judea and Samaria;

Antipas was given Galilee and Perea; and Phillip was made tetrarch of Iturea and

Trachonitis, the most northeastern portion of his father's kingdom. From Rome's

perspective, the latter two sons maintained effective administrations. Archelaus,

on the other hand, did not. Continuous mismanagement and political instability

led Rome to remove Archelaus and administer his territories directly. Rome did

this in 6 CE. In the process of establishing direct administration over the two

territories formerly ruled by Archelaus. Augustus commanded Quirinius, the

Governor of Syria, to undertake a census of Judea and Samaria, which were placed

under his command. It makes sense that Rome's census would have been conducted

in 6-7 CE, as this marked both the beginning of direct Roman Rule and Quirinius'

tenure as legate of Syria. Quirinius would have needed to conduct a census upon

assuming office in order to assess the economic resources of the region under

his control so as to determine what revenues he could collect as taxes to

remit to Rome and to fund his new administration.

Some

have tried to argue that the census occurred during Herod's rule.24

However, in addition to the inappropriateness of such a census, as just

mentioned, there is no evidence of a census conducted by Rome while Herod was

still alive. Josephus makes no mention of a Roman census conducted anywhere in

Palestine during Herod's rule and, in fact, clearly refers to the census of 6/7

CE as something new and unprecedented (

Antiquities

18.1.1).

Josephus discusses the census of 6/7 CE in considerable detail, including the

extensive revolt that it precipitated. Judas of Galilee25

led a major uprising in response to the census of 6/7,

becoming by some accounts the founder of the nationalist

Zealot movement (see

Brandon 1967; Brown 1977:552). This revolt is even recorded by Luke in Acts.

Judas the Galilean rose up

at the time of the census and got people to follow him; he also perished, and

all who followed him were scattered.

(Acts 5:37)

Given

that both the death of Herod and the census of 6/7 CE provoked violent

uprisings, which were described in detail by Josephus, an earlier Roman census,

had it occurred, would also have produced a violent response. Yet, not a single

mention exists of such an uprising by Josephus or anyone else. Schurer

(1891:418-419) notes the significance of this lack of evidence.

On no other period is

Josephus so well informed, on none is he so thorough, as on that of Herod's last

years. It is almost inconceivable that he would have ignored a measure such as a

Roman census of that time, which would have offended the people to the quick,

whilst faithfully describing the census of A.D. 6/7, which occurred in a period

of which he reports very much less.

Finally, there is the issue of Joseph taking his family from Galilee to

Bethlehem in order to be counted in the census. There are several problems with

this claim. First, as already indicated, the census included only Judea and

Samaria, the territories formerly ruled by Archelaus. No one from Galilee would

have been included in this census, as the census was conducted in order to

determine the tax base for the two new Roman provinces only. Living in the

territory ruled by Herod Antipas, which is where he would have paid his taxes,

Joseph would have had no reason to leave his place of residence and travel to

the new Roman province of Judea to be counted in a census that had nothing to do

with him. In a Roman census, landed property had to be registered for taxation

within the locality in which it was situated. The person to be taxed had to

register in the place where he lived, or in the chief town of his taxation

district. Luke's report that Joseph traveled to Bethlehem because he was of the

house of David implies that the taxation lists were made according to tribes,

genealogies and families, which was never Roman policy (Schurer 1891:411; Gier

1987:146-147).

Conducting a census based on genealogical descent would not only have been

completely irrelevant for the purposes of collecting taxes, it would have

constituted a bureaucratic and security nightmare. It is doubtful, first of all,

whether a registration based on tribes and genealogies was even possible, given

that many individuals were not necessarily able to establish which ancestral

family they belonged to or where their ancestors lived. Furthermore, David,

Joseph's purported ancestor,26

lived in Bethlehem nearly a thousand years earlier. This would have had

absolutely no importance to the Romans.

