Mithraism and Christianity

Competition, Exclusion and Appropriation

William Abruzzi

(2019)

Expanding out of Palestine and into the wider Roman world, Christian missionaries as early as Paul himself encountered a wide array of pagan beliefs and practices. However, as the Church became centered in Rome and strove to establish itself as the official religion of the empire, it had to compete with those forms of paganism that predominated in the very heart of the empire and that enjoyed official support. While several gods and their associated beliefs and rituals enjoyed official recognition, worship of the sun god in the form of

Sol Invictus was later superseded during the third century CE by devotion to Mithras. As Christianity spread throughout the empire and became increasingly dominant in Rome itself, Mithraism formed the foundation of Roman paganism. It was, thus, with this religion that the emerging Roman Church had to most directly compete and against which it directed much of its anti-pagan hostility, while at the same time incorporating many of its beliefs and rituals. including placing the celebration of Jesus' virgin birth on December 25th.

One of the most important of the pagan religions to influence Christianity was

Mithraism, the product of a reformation within the ancient Persian religion of Zoroastrianism during the 17th or 18th centuries BCE. Mithra was the last of the official sun gods of the Roman Empire and, particularly in the third century, represented a serious rival to Christianity. It, therefore, experienced considerable hostility from the Church as the latter ascended to become the official religion of the empire.

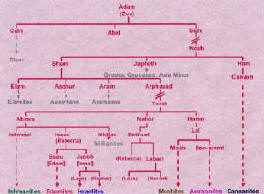

Considerable controversy surrounds specifically how and in what form Mithraism was introduced into the Roman Empire. Proposals may be divided into three groups: (1) those which promote a Persian origin; (2) those which trace its origin to Asia Minor [present-day Turkey]; and (3) those which claim the religion originated in Rome itself (see Beck 1998: 115-116). The traditional view, promoted by Cumont (1903) and accepted by most scholars for several decades, was that Mithraism originated in Persia and spread westward to Rome. According to early Persian mythology, Mithras was born of Anahita, an immaculate virgin mother once worshipped as a fertility goddess and subsequently given the title 'Mother of God' (see Murdock 2013; Cumont 1903).1 Mithras was incarnated into the human form of the "Saviour" expected by Zarathustra. Anahita was believed to have conceived from the seed of Zarathustra preserved in the waters of Lake Hamun in the Persian province of Sistan. Mithra remained celibate throughout his life and ascended to heaven in 208 BCE, 64 years after his birth. Parthian coins and documents bear a double date with this 64-year interval.

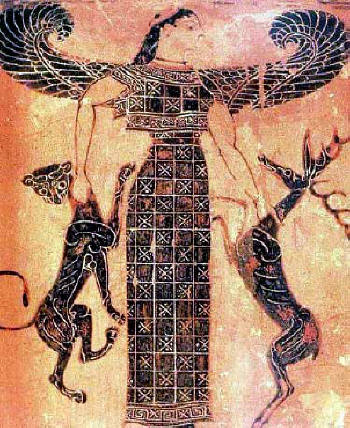

Anahita

"Immaculate Virgin Mother of the Lord Mithras"

Mithraism became the most popular and influential of the many mystery religions2 that existed in the Roman Empire at the time that Christianity began, and was the major religion with which Christianity had to compete during the early centuries of the common era. Its pre-eminence lasted until the late 4th century when Christianity was declared the official religion of the Roman Empire. According to Cumont (ibid.), Mithraism became dispersed geographically with the growth of empire.3 He claimed that the cult of Mithras spread into northern India and into the western provinces of China during the expansion of the Persian Empire in the sixth century BCE and also into the more westerly regions of the Archaemenid [First Iranian] Empire (550-330 BCE), including Asia Minor, Babylon and Armenia (Gnoli 1987: 580). According to this view, the religion evolved and changed as it spread outside of Iran (see Gordon 1972: 96; Lease 1980: 1317; Gnoli 1987: 580). As Mithraism spread from Persia, it became transformed from a loose collection of rites and traditions into a more centralized theology. In the process, Mithras became assimilated with Shamash, the Babylonian god of justice and protection and the sun god from whom King Hammurabi received his code of laws in the 18th century BCE (Cumont 1903). In India, Mitra (The Hindu name for Mithras) was incorporated into the Hindu pantheon of gods. In the Mesopotamian Valley and Asia Minor, Mithra adopted astrological and eschatological elements found in Chaldean and Babylonian religious beliefs (Brandon 1954: 110; Lease 1980: 1310-1311). Eventually, due to Roman imperial expansion eastward, Mithraism became absorbed into the Roman Empire, the Persian (Parthian) Empire's mortal enemy.4 According to the Greek historian Plutarch (46-125 CE), Mithraism was first introduced into Italy by pirates from Cilicia [South-East Turkey]. The Roman historian Quintus Rufus claimed instead that the worship of Mithras spread from Persia to Rome through the Phrygians of central Anatolia.

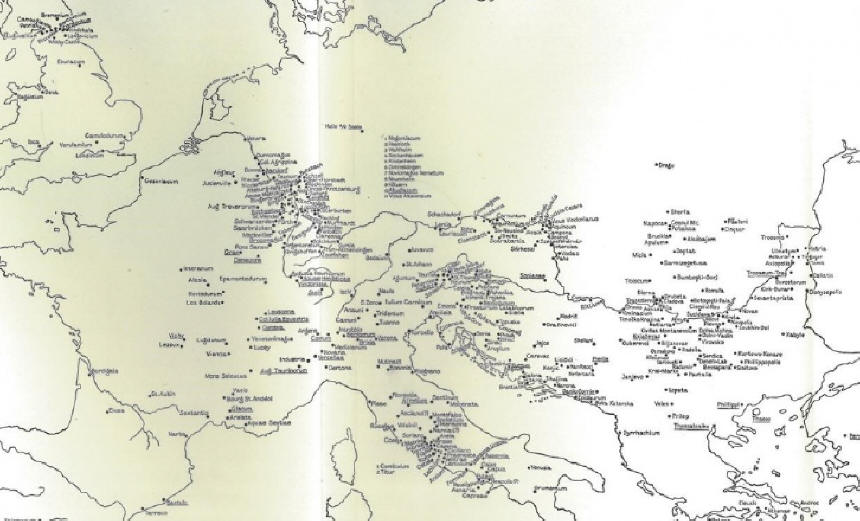

Distribution of Mithraic sites

(Vermaseren 1955)

Cumont's thesis regarding the Iranian origin of Roman Mithraism has come under serious criticism. Several authors have pointed to Asia Minor as the location of Mithraism's birthplace. The earliest reference to Mithras, according to Brandon (1954: 108), can be found in Hittite documents dating to the second millennium BCE

5 where Mithras appears as a god of the Mitanni, an Aryan people who inhabited land extending from southeastern Asia Minor into northern Syria and Iraq [see map below]. In Mitanni sacred literature, Mithras figured prominently (under the name Mitra) as a deity associated with light, especially the light of the sun, and was regarded as "the all-seeing witness of men's deeds" (Brandon 1954: 108). According to Brandon (ibid.), it was later in Persia (Iran) that Mithras acquired his greatest glory and became "a god of universal significance."6 Brandon (1954: 109-110) supports his thesis by stating that the earliest Zoroastrian documents, such as the Gathas of Zarathustra, make no mention of Mithras, who only appears prominently in later documents, such as the Mihir Yasht, where he is assigned an exalted place in the faith and serves as a protector of those in need and as one of the judges in the Final Judgment.7

The Mitanni

In a collection of papers presented at the First International Congress of Mithraic Studies in 1971, John Hinnells (1975) and Richard Gordon (1975) challenged Cumont's position on the Iranian origin of Mithraism. Both accused Cumont of circular reasoning, claiming that he began with the belief that Roman Mithraism developed from Iranian religion, found Iranian parallels to the symbols of Roman Mithraism, and then used these parallels to prove the Iranian foundations for Mithraism (see also Ulansey 1989: 1; Hopfe 1994: 16-17).

