The Date of

Jesus' Birth

How

December 25th Became Jesus' Birthday

William S. Abruzzi

(2018)

.jpg)

Although December 25th

is the date on which most Christians celebrate Jesus' birth, no one

knows either the day or the year in which Jesus was born. The December 25th

date was established during the late 4th century, nearly 400 years

after Jesus died, and continues to be rejected by some 200-300 million Eastern

Orthodox Christians who celebrate the event on January 6th. Establishing the date of Jesus' birth was a work in progress for nearly four

centuries, during which various dates were proposed. It appears most likely that

the December 25th date resulted from the borrowing of a then-popular

pagan mid-winter celebration.

Early

Christians did not celebrate Jesus' birth. The

birth of Jesus did not acquire the same importance in early Christianity as did

Easter (Brown 1977: 28), which was celebrated shortly after Jesus' death.1 There

is no mention of its celebration in

Acts.

There is also no mention of

birth celebrations in the writings of early Christian writers such as Irenaeus

(c. 130-200) or Tertullian (c. 160-225).

Near the end

of the second century, Clement of Alexandria (150-215) (Stromata I,

21,145.5) ridiculed those who tried to establish the birth date of Jesus.

Indeed, birth celebrations were rejected as unchristian.

As late as the third century, Origen

of Alexandria (184-253) (Commentary on Matthew XIV,

6) objected to the

celebration of any birthday as being a pagan custom, pointing out that in the

Bible only the "heathen and the godless" (such as Pharaoh and Herod) celebrated

their birthdays.

Origen goes so far as to mock Roman

celebrations of birth anniversaries, a strong indication that Jesus' birth was

not marked with similar festivities at that time.

Jesus' birth also had no

theological significance. For Christians, it was Jesus' death and resurrection

that mattered, not his birth. Every Lord's Day

(later called Sunday) was celebrated as a "day of resurrection." From the very

beginning of Christianity the feast of Easter and the holy days associated with

it --which specifically celebrated Jesus' death and resurrection-- constituted

the foundation of Christian worship. Likewise, all festivals honoring his

apostles and later Christian martyrs were associated with their deaths, not their births. As Cullmann (1956: 21) notes,

Our Christmas festival of December

25th was unknown to the Christians of the first three centuries. Down to the

beginning of the fourth century this day, subsequently to become a central date

in the Christian Church, was allowed by the Christians to pass by unhonoured and

unsung, without any assembling together for worship, and without Christ's birth

being so much as mentioned.

And,

of course, there is no mention of snow or cold temperatures in either Matthew's

or Luke's infancy narrative, which effectively rules out a December birth.2 As

Jenkins (2011: 47) points out, "No sane Judean shepherd would have been out on

the hills watching his flocks in December." Having shepherds

"tending their flocks in the field"

in December (Luke 2: 8) demonstrates an ignorance of Palestinian climate and

sheepherding ecology in which animals are more likely to be corralled and

protected in the winter and pastured primarily during the warmer months when the

fields are covered with grass.

|

|

|

Bethlehem

(December 2015)

Jerusalem

(January 2013)

Christmas did not become a significant Christian holiday until the 4th

century CE. One indication of the late

date for the origin of Christmas is the fact that it recurs on a fixed calendar

date every year. This is a result of its being based on the later Roman

solar calendar rather than on the earlier Jewish

lunar

calendar, as is Easter, the celebration of which occurs on a different calendar date each

year. In addition, according to Kraabel (1982: 275), Jesus is not presented as

an infant in the earliest Christian art and literature, but rather is portrayed

sometimes as a youthful figure similar to Dionysius and Apollo, but more often

as an older, ageless figure. The earliest painting of the Virgin and Child, with

Balaam holding a scroll and pointing to a star (see Numbers 24: 17), is dated to

at least the third century and possibly later.

". . . a

star shall come forth out of Jacob, and a scepter shall rise out of Israel "

(Numbers 24: 17)

.jpg)

Virgin and Child

(Catacombs of St. Priscilla, Rome)

It

was only a matter of time, however, that Jesus' birth (Incarnation)

would take on soteriological importance.

Once faith in the

crucified and exalted Lord had been taken as the starting-point of theological

reflection on the question of Christ's person and work, his incarnation was

bound to become more and more central in devout speculation. (Cullmann

1956: 24)

Given

initial ecclesiastical indifference with respect to Jesus' birth date, numerous

proposed dates circulated during the earliest Christian centuries (see Cullmann

1942; Strittmatter 1956; Kraabel 1982). At the beginning of the third century,

Clement of Alexandria noted that Christian groups had

proposed several different days as the date of Jesus' birth. According to

Clement,

There are those who have determined not only the year of our Lord's birth, but

also the day; and they say that it took place in the 28th year of Augustus, and

in the 25th day of [the Egyptian month] Pachon

[May 20 in

our calendar]. . . . Further, others say that He was born on the 24th or 25th

of Pharmuthi [April 20 or 21]. (Clement, Stromateis 1.21.145;

quoted in McGowan 2012; see also Winter 1955:235)

Significantly, while

Clement discussed several proposed dates, he did not mention December 25th

as one of the dates claimed at the time. Clement himself

(Stromata 1:21) thought that Jesus was

born on November 18th and wrote,

From the birth of Christ,

therefore, to the death of Commodus are, in all, a hundred and ninety-four

years, one month, thirteen days.

[This calculates to be November 18th.]3

Several spring dates were proposed as the birth dates of Jesus, including April

2nd, April 19th, March 25th, March 28th and May 20th (see Cullmann 1956: 21-23;

Kraabel 1982: 274-275). The preference for a spring date was based on the belief

that the world was created in the spring. According to Genesis (1: 4-5),

it was on the first day of creation that

"God

separated the light from the darkness. God called the light Day, and the

darkness he called Night." The belief

was that on the first day of creation

light and darkness were divided into two equal parts. The first day of creation

must, therefore, have occurred on the

vernal equinox,

the date when night and day are of equal length. While the vernal equinox falls

on March 21st in our modern calendar, it occurred on March 25th in the Roman

calendar. Because Jesus represented the "new

creation," it was believed that his birth would have coincided with the date of

the original creation. This would have been consistent with the gospels claim

that Jesus was crucified in the spring. Since Jesus, as a perfect divine

being, would have lived complete (not partial) years, it follows that his

crucifixion would have occurred on March 25th.4

Based

on a slight modification of the above

argument, De Pascha Computus,

dated 243 CE (see Cullman 1956: 22; Talley 2000: 269), calculated that Jesus'

birth occurred on March 28th. Many early Christians associated Jesus with the

sun (see below), following Malachi's (4: 2) reference to the messiah as the

"sun of righteousness."

Genesis (1: 14-19) states that the sun was created on the fourth day of

creation. Following the belief that the first day of creation was March 25th,

the sun --and by extension Jesus' birth-- would have occurred on March 28th.

But for you who fear my

name the sun of righteousness shall rise, (Malachi 4:2)

A

similar theological arithmetic was used to

argue for

a December 25th birth date. During the third century, Julius Africanus claimed

that December 25th would have been Jesus' birth date, based on his belief that

Jesus would have been conceived

(the real beginning of his life) on March 25th and would have gestated a perfect

9 months in the womb. Africanus similarly assumed that Jesus

would have lived in perfect whole years and would, therefore, have been

crucified on March 25th. In

about 400 CE, Augustine of Hippo mentions a local dissident Christian group,

the Donatists,5

who kept Christmas festivals on December 25, but refused to celebrate the

Epiphany on January 6,

regarding it as an innovation (McGowan 2012).6

The use of the March 25th death date to justify the December 25th birth date clearly

illustrates the popularity of the former with regard to dating Jesus' birth.