Given

that tens of thousands of Jews were at this time living throughout the Roman

Empire, it would have been absurd for Rome to require that they all return to

Palestine, carrying everything they owned, in order to have their property

assessed (Gier 1987:147). Tens of thousands of people would have had to travel

as much as 3,000 miles from such distant lands as Roman Gaul (France today) and

North Africa to reach Palestine in order to be counted in Luke's census. This would have

created an unimaginable flood of people into the region searching for food and

lodging. This, in turn, would have created a demand for food and lodging far

beyond the availability of local resources, producing skyrocketing food prices

and a prohibitive increase in the cost of lodging. This situation would likely

have led to violent protests by the local population, and even to open

rebellion, which could easily have overwhelmed local governments in Palestine.

Such

massive migrations would also have imposed serious hardships on individual

families and caused significant problems for the communities the migrants left.

A journey of 2,000 mile or more in those days would have required people to be away from

their homes for nearly 6 months. Most of these people would not have been able

to afford such an expense, or to forego their source of livelihood for so

long, to say nothing about protecting the homes and belongings that they would

have had to leave behind. Also, many of the economic and social functions the

migrants performed in their local economies would have been interrupted,

inflicting damage on those communities. Furthermore, if, as Luke suggests,

pregnant women were also required to participate in the count, then the number

of women giving birth in the midst of such an arduous journey would clearly have

yielded a sharp increase in maternal and infant mortality over what would have

occurred under the normal circumstances of childbirth. This too would have

engendered hostility towards Rome.

And,

of course, the above discussion applies only to Jews returning to Palestine. If,

as Luke states, Rome required "all the world" to participate in the census, then the conditions

described above would have applied to millions of people distributed throughout

the largest empire in the ancient world. The scale of the social, economic and

political turmoil such a census would have generated is unimaginable --and

absolutely irrelevant to the purpose of a census. Imagine if, given that nearly all Americans are immigrants or descended from immigrants, the U.S.

Government required all of its citizens to travel to their or their various

ancestors' point of immigration into the country to be counted in a

national census. Then imagine that the journey had to be undertaken without the

aid of modern transportation. Such a census would make as much sense as the

census described by Luke. Having considered the incredible social,

political, economic and personal turmoil that such a census would have imposed

throughout the entire Roman Empire, then

imagine that "no other ancient

author considered it important enough to mention, even in passing!" (Ehrman

1997: 102).

Indescribable chaos would have prevailed if everyone throughout the Roman Empire

were required to return to the homes of their ancestors in order to be censused.

Which ancestors'

residence would they choose; those that lived 100 years ago? 200 years ago? 500

years ago? 1000 years ago? It would be absurd, for example, to require the many

thousands of descendants of David, who purportedly lived some ten centuries

earlier, to return to David's birthplace.27

If such a census had been conducted, millions of people would have been

undertaking a migration of unimaginable scope. Just feeding and housing all of

these people, to say nothing about maintaining law and order, would have been a

nightmare beyond the capability of any political authority. As Guignebert

(1935:101; quoted in Gier 1987:147) noted many years ago,

The moving about of men

and families which this reckless decree must have caused throughout the whole of

the Empire is almost beyond imagination, and one cannot help wondering what

advantage there could be for the Roman state in this return, for a single day,

of so many scattered individuals, not to the places of their birth, but to the

original homes of their ancestors. For it is to be remembered that those of

royal descent were not the only ones affected by this fantastic ordinance, and

many a poor man must have been hard put to it to discover the cradle of his

race.

For

such obvious reasons, no example exists of Rome (or of any other government)

having people return to their ancestral homeland for purposes of being counted.

No government in the history of the world would, or ever has, conducted such an

illogical census as the one described by Luke. Collecting taxes depends on where individuals currently

reside, not where their families originated. Requiring individuals to return to

their ancestral home defeats the

whole purpose of a census, which is to enumerate people living in a specific

territory or political entity for the purposes of collecting taxes in that

territory. Roman records indicate that property taxes were collected on site by

traveling assessors (Gier 1987:145), making taxpayer travel completely

unnecessary and counterproductive. There would also have been no reason to

require that Joseph leave Nazareth (in Galilee) where he and his family lived

(Luke 2:39) and travel to Bethlehem (in Judea) to be counted, since he neither

earned money in Bethlehem nor owned property there that could be taxed. Indeed,

in Luke's narrative Joseph and his family had no place to stay when they arrived

in Bethlehem,28

a clear indication that he owned no property there. This is why Mary was forced

to give birth to Jesus in a stable.