An increasing number of authors have since proposed that Asia Minor provided both the origin of Mithraism and the locus of its spread throughout the Roman Empire. Although Ulansey (1989: 125) recognizes, "as the history of Christianity eloquently demonstrates, a religion can become a very different thing hundreds of years and thousands of miles from its time and place of birth," he (ibid.: 8-9) identifies several problems associated with the claim that Roman Mithraism originated in Iran. According to Ulansey, critical features of Roman Mithraism are completely absent from the Iranian worship of Mithras, most notably

1. the hierarchical organization of Roman Mithraism with its associated series of initiations into higher levels of cult organization.

2. the strict secrecy surrounding the group's doctrines.

3. the distinctive cave-like temples (Mithraem) in which meetings were held.

and, most importantly,

4. the central iconography of Roman Mithraism --the tauroctony-- in which Mithras, accompanied by several other celestial figures, is depicted in the act of killing a bull.

Ulansey maintains that none of these essential characteristics of Roman Mithraism was to be found in the Iranian worship of Mithras. The tauroctony formed the central focus of worship throughout Roman Mithraism; yet, as Ulansey (ibid.: 8) emphasizes, "there is no evidence that the Iranian god Mithra ever had anything to do with killing a bull" (see also Shandruk 2004; Kiminski 2008: 9-10).

Expanding on the astronomical interpretations of the Mithraic tauroctony by Insler (1978) and Beck (1977), Ulansey (1989.: 67-76) argues that the cult of Mithras originated among Stoic philosophers in Tarsus [in Cilicia; see map below] who discovered what they believed was astronomical evidence for the existence of a new and more powerful god than was previously recognized --one who controlled the cosmos.8 They identified this god with Perseus, one of the principal [Greek] hero gods of Tarsus, who the philosophers believed dominated the bull (Taurus or Tarsus). Ulansey argues for the metamorphosis of Perseus into Mithras at Tarsus based on the existence of numerous iconographic similarities between the two gods, including the fact that:

1. both Perseus and Mithras were associated with underground caves, (including the belief that Mithras was "born from a rock", the rock being the Persian symbol for heaven (Lease 1980: 1311).

2. both gods were portrayed wearing a Phrygian cap, an ancient symbol identifying the wearer as being of Persian origin;

3. Mithras was placed with a sword above the bull on the tauroctony in the exact same position that the constellation of Perseus [also pictured with a sword] is located above that of Taurus (the bull) in the northern sky;

4. Mithras is always portrayed on a tauroctony as looking away when he kills the bull just as Perseus is always portrayed looking away when he is killing the Gorgon Medusa; and

5. the "remarkable similarity" between the figure of the Gorgon in Greek mythology and that of the Mithraic lion-headed god, Kronos.

Ulansey offers a compelling astronomical explanation for the iconography of the tauroctony. Whereas all of the Zodiacal gods portrayed on the tauroctony existed on or below the ecliptic of the Celestial Equator (c. 4,000-2,000 BCE), the constellation of Perseus existed above it, suggesting that Perseus (Mithras) controls all the other celestial forces (see also Stark 1869; Beck 1978; Insler 1978 for astronomical interpretations of the tauroctony).

. . . the obvious importance of Mithras over against other figures in the tauroctony corresponds exactly to the fact that the constellation of Perseus is above the ecliptic, while all the other constellations reflected in the tauroctony are either on or below the ecliptic. (Ulansey 1989:59).

This new religion became popular with Cilician pirates, who had close ties to the intellectual circles of Tarsus and who were interested in astral religion. They purportedly changed the name of the hero god from Perseus to Mithra in honor of Mithridates VI Eupator, the last of the dynasty of rulers of Pontus that preceded Roman rule of Cilicia. It was, according to Ulansey, this group of pirate-sailors who gave Mithraism its form and who spread the religion to the Roman world, as claimed by Plutarch.

Tarsus in Cilicia

Beck (1998) also argues for an Anatolian origin of Mithraism. However, he proposes a different location than Cilicia, situating the origin of Roman Mithraism in the Commagene Kingdom in eastern Anatolia [see map below]. It is here that the monuments and texts of Antiochus I (87-38 BCE), the founder of a syncretistic Greco-Iranian royal cult, assign Mithras a prominent place in a newly defined pantheon of gods. Beck (1998: 121-122) argues that Mithraism's spread throughout the Roman Empire followed the demise of the Commagene Kingdom in 72 CE when the Emperor Vespasian removed Antiochus IV from his throne and incorporated his territory into Roman Syria. These years witnessed a period of "unusual turmoil and mobility of personnel across the Empire"9 in which Commagenian military elements became engaged in both Roman civil wars and the Judean Revolt in Palestine. According to Beck (1998: 121-125), it was through their intimate contact with the Roman soldiers involved in those conflicts that Commagenian soldiers initiated the spread of Mithraism throughout the Roman Empire.

The Commagene Kingdom

I propose to locate Mithraism's founding group among the dependants, military and civilian, of the dynasty of Commagene as it made the transition from client rulers to Roman aristocrats. The kingdom of Commagene on the Empire's eastern marches with Parthia and Armenia figures, more or less prominently, in all accounts of the transmission of Mithras worship, because the monuments and texts of Antiochus I, its mid-first-century B.C. ruler and the founder of a remarkable syncretistic Greco-Iranian royal cult, accord to Mithras a prominent place in the newly defined pantheon. It is however, on the ending of the kingdom more than a century later that I wish to focus. The actual demise occurred in A.D. 72 with the deposition of the long-reigning Antiochus IV, following a period of unusual turmoil and mobility of personnel across the Empire. Commagenian military elements (under royal command) were engaged in both the Judaean and Civil Wars, and there would have been extensive contact with Roman legionary and other troops (including the units already identified as among the earlier carriers of the new mystery cult: XV Apollinaris, V Macedonica, II Adiutrix). On the civilian side, the dynasty, after its deposition, was resident for a period in Rome: contact between its familia and the familiae of the Roman aristocracy, including the imperial familia, is more than likely. What I propose, then, is that the Mysteries of Mithras were developed within a subset of these Commagenian soldiers and familyretainers and were transmitted by them at various points of contact to their counterparts in the Roman world. Development and transmission should be seen as overlapping, not rigidly sequential, phases: certain of the essentials of the Mysteries will have been in place prior to their transmission, but they were developed into their familiar form in and through the process of transmission itself. (Beck 1998: 121-122)