Basing the latter date on the former date would have given it greater legitimacy

and, thus,

would have facilitated the Roman Church's attempt to establish the

orthodoxy of the December 25th date.

Egyptian Gnostic followers of Basilides in the 2nd century celebrated Jesus'

birthday on January 6th.

According to Ray (2000: 116-129), celebrations of the nativity in Palestine

initially took place in the middle of May. These celebrations were later moved

to January, and then finally to December during the 4th century. The Feast of the Nativity

continues to be celebrated on January 6th by the Armenian Orthodox

Church. A tradition is also found in Epiphanius (Panarion [c. 374-377] LI, MPG tome XLI, col. 928 ff.),

bishop of Salamis in Cyprus, according to which Jesus was born in the 42nd year of Augustus' reign (29 years

after the Jews had become subject to the Romans) on the 13th

Tebeth in Jewish,

the 11th Tybi in Egyptian, or the 8th

Audyneos in Syrian cylindrical

reckoning, which corresponds to the night linking the 5th and 6th of January in

the Julian calendar (743 years ab urbe condita)7

(Winter 1955:234).

According to Roll (2000: 274-275), the earliest "hard evidence" that December 25th

was celebrated as Jesus' birthday comes from the

Chronograph or almanac of

Furius Dionysius Philocalus (354 CE). This almanac contains three lists of

dates, which "taken together serve to indicate that by the year 336 the

nativity of Jesus stood at the start of the new year." (see also McGowan 2012).

However:

One list, the Fasti consulares,

a chronological listing of the consuls of Rome, includes the statement,

"Christ is born during the consulate of

C. Caesar Augustus and L. Aemilianus Paulus

on 25 December, a Friday, the 15th day of the new moon."

According to Roll

(2000: 275), this statement was awkwardly inserted into a secular list of Roman

consuls containing several factual errors, raising questions regarding its

authenticity.

A

second list, Depositio episcoporum, contains the names of Roman bishops who lived from 255 to

352 CE. The entries are arranged in order of their death dates

beginning on December 26. The first date

listed, December 25, is marked: natus Christus

in Betleem Judeae: "Christ was born in

Bethlehem of Judea" (McGowan 2012). However, the last two entries --Marcus, who died in

336 and Julius who died in 352-- are out of order, suggesting a later insertion

(Roll 2000: 275).

Since Sylvester, the most recent of the popes listed in correct order, died in December

335, Roll believes the source material can be reliably dated to the year 336. He

thus concludes, "the fact that it is arranged as if December 25 is the beginning

of the year . . . suggests that the nativity feast

had by then acquired its position as the start of the Christian year" (ibid.)

Significantly, a civil calendar included as part of the same Chronograph

notes December 25 as N(atalis) Invicti, a Roman civil holiday

honoring the birth of the invincible sun (ibid.),

with no mention of the nativity of Jesus (ibid.).

Equally problematic, according to Roll, is a

note contained in the third document Depositio martyrum, which begins:

"Christ is born on

the eighth of the calendar of January, in Bethlehem of Judea"

(ibid.).

The problem here is that the source in which this date is found is a list of

martyrs who died in Rome and who were buried in or near the city. The belief at

that time was that a Martyr's death date was their birthday into heaven, and that

this was the day that should be celebrated. However, Jesus' death date is not

indicated, making the inclusion of Jesus' birth date (as the day he was

physically born) among the list of birthdates (i.e., death dates) of martyrs

highly problematic. Roll (ibid.) suggests that Jesus' birth date may have

been a later insertion into this document.

It

was not until the late 4th century that December 25th

became established as the official date of the nativity in the West, and, even

then, had to be promoted among the general populace by offering a theological

justification. Gregory of Nazianzen

had preached sermons on the feasts of Christmas and the Epiphany in 379-380. In his sermon for the Epiphany, he

claimed to have been the exarchos

(originator) of the Christmas feast, not in 379,

but apparently shortly before (ibid.). John Chrysostom (

349-407),

Archbishop of Constantinople,

preached his sermon In diem natalem, on the date of the Nativity in 386, with the goal of justifying the introduction/imposition of this feast in the

Eastern Church less than ten years before (Roll 2000: 276). Chrysostom used

several arguments to support December 25th as Jesus' birth date.

Citing the words of Gamaliel:

"If it be of men, it will come to naught; but

if it be of God you cannot overthrow it, lest perhaps you be found even to fight

against God" (Acts V, 38-39).

Chrysostom argued that the validity of the December 25th date is confirmed by

its widespread acceptance by the Christian community within a comparatively

short period of time (Strittmatter

1942: 601-602). This

justification is both factually incorrect and illogical. It took over 300 years

for the majority of the Christian community to accept December 25th as the birth

date of Jesus. There was widespread resistance to this date, and it only

succeeded in becoming established as a result of its imposition by the Roman

Church. Also, a whole variety of false beliefs have been rather quickly

accepted by large numbers of people. Gamaliel's quote (assuming it is

authentic) could just as easily be used to validate the beliefs of other

religions, including Muslims, Hindus and Mormons.

In his sermon

In diem

natalem

of 386, Chrysostom supported this

position by appealing to the records of the census of Quirinius mentioned in

Lk 2:1-7

(Kraabel

1982: 278). He claimed that the December 25th feast originated at Rome, where the records of

the census of Quirinius were preserved, though those records were never

produced. Indeed, it is highly unlikely that they even existed or would in any way

have confirmed a December 25th date.

Chrysostom

further argued that, according to Luke (1: 8-13), Zechariah, the father of John

the Baptist, received the message of the archangel Gabriel six months before the

tidings were brought to Mary while performing his priestly rituals in the Holy

of Holies in the temple.

Now

while he was serving as priest before God when his division was on

duty, according to the custom of the priesthood, it fell to him by lot to enter

the temple of the Lord and burn incense. And the whole multitude of the people

were praying outside at the hour of incense. And there appeared to him an angel

of the Lord standing on the right side of the altar of incense. And Zechari′ah

was troubled when he saw him, and fear fell upon him. But the angel said to him,

"Do not be afraid, Zechari′ah, for your prayer is heard, and your wife Elizabeth

will bear you a son, and you shall call his name John."

(Luke 1:

8-13)

Only

on one day of the year, Chrysostom argued, was the high priest permitted to

enter the Holy of Holies; this was on the tenth day of the seventh month.

Calculating that Jesus' conception occurred 6 months later and that his birth

occurred 9 months after that, Chrysostom determined that Jesus was born in the

month of Appelaios (December in the Roman calendar).

There is, however,

no historical foundation for this; at no time was anyone named Zechariah ever a

High Priest, and the altar of incense was not located inside the Holy of Holies

(Winter 1955: 234). Furthermore, Luke's description of the birth of John is so

directly modeled on the birth of Samuel (1Samuel:1-2; see Freed 2001:87-89;

Abruzzi When Was Jesus Born?, note

35) that it cannot be considered an accurate historical account upon which to

determine the date of Jesus' birth.

Constantine and the Celebration of Christmas

Some

have associated the origin of the celebration of Christmas with the conversion

of Constantine to Christianity. Indeed, many have placed significant emphasis on

the personal role of Constantine and his program to recognize Christianity.

Other scholars, however, point to Constantine's decree in 321 limiting labor

on Sunday as evidence of his continuing devotion to

Sol Invictus, the

Roman Sun God, at least as much as to the day of the resurrection of Christ

(Talley 2000: 265).