And she gave birth to her

first-born son and wrapped him in swaddling cloths, and laid him in a manger,

because there was no place for them in the inn.

(Luke 2:7)

It is

also highly problematic that Luke implies that Mary was obliged to travel with

Joseph for the census. This would not have been the case in a Roman

census. For although women were liable to a poll tax, there is no evidence that

they were required to appear personally. Based on other Roman censuses, whatever

information was needed was simply supplied to local authorities by the head of

the family (Schurer 1891: 412).

Furthermore, if Christians accept December 25th as Jesus' birth date,29

then that means that all of these people --including pregnant women-- would have

been undertaking this unnecessary travel in the dead of winter! (see photos

below).30

Given that the very existence of a census generated violent resistance, forcing

families to travel over long distances in the middle of winter would have made

the resistance even greater than it already was. Throughout their history, Jews

had rebelled for far smaller reasons. Had the Romans tried to implement such an

absurd census in the middle of winter, they would have had a serious military

rebellion to contend with, rather than simply the scattered resistance they did

have to face. It would have required far more than the two Roman Legions (ca.

12,000 soldiers) that Varus brought into Judea to quell the rebellion following

the death of Herod.

|

|

|

Bethlehem in December 2015

Jerusalem

in January 2013

A

census of the type claimed by Luke would also have created a serious security

issue for Rome. Given the intense and violent resistance that a Roman census and

the collection of Roman taxes generated among the Jewish populace, Rome would

never have included the additional requirement that individuals travel for

purposes of the census. It would have made no sense to have so many people

traveling the roads in a territory in which Rome was experiencing open

rebellion.31 In addition to seriously aggravating the hostility and violent

resistance to the census, forced travel would have provided excellent cover for

the various revolutionary groups opposed to the census and to Roman rule (see

Brandon 1967; Horsley 1979; Horsley and Hanson 1995)

to organize and carry out their resistance. The chaos and hostility that would

have accompanied the census would also have been an excellent opportunity for

Rome's enemies (e.g., the Parthians) to attack it. Such a census would,

therefore, have created a security nightmare for Roman

authorities.

Every

aspect of the nativity story as described by Luke is, thus, just as illogical and

without historical foundation as that presented by Matthew. Both are complete

fictions. Luke followed a different chronology from Matthew (2:1), but asserted

a comparable historical absurdity. For Luke, the census was a major historical

event that could provide the illusion of historical accuracy (verisimilitude),

just as Herod's known paranoia provided an advantageous foundation for Matthew's

nativity story. Luke knew that early in the first century CE a census

took place in Judea under Quirinius, and he used it to account for why Joseph

and Mary were in Bethlehem when Jesus was born. However, he places the census

some ten to twelve years too early. That Luke clearly had in mind the census of

Quirinius, and was aware only of that one census, is confirmed by Acts

5:37 quoted above, where he refers to it simply as

"the census," implying

that there was no other census. Significantly, he expresses no link between the

census he refers to in Acts and and the one he associates with the birth

of Jesus.

Luke Was Not A Reliable Historian

Luke's writings contain enough internal inconsistencies regarding events

surrounding the birth of Jesus that his birth narrative cannot be considered

historically credible. As just noted, Luke mentions the census of Quirinius in

Acts (5:37), but does not link it at all to the birth of Jesus. In fact,

in Acts 5:37, Luke incorrectly places the insurrection of Judas the

Galilean (caused by the census of Quirinius in 6-7 A.D.) after the insurrection

of Theudas (Acts 5:36). However, Theudas' insurrection occurred in 44-46

CE, some 40 years after the census (Josephus, Antiquities 20.5.1; see

also Schurer 1891: 426-427; Zeitlin 1967: 201-202, 208-209, 304; Horsley and

Hanson 1965:164-165). By

placing the census and the revolt under Judas of Galilee after the messianic

revolt of Theudas, Luke not only gets his facts wrong; he clearly implies that

"the census,"

as he referred to it, occurred long after Jesus' death and, therefore, could not

possibly have been associated with Jesus' birth. Thus, Luke's elaborate

discussion of the census in his infancy narrative flatly contradicts his

reference to the same census in Acts (Brown 1977:553).