10

Beck (1998: 117-120) argues that his proposed scenario for the origin of Mithraism satisfies all four "parameters" that he claims must be satisfied before any original group can be identified. These include:

1. "The postulated foundation group should be reasonably close in time to the cult's earliest attested dedications and monuments," which first appear at the end of the first century CE or the beginning of the second;

2. Claims of origin "must be compatible with the transmission of the Mysteries within a comparatively short time span to widely separated parts of the Empire." A major problem in determining the exact origin of Roman Mithraism has been the "simultaneity" of the archaeological record throughout such a large geographic area. This problem is overcome by the early cult's association with Commagene soldiers who became dispersed throughout the empire, claiming at this time that the distinction between Rome and Anatolia constituted a "false dichotomy";

3. The founding group must have been "social 'insiders". It cannot have comprised a marginal or alienated social group; otherwise, it would not have been so readily adopted by successful individuals and by social elites. Most scholars agree that Mithraism appealed primarily to conformists and stress the importance of family and the role of both bureaucratic and military organizations in the propagation of Mithraism (see Beck 1998: 119, note 30);

4. The founding group had to possess both a strong Iranian religious tradition centered on the worship of Mithra and an educated Western tradition in which astrology furnished the master metaphors of cosmology and soteriology, both of which were fundamental to the Mithraic mysteries. These two elements were clearly present in the dynasty of Commagene (70 BCE - 72 CE).

Hopfe (1994; see also Hopfe and Lease 1975) also rejects the Persian origin of the Roman cult of Mithras. maintaining that "the weight of scholarly opinion has clearly moved away from the long-held theory that Mithraism began in Persia and moved westward across Babylon, Syria, Asia Minor, and into Rome" (Hopfe 1994 18). However, Hopfe goes one step further, repudiating the role that Anatolia played in the origin of Roman Mithraism as well. He disparages what he considers the uncritical acceptance of Plutarch's single statement identifying Cilician pirates as the forbearers of Roman Mithraism and argues, instead, that Mithraism originated in Rome itself. Hopfe emphasizes that while hundreds of Mithraea have been found throughout the Roman Empire, the overwhelming majority have been found in central Italy and northern Germany,11 whereas only three have been discovered in Roman Syria: at Dura-Europos on the eastern border of Roman Syria; at Caesarea Maritima on the Mediterranean coast of Roman Palestine; and at Sidon on the Lebanese coast south of Beirut [from which too few remains survive to draw any significant conclusions]. Hopfe further argues that neither the Dura-Europos nor the Caesarea Mithraea support an early Mithraic presence in Roman Syria, i.e., on the eastern margin of the Roman Empire. The Dura-Europos Mithraeum was destroyed and rebuilt several times. Both the structure of the Mithraeum and its artifacts suggest a Roman rather than an Eastern (Persian) origin.12 Similarly, the construction of the Caesarea Mithraeum, dated to the late 3rd and early 4th centuries (ibid.: 8), clearly followed rather than preceded Roman occupation of the region. Significantly, the overlying stratum suggests that it was constructed during the Julian Revival of paganism (361-363 CE). in which Mithraism occupied a prominent position (Hopfe and Lease 1975: 8). Hopfe (1994: 23-24), thus, concludes,

Archaeological evidence of Mithraism in Syria is therefore in marked contrast to the abundance of Mithraea and materials that have been located in the rest of the Roman Empire. Both the frequency and the quality of Mithraic materials are greater in the rest of the empire. Even on the western frontier in Britain, archaeology has produced rich Mithraic materials, such as those found at Walbrook.

If one accepts Cumont's theory that Mithraism began in Iran, moved west through Babylon to Asia Minor, and then to Rome, one would expect that the religion left its traces in those locations. Instead, archaeology indicates that Roman Mithraism had its epicenter in Rome. Wherever its ultimate place of origin may have been, the fully developed religion known as Mithraism seems to have begun in Rome and been carried to Syria by soldiers and merchants. None of the Mithraic materials or temples in Roman Syria except the Commagene sculpture bears any date earlier than the late first or early second century. While little can be proved from silence, it seems that the relative lack of archaeological evidence from Roman Syria would argue against the traditional theories for the origins of Mithraism.

13

Roman Empire

(c. 210 CE)

Whatever the ultimate origin of Mithraism, Roman expansion into Asia Minor appears to have been a significant factor facilitating its introduction into the Roman Empire. Mithraism was early on, and for a long time, intimately associated with the Roman military. According to Cumont (1903),

In 67 BCE the first congregation of Mithras-worshipping soldiers existed in Rome under the command of General Pompey. From 67 to 70 C.E., the legio XV Apollinaris, or Fifteenth Apollonian Legion, took part in suppressing the uprising of the Jews in Palestine. After sacking and burning the Second Temple in Jerusalem and capturing the infamous Ark of the Covenant, this legion accompanied Emperor Titus to Alexandria, where they were joined by new recruits from Cappadocia (Turkey) to replace casualties suffered in their victorious campaigns.

After their transportation to the Danube with the veteran legionnaires, they offered sacrifices to Mithras in a semicircular grotto that they consecrated to him on the banks of the river. Soon, this first temple was no longer adequate and a second one was built adjoining a temple of Jupiter. As a municipality developed alongside the camp and the conversions to Mithraism continued to multiply, a third and much larger Mithraeum was erected towards the beginning of the second century.

Due to its close connection with the Roman military (see Gordon, 1972: 111-112), Mithraism quickly spread throughout the Roman Empire to wherever Roman soldiers were stationed. Over 420 Mithraic sites have been discovered (Clauss 2001:xii).

14 It began its expansion during the first century CE, reached its peak in the third century, and declined in the face of increasing competition from Christianity during the fourth century. Mithraea have been discovered throughout Great Britain, including in London near St. Paul's Cathedral, in Segontium in Wales, and along Hadrian's Wall in Northern England. Mithraism was also introduced into Northern Africa by Roman military recruits from abroad. At the height of its popularity, Mithraic temples could be found from one end of the empire to another, "from the banks of the Black Sea to the mountains of Scotland and to the borders of the great Sahara Desert." (Cumont 1956: 43, quoted in Ulansey 1989: 4; see also Gnoli 1987: 580-581).

Mithraic sites were very unevenly distributed, however. The greatest number of Mithraea have been discovered in Germany, due in large part to Rome's heavy military occupation of the region.15 Numerous Mithraic sites have also been found in Italy, especially in Ostia16 and in Rome where major mithraea have been discovered beneath the Baths of Caracalla, Circus Maximus, the Barbarini, Santa Prisca (Martin 1989:2) and most recently in the castra Peregrinorum, Roman barracks discovered during the renovations of S. Stefano Rotondo.17 One of the best preserved of all mithraea lies under the ancient church of San Clemente in Rome. However, while a considerable number of Mithraic temples have been found in Rome, Ostia, Numidia, Dalmatia, Britain and along the Rhine/Danube frontier, far less have been discovered in Greece, Egypt, and Syria. In other words, the cult was much more heavily concentrated in the western portions of the empire, the very territory later to be dominated by Roman Christianity.