Sol Invictus

While

Constantine was committed to making Constantinople the new Rome, several factors

contradict the argument that he introduced December 25th as the day

to celebrate Jesus' birth. One objection concerns the fact that no recognition

was given to Jesus' nativity on the day of the natalis invicti at

Constantinople throughout Constantine's lifetime (Talley 2000: 267). Indeed,

Roll (2000: 288) notes that, although Constantine resided in Constantinople from

324 until his death in 337 and deliberately had Constantinople

designed to include houses of Christian worship, the city did not mark the

Christmas feast until almost 380 CE (as represented in the sermons of Chrysostom

and Gregory Nazianzen), nearly half a century after Constantine's death. Talley

(2000: 271) emphasizes the same point.

Surely the majority of scholars

today understand the sermon of Gregory Nazianzen, preached at Constantinople on

the Feast of Lights (January 6) in 381, as indicating the introduction of the

December nativity festival at Constantinople by Gregory himself twelve days

earlier. In that sermon, Gregory refers to the celebration of the nativity on

the preceding December 25, describing himself as the exarchos of the feast, an

expression that most have understood to mean "institutor." Such an understanding

of the institution of Christmas at the eastern capital would be consistent with

Chrysostom's assertion in a Christmas sermon preached at Antioch in 386 that

this date for Christ's nativity had been known in the area for less than ten

years. If, with Cullmann and Auf der Maur and others who have urged a personal

role for Constantine, we accept December 380 as date of the introduction of

Christmas at Constantinople, and also suppose that the establishment of the

festival of Christ's nativity on the Dies natalis solis invicti at Rome was

under the influence of Constantine, how are we to account for the absence of

that festival at Constantinople during Constantine's lifetime? His limitation of

labor on Sunday seems to have continued in Constantinople, but neither there nor

elsewhere in the East do we encounter any attempt by Constantine to give

Christian expression to the Dies natalis Solis Invicti. This suggests that the

frequently asserted association of the two festivals was lost on Constantine.

As

already indicated, evidence exists that Christ's nativity was being

celebrated in North Africa prior to the accession of Constantine (Talley

2000: 265). Furthermore, Christmas was observed in Rome in 336, the year in which

Constantine celebrated his tricennalia

[30th anniversary]

at Constantinople, in contrast to his journey to Rome for the

vicennalia

ten years earlier (Talley 2000:270). As Talley (ibid.) notes,

If Constantine had any

interest in the coincidence of the nativity of Christ and the natales of Christ

and Sol Invictus at Rome, there is no sign that such an interest followed him to

Constantinople. The absence of a nativity festival on December 25 is

inexplicable at Constantinople, and even more so at Bethlehem, if Constantine

himself had any role in the establishment of such a festival at Rome.

(Talley 2000:270)

Constantine was not baptized a Christian until shortly before he died. He also

never renounced his devotion to the Sun. In 321 CE he designated Sunday, the

traditional Roman day dedicated to the sun, as the Christian "Lord's Day,"

making it an officially sanctioned Roman holy day and weekly day of rest. This

act of giving the Christian Sunday legal status would have been consistent with

his attempt to integrate traditional Roman sun worship into Christianity which,

because it was widely dispersed throughout the empire and organized into a

central hierarchical church organization, served his goal of uniting

the empire. As Cullmann (1956: 31) clearly notes,

Constantine was not so much a

Christian as a conscious syncretist: he strove after a synthesis of Christianity

and the valuable elements in paganism. Christianity was the religion he most

favored simply because its organization made it the best able to unite the

empire. . . . But Constantine may well have thought that the multifarious

religions of the empire could somehow be carried on within the single framework

of Christianity. We hear nothing of any deliberate attack on paganism cults. All

his life, however, he promoted the worship of the sun. He allowed himself to be

represented in two statues as the sun god with shining rays, and permitted the

following inscription to be placed on the pedestal: 'To Constantine, who brings

light like the sun'.

Several other sources indicate Constantine's continuing devotion to the

sun. One of these sources involves the coins minted during Constantine's reign

(see Alfoldi 1932; Bruun 1962; Schweich 1984; Kiernan 2001; Dunning 2003; Clark

2009; Constantine the Great Coins;

Christian Symbols on Roman Coins).

Images of Sol

Invictus and other

pagan symbols abound on Roman coins throughout Constantine's reign. By contrast,

"of the approximately 1,363 coins of Constantine . . . roughly one percent might

be classified as having Christian symbols" (Constantine

the Great Coins). The most common symbols that can be interpreted

as Christian include the chi-rho

and other variations on the cross. However, the use of these symbols pre-dates Christianity; consequently,

they cannot be assumed to be Christian symbols when they appear on Constantinian coins (see Bruun 1962; Dunning 2003). The chi-rho, for example,

appeared for the first time in the third century BCE on a Greek bronze coin

during Ptolemy's reign (ibid.; Dunning 2003: 7). Significantly,

the first overtly Christian legend on a Roman coin does not appear until 350 (Christian

Symbols on Roman Coins), a full 13 years after Constantine died.

The coin contains a small chi-rho held by

the emperor while he is being crowned by Victory. The accompanying legend

consists of the famous words reportedly said by God to Constantine in his vision

before his victory in the battle of Milvian Bridge:

HOC SIGNO VICTOR ERIS

("With the sign, you will be victorious"). The Christian interpretation of this

vision derives largely from Eusebius (260-339), the bishop of Caesarea and a

Christian polemicist who promoted Constantine as the first "Christian" emperor

in his History of the Church

and The Life of

Constantine. It is not clear whether Constantine

saw such a vision, or if he believed he had that the god in question was the Christian god (see Dunning 2003; Wallraff 2001).

|

Coin with Constantine and Sol

|

.jpg)

Commemorative coin with She-Wolf Nursing

Romulus and Remus, Mythical Founders of Rome

(330 CE) |

.png)

Medallion with Constantine wearing a Helmet

containing the Chi Rho symbol

(315 CE)

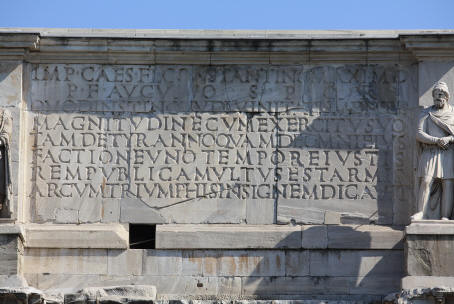

Also,

while several images of Sol appear on the Arch of Constantine, no images of

Jesus or any symbols that can be considered Christian appear anywhere on the

arch (see Wallraff 2001;

Marlowe 2006).

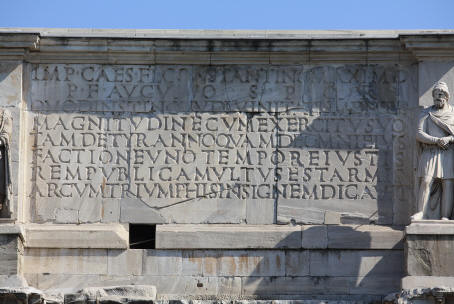

Sol on the east facade of Constantine's Arch

In

describing Constantine's Arch, Wallraff (2001: 256) states rather clearly,

Constantine won his victory over

Maxentius instinctu divinitatis, as the famous inscription on his triumphal arch

reads. It has been debated as to what deity this is referring; in any case there

is no iconographic evidence whatsoever to support a Christian interpretation. On

the other hand, the arch is full of solar symbols. There can be no doubt that at

this stage Sol invictus was at least as important to Constantine as Jesus

Christ.

It is likely, therefore, that the inscription instinctu divinitatis

("inspired by the divine")

displayed prominently on the arch refers to Sol rather than to Jesus.

Translation

To the Emperor Caesar Flavius Constantinus, the greatest, pious, and blessed

Augustus: because he,

inspired by the divine, and by the

greatness of his mind, has delivered the state from the tyrant and all of his

followers at the same time, with his army and just force of arms, the Senate and

People of Rome have dedicated this arch, decorated with triumphs.