For before these days

Theu′das arose, giving himself out to be somebody, and a number of men,

about four hundred, joined him; but he was slain and all who followed him were

dispersed and came to nothing. After him Judas the Galilean arose in the days of

the census and drew away some of the people after him; he also perished, and all

who followed him were scattered. (Acts 5: 36-37)

Furthermore, the chronological information presented by Luke in Chapter 2

directly contradicts the information given by him in Chapters 1 & 3.

In the days of Herod, king

of Judea, there was a priest named Zechari′ah, of the division of Abi′jah;

and he had a wife of the daughters of Aaron, and her name was Elizabeth. And

they were both righteous before God, walking in all the commandments and

ordinances of the Lord blameless. But they had no child, because Elizabeth was

barren, and both were advanced in years. (Luke 1: 5-7)

And behold, your [Mary's]

kinswoman Elizabeth in her old age has also conceived a son; and this is the

sixth month with her who was called barren. (Luke 1: 36)

In the fifteenth year of

the reign of Tiberius Caesar . . . the word of God came to John

the son of Zechari′ah in the wilderness; and he went into all the region about

the Jordan, preaching a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins. . . .

Jesus, when he began his ministry, was about thirty years of age, . . .

(Luke 3: 1-3, 23)

Luke

(1:5) states that the annunciation of John the Baptist occurred

"in the days of Herod, king of Judea."

Luke (1:36) then states that Mary's pregnancy began about six months after

Elizabeth's pregnancy had begun, meaning that Jesus would have been born some

15-16 months after the annunciation of John the Baptist's birth. This would

place Jesus' birth no later than 3 BCE (Brown 1977: 547). Similarly, Luke (3:23)

indicates that Jesus was 30 years old in the 15th year of Tiberius'

reign (27-28 CE). This would also place Jesus' birth in the 3-2 BCE time period.

However, this was 10 years before Quirinius became governor of Syria and

conducted the census described by Luke in Chapter 2, and some 40 years before

the same census referred to by Luke in Acts (5:37). Luke clearly cannot

be trusted to place events in their correct historical time period.

Inasmuch as Luke shows himself to be both inaccurate and contradictory regarding

the events surrounding this census, Brown (1977: 423) suggests, "the

use of the census to explain the presence of Joseph and Mary in Bethlehem is a

Lucan device based on a confused memory

(emphasis added)." Haenchen (1966: 260) maintains instead, "The fact that Luke

can present the same event so completely differently shows the astonishing

liberty this author takes." Several examples support Haenchen's conclusion over

that of Brown: that Luke manipulated his facts to conform to his beliefs, rather

than that he simply made some honest mistakes. For example, in the closing

verses of the Third Gospel (Luke, Chapter 24), Luke clearly implies that Jesus

ascended into heaven on the very day of his resurrection, whereas in the opening

verses of Acts (1:3) he states explicitly that the ascension occurred 40

days later.

In the first

book, O Theoph′ilus, I have dealt with all that Jesus began to do and

teach, until the day when he was taken up, after he had given commandment

through the Holy Spirit to the apostles whom he had chosen. To them he presented

himself alive after his passion by many proofs, appearing to them during forty

days, and speaking of the kingdom of God. (Acts 1:1-3)32

Luke's lack of reliability as a historian is also illustrated by the three

reports of Paul's conversion that he presents in different chapters in Acts

(Chapters 9, 22 & 26) where the same event is described differently in each

case. In other words, Luke adjusted his facts to fit the context in which he was

placing them and, likely, the audience he was addressing. In addition,

the message of the story becomes more elaborate as it is retold. In Acts

(9:5-6), the heavenly voice says, "I

am Jesus, whom you are persecuting; but rise and enter the city, and you will be

told what you are to do," In Acts

(22:8) the voice simply says, "I am Jesus of

Nazareth whom you are persecuting," though

Jesus identifies himself as "Jesus of Nazareth."

However, in Acts (26:15-18), the heavenly

voice says considerably more.