Mithraeum at Hadrian's Wall

Mithraeum near Saarbrucken, Germany

Mithraeum Beneath Circus Maximus

(Rome)

.jpg)

Caeseria Mithraeum

(Palestine)

Dura-Europos Mithraeum

(Eastern Syria)

Mithraeum at Ostia Antica

Mithraism's greater concentration in Germany and Italy is further indicated by the distribution of votive offerings.18 According to Gordon (1972: 103), 49% of all such offerings have been found in the Rhine-Danube frontier provinces in Germany, and 31% in Italy [18% in Rome itself]. The sizeable number of Mithraic artifacts in Rome led Martin (1989: 2) to observe,

The flood of new Mithraic discoveries in the capital of the Roman world allowed Cumont to conclude by 1945 that Rome was the capital of Mithraism, and almost the seat of its papacy.19

Votive Offerings to Mithras

|

|

|

.%20Second%20century%20ceed.png)

Mithraic membership was limited to men. As Brandon (1954: 113) noted,

Mithraism appealed primarily to those sections of society in which the qualities of discipline, loyalty, austerity and comradeship were most natural and necessary. . . . it was essentially a masculine faith, and, except for one doubtful instance, there is no evidence that women could share in its fellowship or participate in its rites.20

Mithraists were primarily soldiers, merchants and imperial officials. Mithraism was a hierarchical religion, consisting of seven grades through which individuals would pass following the performance of a ritual that initiated them into the next higher grade.21 According to Gnoli (1987: 581), each grade was protected by a specific celestial body: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, the moon, the sun and Saturn. Such a hierarchical cult would have been highly compatible with those who were committed to military service, from which the cult drew most of its members, as well as with others aspiring to wealth, power and social status. Mithraism was clearly not a marginal religious sect appealing to social outsiders.

"The Mithraist of the sacred paintings is young, strong, unbearded, the image of social conformity, not of marginality. He accepted a slow, methodical, long-term commitment, for which the religious organization is designed to provide continuous support, so as to ensure his spiritual promotion. And promotion was achieved only by acceptance of and submission to authority." (Gordon 1972: 101).

Hierarchy was, thus, central to Mithraic cult organization. Those occupying the higher ritual levels in the cult organization would most probably have been the same people who occupied superior positions outside the cult organization. As Gordon (1972: 109) points out,

A good deal of nonsense has been talked about the egalitarian functions of the cult, as though the status differences of the outside world were simply forgotten in the religious context. That is surely no more true of Mithraism than of early Christianity.

The idea of an ordinary private soldier lording it over his, or any centurion, is absurd: it would have meant an enduring reversal of proper social relations impossible not only (but particularly) in the army but in the society of the Empire more generally.

Mithraic membership provided individuals with connections in widespread socioeconomic and political networks that would facilitate their social advancement, including potentially to the highest corridors of wealth and power, since even senators from prominent families were among its adherents. From the perspective of Roman political elites, Mithraism promoted discipline and loyalty as sacred virtues and a sense of brotherhood that would not only provide them with loyal followers and subjects, but that would also sanctify their rule. For this reason, Mithraism increasingly benefited from imperial patronage, and Mithras became progressively linked to, and eventually identified as, the Roman Sun God, the supreme god in the Roman pantheon. The ultimate conquest by Mithras was achieved when the Emperor Aurelian established Mithras as the Roman High God (Sol Invictus) in 274 CE,22 followed, according to Brandon (1954: 111) in 307 CE by the tetrarchs Diocletian, Galerius and Licinius dedicating an alter to Mithras at Carnuntum (one of the oldest centers of Mithraic worship in the Empire), proclaiming him fautori imperii sui ["the promoter of their empire"].23 Mithras, thus, became the special protector of both the emperors and the empire.24

Mithra's ascendancy in the Roman pantheon occurred rather quickly. Considerable Mithraic art depicts Mithras and Helios25 as equals, including scenes in which Mithras and Helios are pictured banqueting or riding a chariot together. One inscription that appeared frequently on votive offerings, was DSIOM, an abbreviation standing for deo invicto mithrae et soli socio, which translated means "to the Invincible God Mithras and the Sun his Ally" (Kaminski 2008: 8, following Shandruk 2004). Eventually, however, the title of Sol Invictus was transferred to Mithras, as Mithras supplanted/became Sol Invictus, Numerous inscriptions also exist, some dating as early as the third century CE, in which Mithras is himself referred to as Mithras Sol Invictus ["Mithras the unconquered sun"] (Roselaar 2014: 203).

.jpg)

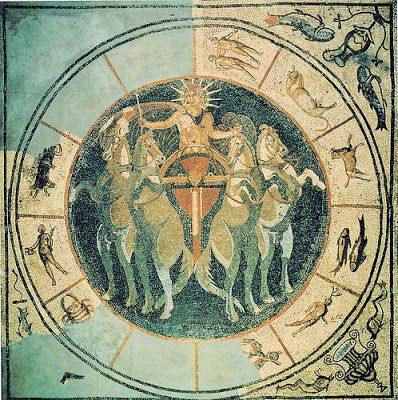

Mithras with Sol Invictus

(Invincible Sun God)

In one inscription discovered in Rome, dedicated to "One Zeus, Sarapis, Helios, maker of the universe, invincible", the name Sarapis26 was replaced with Mithras, suggesting that both gods were interchangeable, and that both were to be equated with Zeus and Helios.

Sol/Mithras Riding a Chariot Pulled by four Horses

In addition, through the portrayal of Mithras as the kosmokrator ("ruler of the cosmos"; cf. Ulansey 1989: 97, Figure 7.1) in artistic representations that mirror those of Apollo at Pompeii (ibid: 96, Figure 7.2), Mithras assumed the role and iconographic representation formerly attributed to Apollo.27

|

Apollo-Helios with Sphere

|

Mithras Holding the Celestial Globe

|

Mithras' association with the sun became especially important during the reign of the Emperor Julian ("Julian the Apostate") (361-363) who chose Mithras/the Sun as the focus of his efforts to restore paganism throughout the empire. By the fifth century, according to Roselaar (2014: 204), only six references to Mithras exist, most of which referenced his identification with the Sun. Mithras' identification with the sun was, in fact, the only element of Mithraism still discussed by Christian authors after c. 400 CE (ibid.). Indeed, according to Roselaar (ibid.) some Christian authors knew little about Mithras other than that he was associated with the sun.28

Apollo is to be regarded as the Sun in his course, the offspring of Zeus, named also Mithra, as he completes the cycle of the year" (Clement,

Homily 6.10, Appendix 14).