Marlowe (2006) describes the size and placement of the giant colossus of Sol

(125 feet, if the rays extending from the crown are included) that stood

adjacent to the Constantine's Arch in the Roman Forum. She maintains that the

statue was framed by the arch and that it was situated in such a way as to

dominate the entire landscape of the Forum. Similarly, the

principal forum at Constantinople contained an imposing column some 115 feet

high upon which stood a statue of Constantine portrayed with the attributes of

Apollo, the Greek sun god. The emperor's devotion to the sun was, thus,

evidently alive and well, with no indication that he abandoned the sun god for

Jesus.

Constantine's Column Today

(Istanbul)

How and Why December 25th Became

Jesus' Birthday

Once

it is understood that December 25th was not the original day on which

Christians believed Jesus was born and that this specific date was not

established by the Roman Church until the late fourth century, the question becomes how and why

did December 25th become the official date for celebrating the nativity of Jesus

throughout Western (though not Eastern) Christianity.8 Two explanations have

dominated modern discussions of the issue: one liturgical,

the other historical.9

Thomas J. Talley, an American

Anglican liturgist and a proponent of the liturgical explanation [a.k.a., the

Calculation Hypothesis]

supports the explanation initially presented by Louis Duchesne (1843-1922) in

which

the nativity date

of December 25 was arrived at by computation from the date already established

for the passion in the West early in the third century, March 25. The primitive

pascha celebrated the entire mystery of Christ, including the incarnation, and

christological development early identified the point of incarnation as the

conception at the annunciation to Mary. This would put Christ's nativity nine

months after the March 25 date assigned to the passion and conception, on

December 25.

(Talley 2000: 266)

In other words, a March 25th

conception was followed by a perfect nine-month pregnancy, resulting in a December

25th birth date. The conception date would, thus, have been identical

to

Jesus' death date. Duchesne theorized that the December 25th date was

reached by taking the traditional date of Jesus' death, March 25, and concluding

that it was also the date of his conception, following the numerological belief

that Jesus would have lived an exact number of years. His birth would,

therefore, have occurred on December 25th, exactly nine months after his

conception. Talley (ibid.) supports this hypothesis by claiming that these

dates of conception and death were accepted by Augustine

10

in an early North

African tractate, and were contained in traditions referred to by both John

Chrysostom and Epiphanius.11

Duchesne's thesis is, of course, simply a rehash of the kind of arguments used by early

Christians to justify a whole variety of different birth dates; indeed, his

explanation is essentially a modern retelling of Julius Africanus' thesis in the

early third century (see above).

The

Catholic Encyclopedia,

however, notes that "there is no contemporary evidence for the celebration in

the fourth century of Christ's conception on 25 March,"12 rendering Duchesne's

theory moot.13

According to Cullmann (1956: 22), the

January 6th birth date for Jesus in the East was rationalized in a manner similar to that of December 25th in the

West. January 6th is 9 months after April 6th, which was regarded there as the

date of Jesus' conception and crucifixion. A liturgical explanation for this

date is, therefore, equally problematic.

Inasmuch as beliefs evolve over

time and change from place to place, it is necessary to examine the time and

place that the institutionalization of Jesus' birth date occurred in order to

understand both why a date was established at all, as well as why a specific

date was chosen. In addition, since various dates were proposed and accepted, it

is necessary to understand the process through which one date became canonical

and all others declared heretical. To achieve this goal, it is necessary to

focus on the political conflict that existed among competing Church factions and

the role that the institutionalization of one date to the exclusion of all

others played in the consolidation of the Roman Church's power and authority

over other churches. More

specifically, if we are to understand why Jesus' birth date became

celebrated on December 25th in the West, we

need to explain it systematically; i.e., we must consistently explain:

(1) why the celebration of

Jesus' birth emerged at all;

(2) why it was celebrated on

December 25th initially only in the west; and

(3) why it was originally

celebrated on January 6th in the east.

We also need to understand why these two dates

became significant theological issues in the ongoing conflict between eastern and

western Christianity. In order to achieve such an explanation, we need to

examine the context in which the celebration of Christmas emerged; it did not

occur in a vacuum. To this end, the

promotion and eventual supremacy of the December 25th date for Jesus' birth must be

understood as part of the ecclesiastical politics of the day.

. . . mainline or orthodox

(Nicene) Christians undertook to defend their beliefs against, on one hand

non-Christians of whatever belief system, and on the other hand fellow

Christians in various splinter groups who supported beliefs and practices

condemned by the mainline Church as "heresy." It was in this atmosphere of

polemics and fear for the unity of the Christian movement in the fourth century

that the new feast of Christmas came to be used as a means of promulgating

Nicene doctrine concerning the nature of the incarnation and the equality of the

Son with the Father, while castigating, explicitly or implicitly, both

non-Christian festivals and sun-worship practices, and the threat posed to the

Church from various Christian factions.

. . . by the fifth century

bishops were making use of the feast to counter non-mainline teachings, a

process strikingly visible in the ten consecutive Christmas sermons of Leo I.

(Roll

2000: 278-279)14

Numerous competing Christian sects existed

throughout the Roman Empire. Eventually, it was the church in Rome, with

imperial support, that came to dominate the faith and to define authoritative

Christian beliefs and practices. In the process of Christianity becoming the official religion of the Roman

Empire, and of the Roman church becoming the official Christian authority within

the empire, Western Christianity incorporated into its theology and structure several

beliefs, images and institutions that it borrowed from pagan Roman religious

practice.15 Included

among these were the

establishment of "holy places", a belief in saints (i.e., spirits of departed

individual who, because of their divine status, could assist those still

living), a college of religious officials, and the establishment of a

centrally-controlled calendar of holy days that organized

religious worship throughout the empire (see Helgeland 1980: 1292-1298;

Kraabel 1982: 276; Markus 1994).

Indeed, as

McGowan (2012) points out, "many early elements of Christian worship --including

eucharistic meals, meals honoring martyrs, and much early Christian funerary

art-- would have been quite comprehensible to pagan observers."

Kraabel (1982: 276) similarly comments on the ease

with which the beliefs and rituals associated with "holy places" and religious

worship directed by the imperial Roman calendar

passed "smoothly and

almost unnoticed into a new Roman religion"

(i.e. Christianity).