I am Jesus whom you are

persecuting. But rise and stand upon your feet; for I have appeared to you for

this purpose, to appoint you to serve and bear witness to the things in which

you have seen me and to those in which I will appear to you, delivering you from

the people and from the Gentiles --to whom I send you to open their eyes, that

they may turn from darkness to light and from the power of Satan to God, that

they may receive forgiveness of sins and a place among those who are sanctified

by faith in me.

Also,

whereas in Acts (9:7) Paul says "The men

who were traveling with him stood speechless, hearing the voice but seeing no

one," in Acts (22:9), Luke has Paul say

the exact opposite, "Now those who were with me

saw the light but did not hear the voice of the one who was speaking to me."

Such discrepancies are important for determining the historical value of Acts

and, for that matter, of any of Luke's writings, including his description of

Jesus' birth. As Haenchen (1966: 260) aptly expresses it,

The author is not so much a

historian in our sense of the word as he is a fascinating narrator. He writes

not for a learned public, which would keep track of all his references and

critically compare them, but rather for a more or less nonliterary congregation

which he wants to captivate and edify.

For this purpose he uses a

peculiar technique: he joins short, compact, picturesque scenes together like

the stones of a mosaic.

Luke's writings were directed not only to local Christian congregations, but, as

indicated by the opening verses of both Luke's Gospel and Acts, to Graeco-Romans

who may or may not have been part of the Christian community. Luke's writings,

therefore, incorporate Hellenistic ideas and concepts far removed from the Jewish

Palestinian context in which Jesus and his apostles lived and preached. For

example, the climax in the apostle's dispute with the High Council given in

Acts 4:19 and 5:29 echo the words of Socrates borrowed from Plato's

Apology

(29 D): "I

shall, then, obey God rather than you" (Haenchen

1966: 262). Also reflecting Luke's Greek orientation is the fact that of all the

sermons given by Paul to Gentiles, the only one mentioned in Acts (other

than a few sentences spoken in Lystra (Acts 14:15-17), is given in

Athens, the center of Greek culture, which was peripheral to Paul's mission (Dibelius

1956:154-155). Athens provides the appropriate setting for a sermon in which

Paul applies Greek ideas (ibid.). In commenting on the veracity of

Acts' description of Paul's speech in Athens, Dibelius (ibid.: 155)

concludes:

All questions as to whether Paul really made such a speech, and whether he

made it in Athens, must be waived if we are to understand Luke. He is not

concerned with portraying an event that happened once in history, and which had

no particular success; he is concerned with a typical exposition, which is in

that sense historical, and perhaps more real in his own day than in the

apostle's day. He follows the great tradition of historical writing in antiquity

in that he freely fixes the occasion of the speech and fashions its content

himself.

Luke

also tried to minimize differences among Christians in Acts in order to show a united

development of Christianity against hostile outside forces. He conceived

missionary development as beginning in Jerusalem among Jews only, then spreading

to Samaria (Samaritans were no longer Jews but not yet Gentiles), and

finally "to the end of the earth,"

presumably to Rome. Luke wanted to present this as a continuing smooth process,

all part of God's design. However, in doing this, he again contradicts himself.

In Acts (9:31) he states that the Churches in Judaea, Galilee, and

Samaria were enjoying peace again, whereas in (11:19) he says that

"those who were scattered because of the persecution of

Stephen were still fugitives, wandering as far as Phoenicia, Cyprus, and

Antioch" (Haenchen 1966:263).

Similarly, the conflict between Paul and the Jerusalem

Church, including his break with Peter (Galatians 2:11-21), is discussed

explicitly by Paul, but largely ignored in Acts (cf. Ch. 15).

Luke

labors to present the growth of Christianity as a unified, divinely guided

journey rather than as a result of an itinerant mission based on fortuitous

human choices. Dibelius (1956: 129-130, 148-149), for example, shows how Luke

presented an edited version of Paul's travels to Macedonia and Greece in order

to make Paul's travels fit that image. The result is that Luke's descriptions of

events frequently do not agree with those presented by Paul himself. In

describing Paul's travels to Macedonia and Greece, Luke (Acts 16: 6-10) abbreviates

Paul's journey considerably and presents Paul's itinerary, not as a product of

decisions made by Paul, but as a journey thrice directed by divine intervention:

once by an appearance of the "Holy Spirit";

once by the "Spirit of Jesus"

and once by a nocturnal vision of a man from Macedonia.