Ultimately, according to Ulansey (1989: 95-103; 1994: 107), by controlling the structure of the cosmos and the movement of all objects within it, Mithras became superior to all other celestial objects, including the sun. Thus, several Investiture scenes show the sun (Helios) kneeling before Mithras.

When Mithras is referred to as the unconquered sun, one naturally becomes curious whether or not there is a conquered sun. Mithraic iconography gives us the answer. All of those scenes depicting the sun god kneeling before Mithras or otherwise submitting to him make it abundantly clear that it is the sun itself who is actually the conquered sun. Mithras, therefore, becomes the unconquered sun by conquering the sun. He accomplishes this deed by means of the power represented by the symbol of the celestial pole which consists in his ability to shift the position of the celestial pole by moving the cosmic structure, which makes him more powerful than the sun. Mithras has become entitled to be called sun insofar as he has taken over the role of the kosmokrator formerly exercised by the sun itself. (Ulansey 1989: 110)

Investiture Scenes Showing Helios kneeling Before Mithras

|

|

|

(Ulansey 1989: 104, Figs. 7.9 & 7.10)

The Mithraeum

The Mithraeum was the principal place of worship for members of the Mithraic cult. Just as Christian churches have standard designs that reflect Christian myths, which can be observed with only minor variations in churches throughout the world, so also were the various Mithraea constructed using common design features that reflected Mithraic beliefs.29

Based on a belief in Mithra's birth in a grotto ("Born of the Rock"), most Mithraea were located either in caves, in subterranean cave-like structures or, if such locations were not available, in surface structures constructed to simulate caves.

Birth of Mithras

("Born of the Rock")

(Capitoline Museum, Rome)

The ceiling of a mithraeum contained a firmament filled with stars and reproductions of the planets and the various signs of the zodiac (Gnoli 1987: 581). As Kaminski (2008: 14-15) notes regarding the Mithraeum at Dura-Europos (170 CE),

"the floor plan of the Mithraeum is typical of most other Mithraeums that were part of the Roman Empire . . . . The vaulted ceiling was painted to look like the sky, blue with stars that were still painted white.

Dura-Europos Mithraeum

(showing ceiling)

Water played a purificatory role in Mithraism, as it does in Christianity. Consequently, Mithraea were also commonly located near springs, streams or other water sources (Gnoli 1987: 581), and a basin was often incorporated into the temple's structure (Pearse n.d.). Several of the Mithraea discovered at Ostia contained sunken basins in the floors, which, referencing the writings of Porphyry, Kaminski (2008: 17-18) suggests were used for ritual baptism (see also Lease 1980: 1312).

. . . the importance of water for all manner of ritual purposes is revealed by the water-basins and cisterns, by the representations of Oceanus, and also by the evident desire to locate temples in the vicinity of a river or a spring. Water-basins were clearly part of the basic equipment of all mithraea. (Clauss 2001: 73),

A 4th century Mithraeum has been discovered at the Roman port of Caesarea, the provincial capital of Palestine. Significantly, this temple was built in a large public building at the water's edge. Hopfe and Lease (1975: 10) note,

"it comes as no surprise that a Mithraic community would choose such a setting; in remembrance of Mithra's birth in a grotto, most Mithraea were located in cave-like structures. and a vaulted ceiling was highly favored."

The centerpiece of every Mithraeum, however, was the Tauroctony, a representation of Mithras, wearing a tunic, cloak and distinctive Phrygian cap, killing a bull by stabbing it in the neck.

Although the iconography of the cult varied a great deal from temple to temple, there is one element of the cult's iconography which was present in essentially the same form in every mithraeum and which, moreover, was clearly of the utmost importance to the cult's ideology; namely the so-called tauroctony, or bull-slaying scene, in which the god Mithras, accompanied by a series of other figures, is depicted in the act of killing the bull. (Ulansey 1989: 6)

An inscription in the Mithraeum under the Church of Santa Prisca in Rome referred to Mithras saving men by shedding the eternal blood of the bull.30 Thus, a depiction of Mithras' redemptive act, the slaying of the bull, occupied a central place in every mithraeum for the same reason that a representation of Jesus' redemptive act --his crucifixion-- occupied a central place in later Christian churches. As Sauer (2003: 136) points out, both soteriological acts were achieved through the spilling of blood.

Tauroctony

(Pio Clementino - Vatican Museums)

Tauroctony & Tauroctony Relief

(Capitoline Museum - Rome)

.jpg)

Tauroctony

(Circus Maximus Mithraeum - Rome)

Tauroctony Scene

(Dura-Europos Mithraeum - Eastern Syria)

Descriptions of the tauroctony discovered in different mithraea throughout the Roman Empire demonstrate that it followed a standard form, based on an established mythology.

Central to each mithraeum there was the tauroctony, the image of the bull slaying which was shown at the main altar. In the tauroctony Mithras is clad in a tunic, trousers, cloak, and a pointed cap usually called a Phrygian cap. He looks away from the bull while half-straddling its back, and pulling the bull's head back by its nostrils with his left hand. Mithras is plunging a dagger into the bull's shoulder with his right hand. Various figures surround this dramatic event. Under the bull a dog laps at the blood dripping from the wound and a scorpion attacks the bull's testicles. Often the bull's tail ends in wheat ears and a raven is perched on the bull's back. The scene is bracketed at the sides by the two smaller figures of Cautes and Cautopates,31 both of whom wear costume similar to that of Mithras. Cautes is to the right, holding an upraised and burning torch. Above him, in the upper left corner, is the sun god, Sol, in his chariot. On the viewer's left there is Cautopates, who holds a torch that points downards and is sometimes, but not always, burning. Above Cautopates in the upper right corner is the moon, Luna. This group of figures is almost always present, but there are variations, of which the most common is an added line of the signs of the zodiac over the top of the bull-sacrificing scene.

(http://www.mithraeum.info/history.htm)

At the rear of the mithraeum was always found a representation (generally a carved relief, but sometimes a painting or statue) of the principal icon of Mithraism: the tauroctony (bull-slaying scene). In this scene, which takes place within a grotto, Mithras is accompanied by a dog, snake, raven and scorpion. He is depicted in the act of killing a bull. Mithras is clad in a tunic, trousers, cape, and a pointed cap (known as a Phrygian cap). He is seen half-straddling the back of a bull with his right knee astride the bull's back. The bull had been forced to its knees. With his left hand, Mithras grabs the bull by its nostrils and pulls its head back. With his right hand, Mithras plunges a short dagger into the bull's throat. Three shoots of wheat spring from the wound. Various animals and human-like figures surround Mithras and the bull. A dog laps the blood flowing from the wound. A snake lies in the fore ground by the bull's right knee. A scorpion attacks the bull's genitals. A raven is perched on the bull's back. It appears to be bringing a message to Mithras. On the observer's left, a small, male figure is seen. He is known as Cautopates and is clad in the same fashion as Mithras. Cautes is holding an upraised, burning torch. On the observer's right is another small, male figure. He is known as Cautopates and is also clad in the same style as Mithras. Cautopates is also holding a burning torch, but this one is held downwards. Above the grotto and Cautes is the sun god, Sol, who is sitting in a chariot with the horses heading skyward. In front of Sol, is a small, child-appearing male figure. Above the grotto and Cautopates is another male figure in a chariot with the horses moving downward. In front of him is also seen a small, child-appearing male figure, Above him is the moon, Luna (Morse 1999: 34-35)