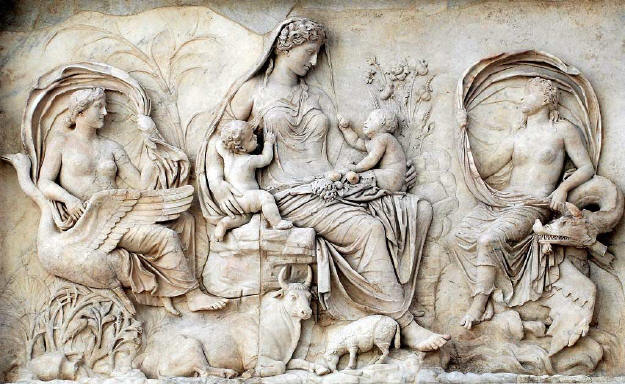

Indeed, the celebration of Christmas and

Easter, which together incorporate a belief in a virgin birth, the incarnate

union of a male god and a human female, and a divine salvic death and

resurrection, all have precedence in pagan beliefs and practices.16

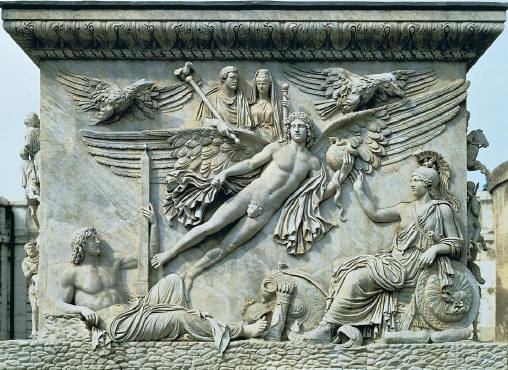

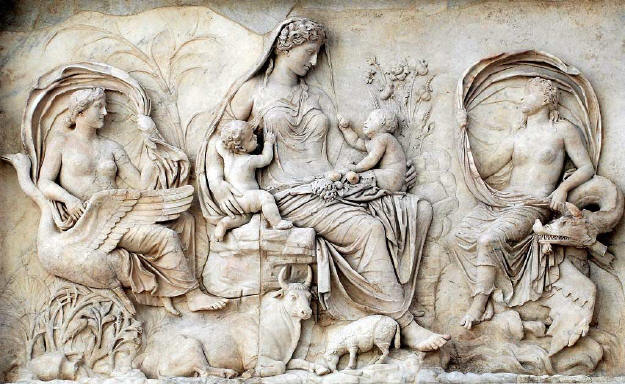

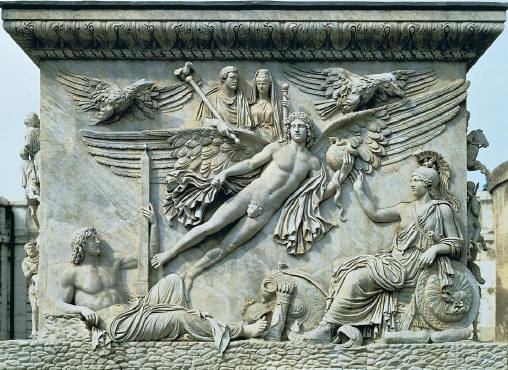

Roman belief in the deification of individuals is illustrated in

the base of a column currently located in

the Vatican courtyard, which presents the Apotheosis of Antoninus Pius and

Faustina. One of the iconographic features adopted by Christianity from

Greco-Roman paganism was the portrayal of winged divine beings.

Apotheosis of Antoninus Pius and Faustina

pedestal of the Column of Antoninus Pius

(c.

161 CE - Rome)

Iris the Heavenly Messenger

in Greek Mythology

|

Nike, the

Greek Goddess of Victory

(Ephesus)

|

.jpg)

Winged Victory of Samothrace

(190 BC) |

The Christian image of a winged

angel (below) follows very closely on that of Greek and Roman images of divine

beings.

%20on%20the%20Prince's%20Sarcophagus,%20discovered%20in%20Istanbul%20in%201930%20(4th%20c.)-copy..jpg)

Oldest Representation of a Winged Angel

Prince's Sarcophagus

(Istanbul,

4th century)

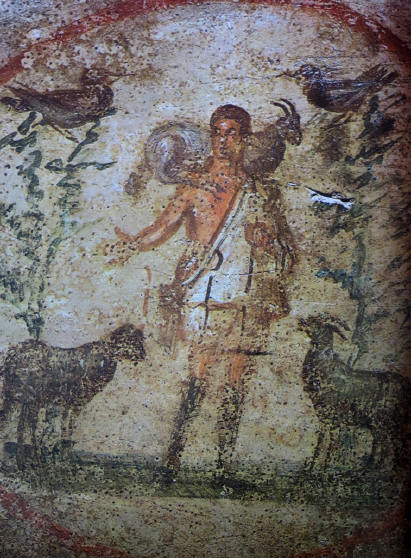

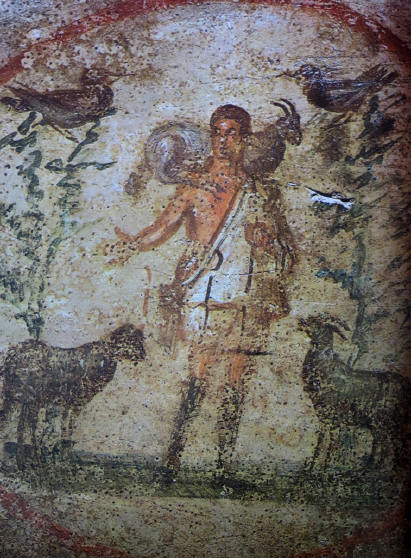

Images of Jesus as the

"Good Shepherd" also have precedence in earlier Greek and Roman portrayals.

Jesus as

Good Shepherd

(Catacombs

of Priscilla-Rome-3rd century)

Christ as Shepherd of Souls -allegory

originated in image of Moschophoros from

Greek art

The Good Shepherd

(Domitilla Catacombs - Rome)

|

,%20(Acropolis%20Museum,%20Athens),%20ca.%20470%20BC.jpg)

The Moschophoros

(Calf-bearer),

(ca. 470 BCE)

Acropolis Museum, Athens

|

Hermes crioforo

("ram-bearer")

|

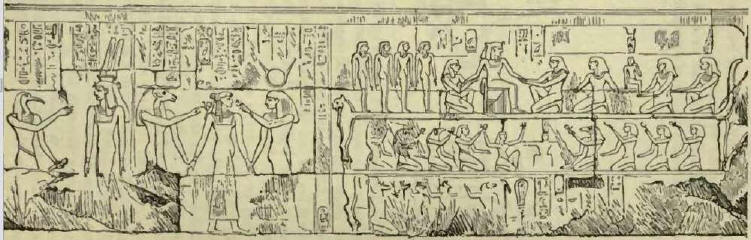

Similarly, a

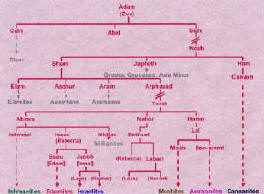

divine birth was attributed to many gods in the ancient world.

Scenes depicting

the divine birth of Amenhotep III

(c. 1390 - c. 1352 BCE)

Miraculous Birth of

the Buddha from the side of his mother

Conception of Alexander the Great 17

Birth of Romulus

and Remus through the God Mars

impregnating

the Vestal Virgin Rhea Silvia

18

The newly

instituted Christian calendar performed the same social and

political function

as the pagan Roman calendar it replaced: the promotion of imperial unity.

In pagan Rome, December

25th was an important annual festival celebrated in honor of the rising sun, the

supreme deity established by Aurelean and promoted by Constantine, who pursued a

deliberate policy of uniting the worship of the sun with the worship of Jesus.

To this end, the official establishment of Christmas on December 25th followed

logically from the previous imposition by the Roman Church (also under Constantine's

direction) of Sunday as both the "Lord's Day" and the day

for the celebration of Easter.19

The uniformity imposed

on the celebration of Easter went along with the uniformity imposed on the

celebration of "the most honorable day of the sun," which Constantine had set

aside four years earlier as the weekly day of rest (C. Just. III.12).

This also contributed towards unifying the empire --under a monotheistic

sun-religion. While the movement was in the direction of Christianity, the

formulation did not exclude the cult of Sol Invictus. . . . This process,

begun by Constantine, was continued and expanded by later emperors. In 386

explicitly religious reasons were given for reiterating Sunday as a day free of

all business (C. Theod. II.8.18). Finally in 425 the "Church Year" is legally in

place: each Sunday, plus Christmas, Epiphany, Easter and Pentecost are to be

solemn free from circus, theater and other spectacles (C. Theod. XV.15.5). Even

pagans in their "stupidity" and Jews in their "madness" must conform. . .

.

As the empire moved in a Christian direction, so also did the calendar,

including with Christmas.