None of these visions, however, are mentioned by Paul. In addition, Luke

provides few details about Paul's movement and activities during this trip. "We

read no names of stations or of persons. The type of information which, in other

parts of the book, Luke has taken from the itinerary, is missing here."

(Dibelius 1956:129)33

And they went through the

region of Phry′gia and Galatia, having been forbidden by the Holy Spirit to

speak the word in Asia. And when they had come opposite My′sia, they attempted

to go into Bithyn′ia, but the Spirit of Jesus did not allow them; so, passing by

My′sia, they went down to Tro′as. And a vision appeared to Paul in the night: a

man of Macedo′nia was standing beseeching him and saying, 'Come over to Macedo′nia

and help us.' And when he had seen the vision, immediately we sought to go on

into Macedo′nia, concluding that God had called us to preach the gospel to

them.

(Acts 16: 6-10)

Dibelius (1956:148, note 25) claims that "the text of Acts had much more

drastic revision than that of any other book of the New Testament." Acts was

not accepted into the canon of Christian writings until much later than Luke's

gospel, not until around 180 CE. Dibelius argues that this allowed more time for

it to undergo modification before it came under canonical control.

[Acts] . . . was exposed to the typically varied

fate of a literary text. Proof for all this is precisely the fact of redaction,

which is known to us from the witnesses of the Western text. Thus the fact

must be taken into consideration that during this early period . . . changes . .

. were made in the text of Acts, and that no traces of the authentic text at

certain points are preserved in any single manuscript.

(Dibelius 1956: 89-90)34

There is

also the issue of the so-called

"We Passages" (see Acts 16:10-17;

20:5-15; 21:1-18; 27:1-28:16) in which the author of Acts presents first-person

plural (i.e., he and Paul together) travel narratives in order to present

himself as a travel companion to Paul and as an eyewitness to some of the events

that took place. Several scholars have questioned the authenticity of those

passages (cf. Brown 1977: 236; Ehrman 2013:265-282). All of the passages demonstrate a rather abrupt

beginning and end and are immediately preceded and followed by third-person

descriptions of events that contain no involvement of the author, suggesting

that they were inserted into a pre-existing text. The use of the first-person

narrative was a common technique employed in ancient writings, including

numerous early Christian documents (see Ehrman 2013: 270-274), in order to enhance

the authority of an author's statements.

It

may be confidently stated, then, that Luke was not a reliable historian and that his

descriptions of historical events cannot be trusted. Doughty (1997), in

an extensive comparison of Paul's letters and Luke's description of the same

events in Acts (cf., Acts 9:19-29 vs. Galatians 1:16-17), describes Luke's writing as "Apologetic Historicizing." Given, therefore, the repeated

contradictions in Luke's writings, combined with all of the improbabilities

associated with Luke's census, there is no reason to give his story of the

census and its role in having Jesus born in Bethlehem any credibility.

* *

* * *

In

summation, then, it may be explicitly stated that both Matthew's and Luke's

nativity stories were theologically derived,

rather than historically based. Just as there is not a single reference in

either Christian or non-Christian sources to Herod's slaughter of innocent

children, other than that by Matthew, so also is there no mention of a Roman

census that would have involved Jesus' family, other than that by Luke. In other

words, not a single piece of credible historical evidence exists that connects

Jesus' birth to either of these purported events. In addition, both "events," as

they are described in the two gospels, contain elements that are clearly

illogical. Both "events" merely served as props upon which Matthew and

Luke constructed their respective nativity stories. They were used to provide

the stories with verisimilitude by investing them with an air of historicity.