Though the sculpting is coarse, the figures of the tauroctony are easily identifiable. Mithra wears the familiar Phrygian cap, cape, and short skirt. He sits astride the sacrificial bull with a dagger in his right hand poised above the neck of the bull. He is looking upward over his right shoulder. On either side of him stand his companions. the torchbearers Cautes on the right with his torch lifted and Cautopates on the left with his torch pointed down. Beneath the bull one can barely see the figure of the serpent, but his head is clearly visible reaching up toward the wound Mithra has inflicted with his sword. From between the legs of Cautes, the dog who usually appears in the scenes leaps toward the right shoulder of the bull. Though they are not clear in this medallion. there may be representations of the sun and the moon Mithra. The lower third of the medallion is divided into three panels. Although these are not clearly identifiable in the medallion, other tauroctones indicate that these may be three scenes from the life of Mithra. In the left panel, there is a scene in which one figure is being crowned by another. In the central panel is a scene in which two figures appear to be eating a meal together. In the right panel there is a scene with two figures behind an animal, perhaps in a chariot drawn by the animal.

[Hopfe and Lease's (1975: 6-7) description of the tauroctony in the Caesarea Mithraeum in Palestine]

Another unique feature of the Mithraeum is the

Mithraic Kronos,32 the naked lion-headed figure frequently found in Mithraic temples. He is entwined by a serpent, with the snake's head often resting on the lion's head. The lion's mouth is often open. He is also usually represented having four wings, two keys (sometimes a single key) and a scepter in his hand (Pearse n.d.). This mythological representation is entirely restricted to Mithraic art.

Mithraic Kronos of Florence

The Mithraeum served as a meeting place for followers of the religion. The worship service, which culminated in a "common banquet," usually consisted of a few dozen people (Gnoli 1987: 581).

The second most important scene after the tauroctony in Mithraic art is the so-called banquet scene. The two scenes are sometimes sculpted on the opposite sides of the same relief. The banquet scene features Mithras and the Sun god banqueting on the hide of the slaughtered bull. (Pearse n.d.

)

The importance of the banquet in both mythology and ritual is demonstrated by its presence in Mithraic art.

In addition to this central scene . . . [the tauroctony] . . . there can be numerous smaller scenes which seem to represent episodes from Mithras' life. The most common scenes show Mithras being born from a rock, Mithras dragging the bull to a cave, plants springing from the blood and semen of the sacrificed bull, Mithras and the sun god, Sol, banqueting on the flesh of the bull while sitting on its skin, Sol investing Mithras with the power of the sun, and Mithras and Sol shaking hands over a burning altar, among others.

(http://www.mithraeum.info/history.htm)|

|

|

Mithraic Banquet / Eucharist

In imitation of

The Sacred Banquet following Mithras' Killing of the Bull

Mithraism and Christianity

Numerous beliefs became associated with Mithras that were typical of Hellenistic mystery religions and that eventually became incorporated into Christian belief. Morse (1999) lists 23 similarities between Mithraism and Christianity, including:33

1. Mithras was a god incarnated into human form;

2. Mithras was born on December 25th (Sol Invictus' birth date);

3. Mithras was born through a miraculous virgin birth witnessed by shepherds (Murdoch et.al. (n.d.);34

4. Mithras was born in a cave;35

5. Mithras was viewed as a Savior God who redeemed believers through his death and resurrection (see also Brandon 1954: 109-110; 1957: 125-126); Gordon 1972; Lease 1980: 1319);

6. Mithras was known as the "light of the world";

7. Mithras was believed to have performed miracles;

8. Mithraism preached a dualistic doctrine of good and evil and of heaven and earth;36

9. Mithras was a chaste god who remained celibate throughout his earthly life;

10. Baptisms were performed as a ritual of initiation into the Mithraic cult;37

11. Mithraic initiations were celebrated with a Eucharistic meal (see Sauer 2003: 35 (image 18), 136-137, (image 64);

12. Mithras was worshipped on Sunday (the day of the Sun God), the same day of the week eventually chosen for the worship of Jesus.

Lease (1980: 1329, note 173) adds that Christians borrowed artistic models and motifs from Mithraism, including depictions of Moses striking the rock for water during the Israelite Exodus from Egypt, Elijah's flight to heaven in a fiery chariot and Sampson's killing of a lion, many versions of which are remarkably similar to the portrayal of Mithras killing the bull in the tauroctony.

Sampson Fighting a Lion

(c. 1270)

Sampson Fighting a Lion

Lease (ibid.) describes yet another example of early Christian art that betrays a Mithraic influence.

An interesting example of such an apparent borrowing can also be found in the Coptic Museum, Cairo, exhibit 7118: a 6th century niche removed from the Coptic monastery of Apa Apollo, at Bawit in Upper Egypt, shows Jesus seated on his throne, which is in turn placed on a fiery chariot. A face on his right side, enclosed in a circle, is light and bright; while a face depicted on his left side is dark. This is clearly reminiscent of Mithraic representations: the central divine figure represents the bright sun of midday, while the smaller figures to the side show early day, or morning, and late day, or evening; just as Mithra represents the sun at its full power, and Cautes and Cautophates represent the rising and falling of that sun with their upturned and downturned torches.

Perhaps, most compelling, is the representation of Christ as Orpheus in which Jesus "uncannily resembles Mithra with his Phrygian cap." (ibid.)38

Christ as Orpheus

(Roman Catacombs)

Lease (1980: 1329, note 173) notes, however, that as Saxl (1931) long ago pointed out, many of the artistic similarities shared by Mithraism and Christianity consisted of elements belonging to the general world of Greco-Roman art during the imperial period. At the same time, Lease notes that, while Mithraism and Christianity shared many similarities in common, both had separate traditions from which they would likely have independently borrowed some of their shared beliefs and practices. Two examples:

Cave birth: . . . as early as the letter of Barnabas at the beginning of the second century, Christianity has a clear tradition that Jesus was born in a cave, though this is not mentioned in the canonical gospels. Some have felt that this belief is one of the clearest candidates available for a direct influence between Mithraism and Christianity. Benz, however, has shown conclusively that this Christian tradition does not come from a dependency on Mithraism, but rather from an ages old tradition in Palestine itself of holy shrines in caves. Indeed, at the end of the fourth century, Jerome writes that the cave is still visible in Bethlehem where Jesus was born, and over 100 years earlier Origen makes the same claim. (Lease 1980: 1321-1322; see also Abruzzi, The Birth of Jesus)

Baptism: Tertullian refers to an ablution of water in Mithraic rites. However, he does not speak specifically of baptism in anything approaching the Christian meaning of that word, and indeed both the origin and the context of such ritual washings are quite different for each religion. It is known that Zarathustra prescribed a purificatory washing as part of his religious reform of Persian ritual. . . . The sources for the Christian practice of baptism are so firmly anchored in the Jewish traditions of Palestine that there is scarcely a need to go outside of that context. Finally, little claim is raised that the widely spread practice of a purificatory washing before a ritual act, or as part of an initiation, throughout the Mediterranean Basin area was either unique only to Mithraism and Christianity or was derived from one common source. The central place of baptism in Christianity and the ideological content granted that act make it much different from anything described for the Mithraic community and it is difficult to posit any causal connection between the two religions' practice in this regard (Lease 1980: 1323-1324).