(Kraabel 1982: 279)

In the newly

established Church

calendar, Christmas functioned originally as a counter to the

Natalis Solis

lnvicti. ("Birthday of the Unconquerable Sun'') on December 25,

which had been

inserted into the Roman calendar by the emperor Aurelean in 274 following his

defeat of Palmyra the previous year (Strittmatter 1942: 613). Under Aurelean, Sol Invictus

became the supreme deity in the Roman pantheon, and the traditional day of the

winter solstice, bruma (December 25), became the

Natalis Solis lnvicti,

the paramount feast in the calendar of the Empire (the

sun, "born" on that day, "grew" every day thereafter). At the same time,

Aurelean

dedicated a magnificent temple to the newly established supreme god in the

Campus Agrippae and formed a priestly college of senatorial rank (perhaps a

model for the College of Cardinals in the Roman Church) charged with

the responsibility of serving this new supreme deity (Strittmatter 1942: 613). Numerous Roman gods

had been associated with the sun at one time or another.

Macrobius (Saturnalia

1 17-23, c. 400) argued that Apollo, Bacchus, Mars, Mercury, Asclepius,

Hercules, Adonis, Osiris, Saturn and Jupiter had all at one time or another been identified with the

sun. However, under Aurelean, Sol Invictus became the supreme deity.

Ultimately,

the emperor Julian even wrote a lengthy

Hymn to King Helios

during his brief reign (361-363)

(Kraabel 1982; 278).

One by one, a whole series of divinities -Apollo,

whose numerous epithets are carefully reviewed; Liber or Bacchus, Mars,

Mercury, Aesculapius, Hercules, Adonis, Osiris, Saturn, Jupiter-are identified

as one deity, the Sun. It is not insignificant that the last Pagan emperor of

Rome should have left us an elaborate panegyric on this divinity, whose

spiritual offspring he believed himself to be.

(Strittmatter 1942: 613-614)

Worship of the

sun eventually passed to Mithras, the new

rising god who, while initially considered Sol Invictus' ally, eventually

replaced him as the paramount Roman solar deity. As

Christianity arose and competed with

Mithraism for both adherents and influence

during the third and fourth centuries (with Jesus serving as Rome's

most recent incarnation of sun worship),

Mithraism became a particular focus of Christian hostility.

Jesus and the Rising Sun

As Christianity spread from

its Palestinian homeland into the wider Roman Empire, it encountered numerous

other religions with which it had to compete and whose beliefs it would have had

to confront or accommodate, if it was to succeed.

First and foremost was the official religion

of the empire, which had shifted towards the primary worship of the Sun at the

head of a pantheon of gods, especially, as indicated above, after the emperor Aurelian (270-275

CE)

promoted Sol Invictus to the position of a monotheistic state god and

established December 25th as the day to celebrate Sol Invictus'

birth (McGowan 2012).

As the Christian Church

pursued religious leadership in the Empire, it would have been in the Church's

interest to make that transition as easy as possible in order to convert Roman

pagans. Linking Jesus' birth with that of the sun would have been central to

that process. Consequently, it would have been useful to link Jesus to the sun,

as was done for several previous Roman gods (see

Macrobius Saturnalia

1 17-23, op cit.).

Linking Christ with the Sun did, in fact, occur early in the development of Christian thought.

Constituting a form of

solar christology, Christ was

frequently

represented as the sun; indeed, among his titles was

Sol iustitiae, ["Sun of Justice"] (Roselaar (2014: 204).

By the middle of the

second century the term 'Sunday' replaced the former 'Lord's Day', indicating

that in Christian thought the resurrection of Christ had already become

associated with the symbolism of the sun.

Those who argue for the derivation of Christmas from Aurelian's solar festival

on the winter solstice regularly appeal to that image of Christ as Helios,

driving the chariot of the Sun across the heavens, as evidence for the

identification of the date of Christ's birth with that of the Sun.

(Talley 2000: 269)

|

_(1499-1500).jpg)

|

Sol Iustitiae

("Sun of Righteousness")

Albrecht Durer

1499/1500

National Gallery of Art

Washington, DC

|

Christian tradition eventually assigned the

birthdays of John the Baptist and Jesus to the summer and winter solstices

(June 24th and December 25th) respectively, having John born on the day from

which the sun

decreases and Jesus born on

the day from which it

increases (see Winter

1955:235, note 15). This association of John and Jesus with the changing

position of the sun continued the increasing theological linkage and

subordination of John to Jesus initiated in and elaborated through the four

canonical gospels (see Abruzzi,

The Birth of Jesus).

The Venerable Bede

(673-735) in his

De temporum ratione

(725), an influential medieval source for calculating Easter and other

significant dates in biblical history, more precisely defined Christian

beliefs regarding the births of Jesus and John by placing them within ancient

Roman calculations for the solstices and equinoxes. In Bede's reckoning, Jesus

was conceived and crucified on the 8th kalends of April [March 25], at

the

spring equinox. and born on the 8th kalends of January (December

25th) at the

winter solstice, while the Baptist was conceived at the

autumn

equinox on the 8th kalends of October [September 24] and born at the

summer solstice on the 8th kalends of July [June 24] (see Nothaft

2011: 507). Nothaft (ibid.) adds that other sources existed that also applied the symbolism of increasing and decreasing light associated with

the births of Jesus and John respectively. One source, claiming to have been

written by John Chrysostom himself, maintained that this symbolism was already

suggested in the Gospel of John (3:30) where John the Baptist, referring to

Jesus, is quoted as saying,

"He must increase; I must decrease."

According to Roll (2000: 289),

several early patristic writings contained references to Jesus as representing

the light or the "new sun".

The oldest extant

liturgical texts for Christmas are found in the Veronensis and include nine sets

of formularies which link the themes of light and the birth of Christ. The

opening prayer for Mass at midnight in the contemporary Roman Missal, based on

the Gelasian Sacramentary, echoes the theme of Christ as light, and implicitly

the "true sun" of the world.

(Roll 2000:

289)

As

mentioned previously, the author of

De Pascha

Computus

writing in 243, attempted to link

Christ's birth with that of the Sun. Ambrose (c. 339-397), bishop of Milan, described Christ as

"the true sun, who outshone the fallen gods of the old order" (McGowan 2012),

and in a Christmas sermon stated,

Well do Christian people call this holy day, on

which our Lord was born, the day of the new sun; and they assert it so

insistently that even Jews and pagans agree with them in using that name for it.

We are happy to accept and maintain this view, because with the dayspring of the

Saviour, not only is the salvation of mankind renewed, but also the splendour of

the sun. (quoted in Cullmann 1956: 36)

Pope Leo the Great (440-461) also employed

analogies of Jesus with light and with the sun in several of his Christmas

sermons, contrasting him to the "darkness" represented by one or another

non-Christian religions and heretical Christian sects (Roll 2000: 289).

Augustine

alluded to the pagan festival of December

25th in his summons to Christians not to worship the sun on this day, like the

pagans, but him who created the sun (Cullmann 1956: 31).

Similarly, in his Christmas

sermon in 386, John Chrysostom, archbishop of Constantinople, preached,

"Let us rejoice, therefore, and

exult, beloved. For if John in his mother's womb leaped at Mary's coming to

Elizabeth, much more ought we, who have seen not Mary, but our Saviour born this day to leap and exult, to marvel and stand amazed over the magnitude of God's

dispensation, which exceeds all thought. For consider how great a thing it would

be to behold the sun descended from heaven and running about the earth,

emitting hence its rays to all. But if in the case of a visible body of light

this occurrence would strike all beholders, reflect with me and consider what

it is to see the Sun of Righteousness sending forth His rays from our flesh and

illuminating our souls. (quoted in Strittmatter 1942: 600)

20

Talley (2000) points out

that even Constantine, who himself converted to Christianity and, in the process,

became instrumental in Christianity becoming the official religion of the

empire, made an explicit connection between Jesus and the sun.

That the emperor . . .