The census story was introduced by Luke as a literary device to have Jesus born

in Bethlehem, while the slaughter of innocents story was created by Matthew as a

vehicle to link Jesus' life to that of Moses. Each

author chose their respective settings for Jesus' birth in order to create a

dramatic context that would enhance their particular theology. For

Matthew, Jesus' escape from Herod's "Slaughter of the Innocents" was a replay of

Moses' escape from the Pharaoh's killing of the first born in Exodus

(1:16-22) and of the Israelites escape from Yahweh's slaughter of

Egyptian children (see Exodus 11-12) in the Hebrew Bible. Luke,

on the other hand, was not as concerned with explicitly linking Jesus to Moses,

as was Matthew; he was more concerned with placing Jesus' birth in the context

of the Gentile Roman world for which he wrote. So, Luke situated Jesus'

birth during the Roman census of Judea. However, Luke made extensive use of Old

Testament birth narratives, in particular those describing the births of Isaac,

Samuel and Samson, in creating his birth story.35

The Old Testament, therefore, served as an important source for both Matthew and

Luke.

The

two infancy narratives depended not only on

canonical readings of Old Testament stories, but also upon popular versions of the

same stories. Winter (1958: 263) summarizes the situation quite well.

[W]e should not overlook the fact that the

O.T. circulated not only in literary form among the learned, but also in

midrashic form for the edification of the unlearned, and that in its oral

tradition it was often embellished and enlarged by popular motifs. The stories

of the birth of Isaac, of Moses, of Samson, of Samuel, and other O.T. heroes

were passed on from mouth to mouth and thus came to be assimilated to each other

in current narratives. Traits from one story were combined with traits from

another. Circumstantial details were added. From time to time these stories were

committed to writing, and all the amplifications that had accumulated around the

canonical accounts were included in popular new versions. The recently

discovered Genesis Apocryphon from Qumran, the Book of Jubilees, the Liber

Antiquitatum by PseudoPhilo, and later Midrashim bear witness to a development

of this kind. It is the way in which popular narratives come to grow together.

The same phenomenon can be observed in our own time, with regard to New

Testament stories. There are children's books retelling the Story of Jesus,

features from Mark and John and Luke and Matthew being all woven together into

one fabric of many colours. Similarly the stories from the Old Testament about

the birth of prominent men were legendarily enlarged so as to produce folklore

for the edification of a Jewish public in ancient Israel. These legends provided

most of the subject matter for the description of Jesus' birth both in Matthew

and Luke. Whilst in Matthew chiefly legends about the birth of Moses served as

the prototype, or model, for describing the birth of the New Moses, in Luke it

is a popular narration of Samson's birth which was utilized firstly in a

description of the birth of John the Baptist and later after being adapted by a

Judeo-Christian redactor came into the hands of the Third Evangelist. He finally

employed it without any significant changes on his part, in the first two

chapters of his gospel.

Thus,

neither Matthew's nor Luke's birth story can be

accepted as a historically reliable description of Jesus' birth or, by extension,

a plausible basis for dating that birth. In the end,

no credible evidence exists that can be used to

determine which year Jesus was actually born. His birth year, therefore, remains a

mystery.

* *

* * *

NOTES

1. Many different calendars were

used throughout the Roman Empire during the early centuries of the Christian

era. The earliest Christians, being converted Jews, would likely have relied on

the Jewish lunar calendar. However, Christianity eventually spread to groups

outside of Palestine that relied on the Roman calendar introduced by Julius

Caesar in 46 BCE (Neville 2000: 6). In that calendar, years were counted from

ab urbe condita ("the founding of the City" [Rome]), with 1 AUC

signifying the year Rome was founded, 10 AUC the 10th year of Rome's

reign, and so on. Citizens of Antioch in Syria established the first year of

their calendar as 49 BCE in commemoration of Julius Caesar's dictatorship. In

the fifth century many Greek-speaking Christians started to number years from

the creation of the world (Anno Mundi), which they believed occurred in

either 5493 or 5509 BCE. By the tenth century CE, Anno Mundi dating

--with the world's creation fixed at 5509 BC-- became standard in the Byzantine

Empire and hence in the Orthodox countries of Eastern Europe (ibid.).

During the fourth century, however, many Christians began situating themselves

within the "Era of the Martyrs," which started in 284 CE, when Diocletian

became emperor and began persecuting Christians. Dionysius' calendar did not

spread very rapidly. Even Dionysius himself did not use his calendric