Over time, Mithraism and Christianity became increasingly competing sects. The expression of that competition evolved over time, reflecting both the intensity of the competition and the relative position of the two sects in relation to imperial power. Examining some three dozen passages written by Christian authors about Mithraism between the 2nd and 5th centuries, Roselaar (2014) argues that both the number and the tone of Christian comments changed over time.

Because so many similarities existed between Mithraic and Christian beliefs and rituals, several early Christian writers, including Justin (2nd century), Tertullian and Origen (3rd century) and Firmicus Maternus (4th century), accused Mithraists of copying Christian beliefs (Lease 1980: 1316). The earliest references explained that similarity as the result of Mithraic imitation of prior Christian beliefs and practices. Of the 9 passages identified by Roselaar that specifically accuse Mithraism of imitating Christian practice, 7 can be dated to the 2nd and early 3rd centuries, such as Justin Martyr's comment on the use of bread and water during Mithraic initiation ceremonies.

Which also the wicked demons have imitated in the mysteries of Mithras and handed down to be done; for that bread and a cup of water are placed with certain words said over them in the secret rites of initiation, you either know or can learn. (Justin Martyr, Apology 66.4; quoted in Roselaar 2014: 189)

However, while Justin

Martyr, writing in the 2nd century, proposed demons ("the imitation of the serpent of error") as the source of Mithraic copying of Christian practices, Tertullian, writing during the late 2nd and early 3rd centuries, saw more sinister forces at work. He attributed such copying to the direct work of the devil (see Roselaar 2014: 189-196; Gnoli 1987: 581-582), as can be seen in his comments on the Mithraists use of water in their purificatory rites.

In certain rites they are initiated by means of a bath so as to belong to Isis perhaps or Mithras. . . . Here too we observe the devil's zeal in hostility to the things of God, in that he also practises baptism among his own. (Tertullian, Baptism 5; quoted in Roselaar 2014: 191)

But does someone ask by whose ingenuity these things are explained so that they lead to heresy? By the Devil, whose work it is to twist the truth, who imitates the sacraments in his mysteries of divine idols. He even sprinkles some of his believers and faithful, and promises redemption of sin through the bath, and if I remember Mithras, he signs his soldiers on the forehead (or: ,by the water). He celebrates the sacrifice of the bread and shows an image of resurrection, and under the sword he denounces the crown. (Tertullian praescr. 40, 1-4; quoted in Roselaar 2014: 192)

The devil [is the inspirer of the heretics] whose work it is to pervert the truth, who with idolatrous mysteries endeavors to imitate the realities of the divine sacraments. Some he himself sprinkles as though in token of faith and loyalty; he promises forgiveness of sins through baptism; and if my memory does not fail me marks his own soldiers with the sign of Mithra on their foreheads, commemorates an offering of bread, introduces a mock resurrection, and with the sword opens the way to the crown (Tertullian, De paraescriptione haereticorum, 40:3-4).

In certain rites they are initiated by means of a bath, so as to belong to Isis perhaps or Mithras. [...] Here too we observe the devil's zeal in hostility to the things of God, in that he also practises baptism among his own. (Baptism 5, Appendix 5; quoted in Roselaar 2014: 191)

In a similar vein, Justin Martyr (100-165) accused Mithraists of teaching that Mithras was born in a cave in an explicit attempt to copy the Christian story of Jesus' birth in a cave. 39

By the second half of the third century, the number of Christians had already begun to rise significantly, a development that continued throughout the fourth century. Simutaneously, Christianity gained increasing political prominence, enhanced first by Constantine's conversion in 31340 and culminating in the Emperor Theodosius I declaring Christianity the official religion of the empire in 380. Mithraism, on the other hand, appears to have gradually declined in popularity during this same time period. It is at this time that all references to Mithraic imitation of Christianity disappear, and a new criticism arises: Christian authors begin accusing Mithraists of committing criminal behaviors, including incest and murder, during their ceremonial practices.41 They also accused Mithraism of being a foreign cult.

In the fourth century pagan cults gradually lost ground to Christianity. This resulted in a change in the way these cults were addressed by the Christians. Hardly any attention was given to the similarities between the cults which had been so important earlier. Instead many new themes were introduced, such as the accusation of crimes committed by Mithras and his followers, the foreign origin of the cult, the syncretistic nature of the Mithras cult, and his association with the Sun. Every opportunity was seized by the Christians to emphasize the supremacy felt by Christianity, and the defeat of the pagan gods, which they presented as inevitable. In the fifth century references to the Mithras cult almost disappeared, with the exception of the continuing attention given to Mithraic sun-worship. (Roselaar 2014: 208)

By the 5th century, when Christian power had been thoroughly established, all mention of Mithraism by Christian sources disappears (Roselaar 2014: 205-206). Once the Roman Church gained power,42 it eliminated all vestiges of competing pagan religions, including Mithraism its principal competitor. This was accomplished:

1. by destroying whatever literature these competing belief systems had produced;

2. by either acquiring the sacred buildings of competing religions, or by constructing its churches atop their ruins; and

3. by appropriating many of the beliefs and rituals associated with Mithraism and other pagan religions as its own.

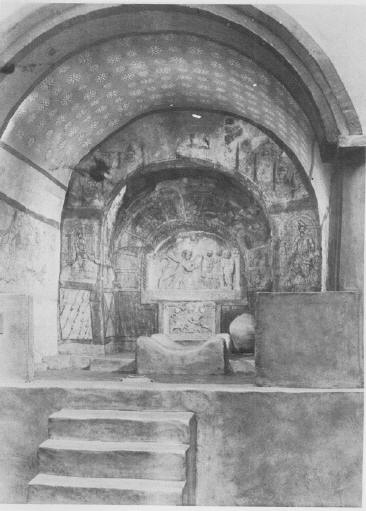

As indicated previously, many Mithraic temples, especially those in and around Rome, have been discovered buried under existing Christian churches.

On the very spot on which the last Taurobolium took place at the end of the fourth century, in the Phrygianum, today stands the Vatican's St. Peter's Basilica."