[Constantine] . . . intended the new capital to be a clearly Christian city did

not mean that he had renounced his devotion to the Sun. At Constantinople, the

principal forum was adorned with a porphyry column upon which stood a figure of

Constantine with the attributes of Apollo. The emperor's solar piety was

evidently alive and well, but did he there, as he is said to have done at Rome,

seek to associate the nativity of Jesus with that of Sol Invictus? . . . It

seems beyond dispute that in some sense or other Constantine associated Christ

with the Sun, as had many before him on the basis of Mal 4:2. Such

identification of Christ as "Sun of Righteousness" found iconographic expression

at Rome in a famous mosaic ceiling in the tomb of the Julii in the Vatican

necropolis

(Talley 2000:

268-269).21

J

esus

as Helios

(Tomb of

Julii, Vatican Necropolis)

22

Several

scholars have further argued that the adoption by the Christian Church of pagan

Roman religious practices and institutions, most importantly those associated

with the worship of the sun, was not coincidental. Several early Christian authorities

were well aware that they were adopting a traditional Roman midwinter

ceremony as Jesus' birthday and encouraged their congregations in this regard. As Cullmann (1956: 31) points out, the numerous statements made by early ecclesiastical authorities "show

that the fixing of the festival of Christ's birth on December 25th was not done

in ignorance of the pagan significance of the day."23 Indeed, in a

sermon attributed to Maximus of Turin (c. 465), the bishop called for the

explicit adoption by Christians of the Roman celebration of the birth of the

sun.

The common people do

well, indeed, to call this birthday of our Lord the 'new sun,' and make the

assertion with such emphasis that Jew and Gentile find themselves in agreement

in this terminology. Let us willingly make this custom our own, for with the

Saviour's rising not only the salvation of the human race, but also the radiance

of the sun itself is renewed. (quoted in

Strittmatter 1942: 616-617)

It was also not a

coincidence that Sunday, named for the sun and reserved in Roman religion for

the worship of the sun, was adopted by Roman Christianity as the day to worship

Jesus and to celebrate his resurrection. Jesus replaced all previous Roman solar

deities as the personification of the sun and the one god integral to the

emergence of the Christian calendar, which completely replaced the previously

dominant Imperial calendar.

The Sun God was then

the official supreme deity of the empire taken over by Constantine. The

Christmas festival was inaugurated with the ''triumph of Christianity," to

supplant this cult of the sun with another. From the Christian side, this

process was aided by prior developments in christology including the application

of the term ''Sun of Righteousness" (Mal. 4:2) to Christ. The earliest instance

is apparently in chap. XI of_ the Protreptikos of Clement of Alexandria, who

died ca. 215. It occurs in a passage from de Pascha Computus (AD 243) quoted at

the beginning of this essay. It is then frequently in Origen and later writers.

When these texts are put together with others which use sol or helios of Christ

without direct reference to the Malachi text, it becomes clear that a kind of

solar christology was developing which could be pointed in the same direction as

the cosmic piety represented by Sol Invictus. (see Strittmatter, pp. 614-617). .

. . What happened to December 25, however, is a good deal more than the

replacement of one sun-god or sun-festival with another. What was done was not

only to change a single holiday but rather to impose the essentials of an entire

Christian calendar on the Roman empire. (Kraabel 1982: 278)

At the same time, while

several early Christian leaders actively borrowed the traditional Roman mid-winter

ceremony to serve as the celebration of the birth of Christ, some expressed

concern regarding the incomplete separation of the two festivals.

Admonitions like those of

Augustine and Pope Leo had now clearly become necessary, for this deeply-rooted

pagan festival of the 'unconquered sun god' did not, in fact, simply disappear,

but persisted in many practices which passed over into the Christian festival.

So when Christmas was separated from another Christian festival, that of

Christ's baptism, it fell under the influence of a pagan one. At first this

influence was felt in Christian customs. We learn, for instance, from a Syrian

theologian that Christians also now began the practice of lighting bon fires on

this day.

(Cullmann 1956: 32)24

Pagan Romans

had also

introduced the mid-winter holiday of

Saturnalia

into the annual calendar, which was celebrated from December 17-25.

Throughout this celebration,

Roman courts were

closed, and Roman law dictated that no one could be punished for damaging

property or injuring people during the weeklong celebration. The festival began

when Roman authorities chose "an enemy of the Roman people" to represent the

"Lord of Misrule." Each Roman community selected a victim whom they forced

to indulge in food and other physical pleasures throughout the week. At

the festival's conclusion (December 25th), Roman authorities believed

they were destroying the forces of darkness by brutally murdering this innocent

man or woman.

(Judaism

Online).25

During the 4th

century, Christianity imported the Saturnalia festival in an effort to

convert the pagan masses. Christians had little success, however, in refining

the practices of Saturnalia. According to Nissenbaum (1997: 4),

In return for ensuring

massive observance of the anniversary of the Savior's birth by assigning it to

this resonant date, the Church for its part tacitly agreed to allow the holiday

to be celebrated more or less the way it had always been.

26

The scholarly consensus

today, then, is that the celebration of Jesus' birth was moved to

December 25th in order to both counteract and accommodate pagan

beliefs and practices, most notably the Roman celebration of the

Dies natalis solis invicti,

the annual ritual celebrating the rebirth of the Sun (the winter

solstice).

By

celebrating Jesus' birth on December 25th, and placing it within its holy

calendar, the Church effectively replaced and co-opted a pre-existing pagan

holiday that was embedded within the former Imperial Roman calendar. In the

process, the Church associated Jesus with a whole variety of attributes (most

notably his association with the sun, his representation of the victory of light

over darkness, and his purported miraculous birth) that had been attributed to

existing (and competing) pagan high gods, most notably Sol Invictus and Mithras, the most recent personifications of Imperial

Rome's paramount god. It is also clear that Church leaders were well aware of

the adaptations they were promoting.

Several

sources have over the centuries acknowledged that the Roman celebration of the birth of the sun

served as

the basis for choosing December 25th to commemorate the birth of Jesus. A note inserted into a manuscript written by the Syrian, Dionysius Bar-Salibi,

in the late 12th century (apparently by someone other than Dionysius)

offered the following explanation for why the Nativity is celebrated on December

25th.

The Lord was born in the

month of January, on the day on which we celebrate the Epiphany; for the

ancients observed the Nativity and the Epiphany on the same day. . . . The

reason for which the Fathers transferred the said solemnity from the sixth of

January to the twenty-fifth of December is, it is said, the following: it was

the custom of the pagans to celebrate on this same day of the twenty-fifth of

December the feast of the birth of the sun. To adorn the solemnity, they had the

custom of lighting fires and they invited even the Christian people to take part

in these rites. When, therefore, the Doctors noted that the Christians were won

over to this custom, they decided to celebrate the feast of the true birth on

this same day; the sixth of January they made to celebrate the Epiphany. They

have kept this custom until today with the rite of the lighted fire.

(see

Roll 2000: 280)

The Reverend Increase

Mather of Boston offered a similar explanation in 1687.

The early Christians who

first observed the Nativity on December 25 did not do so thinking that Christ

was born in that Month, but because the Heathens' Saturnalia was at that time

kept in Rome, and they were willing to have those Pagan Holidays metamorphosed

into Christian ones.

27

In

fact, it was its link to paganism, in particular the

celebratory excesses associated with the holiday,

that resulted in strong Puritan opposition to the celebration of Christmas.

In his

An Anatomie of Abuses

(1583), Phillip Stubbes, an

English Pamphleteer, wrote disapprovingly,

That more mischief

is

that time committed than in all the

year besides, what masking and mumming, whereby robbery whoredom, murder and

what not is committed? What dicing and carding, what eating and drinking, what

banquetting and feasting is

then used, more than in all

the year besides, to the great dishonour of God and impoverishing of the realm.