(Fingrut 1993; quoted in Tarkowski 1996:4)43

Mithraeum beneath Basilica di San Clemente

(Rome)

Mithraeum beneath Santa Prisca Church

(Rome)

As Christianity gained power and influence through rulers such as Constantine and Theodosius, it exhibited greater intolerance of pagan religions.44 Mithraists likely found themselves under increasing pressure to convert to Christianity if they wished to advance socially, or either maintain or elevate their positions in the imperial administration. Few Mithraic inscriptions are dated after 325, and most Mithraea seem to have been abandoned shortly thereafter. As has been the case for most indigenous belief systems, those pagan cults that did survive into the 5th century and beyond would have existed largely as remnant ritual communities scattered among rural populations far from the centers of power. However, as an organized belief system with a large network of adherents in both the military and the imperial administration heavily concentrated in Rome, Italy and Ostia, Mithraism would have represented a direct challenge to the emerging Christian Church. It, therefore, likely received greater direct hostility from the Church than did most other pagan belief systems.45

However, the continuing strength of Mithraic communities in and around Rome, particularly among the ruling elite (see Clauss 2001: 29-30), contributed to the intensity of their conflict with Christian authorities. The power of these communities is suggested by the brief reversal of Christian fortunes during the "Pagan Revival" under Emperor Julian (361-363). Julian was the nephew of Constantine and a Roman traditionalist who believed in the reestablishment of traditional Roman religions. His Tolerance Edict of 362 directly targeted the concentrated power of the Roman Church, which to this day refers to him as "Julian the Apostate." However, following this brief revival, Mithraism as an active cult vanished completely. The last inscription referring to Mithras dates from 391 (Roselaar 2014: 199), and the last known archaeological dating of a Mithraeum is 408 (Pearse n.d.).

A central question considered by Mithraic scholars concerns how directly the Church was responsible for the downfall of Mithraism. Sauer (1996) presents a detailed argument for the direct role Christian hostility played in the demise of Mithraism. In a subsequent book, Sauer (2003) provides substantial, detailed evidence to support his thesis of deliberate Christian destruction of pagan --in particular Mithraic-- temples and icons. According to Sauer (2003: 157),

There can be no doubt on the basis of written and archaeological evidence that the Christianization of the Roman Empire and early Medieval Europe involved the destruction of works of art on a scale never before seen in human history.

More precisely, he (ibid.: 152) adds,

While a small proportion of Mithraic temples on the Continent suffered willful destruction during the first two thirds of the fourth century, the vast majority of excavated temples, at least in those territories then still under Roman control, did not. . . . It was only between the AD 380s or 390s and the fifth century that catastrophe overtook Mithraism, and the artwork in the vast majority of devastated temples was smashed then. . . . It can hardly be coincidental that the archaeological evidence for destruction on a hitherto unparalleled scale coincides precisely with the period from the AD 380s onwards when written sources also attest that the destruction of pagan art was, with increasing frequency, tolerated and soon even sanctioned, encouraged and actively supported by the imperial government.

This was precisely the period when Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire and when the Roman Church consolidated its power within the empire.

The direct role of the Church in the demise of Mithraism has been a widely-accepted thesis among Mithraic scholars, as Gordon (1999: 683) notes in his largely critical review of Sauer's (1996) book.

In his main thesis, that in general worshippers continued to use mithraea up to the late 4th and even the first decade or two of the 5th c., and that their destruction was due to Christian hatred of a dangerous rival, Sauer is thus pushing at an open door.

Gordon, however, questions this thesis. He (ibid.: 684-686) proposes two distinct "theses" regarding the role Christians played in the demise of Mithraism. In his "strong thesis", Christians are viewed as having been actively involved in Mithraism's decline, intentionally destroying mithraea as part of their open hostility to the religion, as argued by Sauer and others (cf. Nicholson 1996). Gordon (ibid.: 682-683) lists several documented incidents in which Christians did, in fact, attack and destroy specific mithraea. However, he objects to the degree to which the strong thesis has uncritically dominated scholarly explanations for the demise of Mithraism and offers the "weak thesis" as an alternative explanation. In the weak thesis, the decline of Mithraism is the result of an organic process in which the success of Christianity indirectly caused the decline of Mithraism; as Christianity gained more adherents and became more dominant institutionally, the attraction of belonging to Mithraic ritual communities would have declined. Over time, Christian congregations had either occupied abandoned mithraea or purchased those experiencing a decline in membership (see also Martin 1989). The increasing Christianization of the army would also have contributed to the demise of Mithraism, as the military had been a leading stronghold of Mithraic recruitment, organization and power (Martin 1989: 12). Gordon (1999: 685, 687-688) offers various evidence that he believes validate his weak thesis and argues for the primacy of this thesis.

The end of Mithraism may be ascribed to the hostility of Christians in a weak or a strong sense. The weak sense would imply the gradual abandonment of worship as the Christianization of the State and of public life took ever more interventionist form, particularly in small cities and towns where individuals could scarcely escape notice. On that scenario, Mithraism would have ceased mainly as a result of indirect pressures, which caused its adherents to feel that the benefits of practising their beliefs had come to be outweighed by the costs. (Gordon 1999: 684-685)

As a further critique of the strong thesis, Gordon adds that in many cases it is simply not possible to determine conclusively whether the violent destruction of a particular mithraeum occurred years, or even centuries, later. It is perhaps most likely that both theses are correct. As Christianity gained prominence, it would have attracted more adherents than competing religions, inducing the member of competing cults to leave their ritual communities and join the increasingly prominent Christian ones. At the same time, ample evidence exists that clear hostility was directed towards Mithraism from the highest levels of the Christian hierarchy and that violent attacks were directed against local Mithraic congregations by neighboring Christian communities, at times instigated by members of the Church hierarchy. This dual level of violence by Christians against non-Christians, as well as among competing Christian sects, has a long and enduring history.

In the end, Mithraism was at a distinct disadvantage in competing with Christianity, due in large part due to two central features of the religion: Mithraism (1) allowed only male members, and (2) was an exclusive religious organization requiring initiates to undergo a series of increasingly difficult initiations in order to join the sect and rise within its ranks. Christianity, on the other hand, was an inclusive religion that was open to both males and females (indeed, many of its earliest adherents were female), and that required only a simple baptism to become a member. In addition, Mithraism largely functioned through local independent cult centers and lacked a central organization comparable to that of the Roman Church, which maintained hierarchically connected sees throughout the empire (in Rome, Carthage, Constantinople, Antioch and Alexandria), which better served Rome's imperial ambitions. Finally, Mithraism lacked a canon of sacred literature comparable to that of the Christian Church, which had produced extensive writings throughout the fist several centuries, culminating in a central canon in the fourth century.46 These three factors largely invalidate Ernest Renan's (1882: 579) statement that "if the growth of Christianity had been arrested by some mortal malady, the world would have been Mithraic." Quite the contrary, except for a brief resurgence during the Emperor Julian's "Pagan Revival", Mithraism declined steadily throughout the fourth and fifth centuries until it first survived only as a marginalized cult in isolated rural areas and then eventually ceased to exist at all as an organized religious community. It was completely replaced by Roman Christianity, which became the dominant religion throughout the empire during the fourth century and then the declared Imperial religion by the beginning of the fifth century, after which all other forms of religious expression were defined as heresy.

* * * * *

%20made%20of%20silver%20depicting%20Mithras,%20Saalburg%20Museum,%20Germany.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)