(Durston 1985: 8)

The observance of Christmas was

generally banned by the Puritans and was even made illegal in Massachusetts

between 1659 and 1681, due to its perceived pagan origins (see Kraabel 1982: 279; Nissenbaum 1987: 3). According to Kraabel (ibid.), classes were

not cancelled in Boston public schools on December 25th, and "any student staying home to celebrate Christmas was severely punished."

A second and equally

important basis for the deep-seated Puritan objection to the celebration of

Christmas was the holiday's association with the Roman Catholic

Church. In its First Book of Discipline,

published in 1561, the newly founded

Kirk ("Church") of Scotland rejected those holidays not present in the

Scriptures, which they considered "Papist" inventions. It listed Christmas among

the many

holy dayis of certane

Sanctis commandit by man, suche as be all those that the Papistis have invented

. . . [and which] . . . becaus in Goddis Scripturis thai nather have

commandiment nor assurance, we juge thame utterlie to be abolischet from this

Realme. (Laing 1846-64: 185-186; quoted in Nothaft 2011: 504)

The prolific Pamphleteer,

William Prynne (1633), also denounced Christmas as a Papist repackaging of

ancient Roman rites.

If

any here demaund, by whom these Saturnalia, these disorderly Christmasses &

Stageplayes were first

brought in

among the Christians? I answer that the paganizing Priests and Monks of popish

(the same with the heathen Rome) were the chiefe Agents of this worke.

(quoted in Nothaft 2011: 521)

The Puritan "War on

Christmas" (see Durston 1985, 1996) was

inextricably connected to the English Civil War (1642-1651), which pitted Protestants

against Catholics. According to Durston (1985: 8),

The celeb

ration

of Christmas thus became just

one facet of a deep religious cleavage within early seventeenth-century

England which, by the middle of the century, was to lead to the breakdown of

government, civil war and revolution.

When the Puritans took control of government in the mid-1640s they made a

concerted

effort to abolish the Christian festival of Christmas and to outlaw the

customs associated with it . . .

Western vs. Eastern Dates for the Nativity

Church leaders in the late 4th century had to employ

considerable pressure throughout the eastern empire to get Christians to celebrate

the birth of Jesus on December 25th.

Significant local opposition existed to the imposed date, due in large part to

the fact that the

Epiphany,

celebrated on January 6th,

already held a traditional place in the eastern liturgical calendar as the feast

of the Incarnation

(Roll 2000: 276). While John Chrysostom succeeded in establishing the December

25th date in Constantinople in 379, and shortly thereafter in Cappadocia and

Syria (Strittmatter 1942: 604), other churches throughout the eastern empire

resisted. Egypt (Alexandria) did not capitulate until 431.28

The Church in Palestine held out even longer; it was not until the middle of the

6th century that the Jerusalem Church abandoned its opposition to the December

25th date (Cullmann 1956: 33; Kraabel 1982: 277). The Armenian Church completely

refused to adopt the new date and continues to celebrate both the Nativity

and Baptism on January 6th.29

Significantly, the January 6th birth date was rationalized in the East using the same

theological arithmetic as was employed to justify the December 25th date in the West.

January 6th is 9 months after April 6th, which was in the East regarded as

the date of Jesus' conception and crucifixion (Cullmann 1956: 22).

The

celebration of Jesus' birth on January 6th long pre-dated that of December 25th.

The January 6th date was celebrated throughout the eastern empire, including in

Palestine, the very land where Jesus lived. The Gnostic followers of Basilides

were celebrating the birth of Jesus on January 6th as early as the 2nd

century, and likely before 160 (Kraabel 1982: 275). January 6th

was still being celebrated as Jesus' birth date in the mid-4th

century in Gaul and in Spain, and there is no evidence for the celebration of the

nativity on December 25th

in Gaul [present-day France]

before 400 (Strittmatter 1942: 609). According to Cullmann (1956:

25-26), an early 4th century Egyptian papyrus exists, which is "the oldest

Christmas liturgy we possess, and in

it Christmas is still observed on the night of January 5th-6th."

The papyrus contains the liturgical formula for a church choir celebrating the

feast of the Epiphany on January 5th-6th, the date when Jesus' baptism in the

Jordan was celebrated. However, a segment of the papyrus contains instructions

for that part of the festival celebrating Jesus' birth and includes an account

of the birth in Bethlehem, the flight to Egypt, and the return to Nazareth.

January

6th was, thus, celebrated quite differently

in the eastern and western churches. Whereas only the story of the star and the

visitation of the Magi was observed on that date by the Roman Church (Cullmann

1956: 26),30

Jesus' birth, his baptism, the visitation of the magi, and the wedding feast of

Cana were all celebrated on January 6th in the eastern church. At the same time, in

Gaul and Spain January 6th was the day to commemorate the Nativity, the Baptism,

and Miracle of Cana and even, at times, the Multiplication of Loaves and Fishes

(Kraabel 1982: 275). Furthermore, Strittmatter notes that, while the Roman mass

book for January 6th only celebrates the visitation of the Magi, the Baptism and

the Miracle of Cana are both mentioned in the

Breviary,

where Stanzas 8, 9, 11, & 12 of Sedulius' hymn,

A solis ortus cardine

sung at Vespers

concern the adoration of the Magi, the Baptism of Christ, and the miracle of

Cana (Strittmatter 1942: 626, note 93).31

The feast of the Epiphany was celebrated with

great splendor in Palestine. According to Cullmann (1956: 27-28),

The well-known account by

the noble pilgrim Aetheria (Egeria), who spent 3 years in Palestine.

*

She could not find words adequate to describe the magnificence of the of the

festival. She tells how all, along with the bishop, repair in solemn procession

to Bethlehem on the night of January 5th-6th in order to

hold a service at night in the cave where Jesus was supposed to have been born.

Before daybreak, the whole procession moved off to Jerusalem. As January 6th

dawns, they reach Jerusalem and enter the Church of the Resurrection, whose

interior is illuminated with thousands of candles. They depart the church and

reassemble by mid-day.

* Etherie, , "Sources

chretiennes," Journal de

Voyage. Paris 1948,

p. 203 ff.

Cullmann

(1956: 27) also notes that the Syrian

Church Father, Ephraem (306-373) called the January 5-th-6th

festival the most sublime of Christian festivals and stated that on the eve of

January 6th every house was decked with garlands. According to Cullmann (ibid.),

Ephraem rejoiced at the nocturnal festival.

"The

night is here" he says, "the night which has given peace to the

universe! Who would sleep on this night when the whole world is awake!"

According to

Ephraem, the evening festival celebrated the birth of Christ, including the

adoration of the shepherds and the appearance of the star, while the

following day was dedicated to the adoration of the magi and to the baptism

of Christ in the Jordan. (ibid.)

The whole creation

proclaims,

The Magi proclaim,

The star proclaims:

Behold, the king's son is here!

The heavens are opened,

The waters of Jordan sparkle,

The dove appears:

This is my beloved son!

An

important element in the conflict over

celebrating Jesus' birth on December 25th vs. January 6th concerned the issue of

when Christ became incarnate.

The Orthodox (Roman) view was that the human and the divine came together in

Jesus at his birth. Early Gnostics, on the other hand, believed that Christ first appeared on earth

at Jesus' baptism, which they celebrated as the

Epiphany,

from the Greek epihaneia

("appearing"). The feast originally had nothing to do with the birth of Jesus as

told in the gospels of Matthew and Luke, but rather relied on Mark's gospel in

which the divine spirit first enters Jesus at his baptism (Mark 1: 10-11).32

The notion that Christ "appeared" instead of

being born was a widespread belief among early Christians. Gnostic Christian

texts virtually eliminated any belief in a human origin for Jesus. For Gnostics,

Christ was a spirit who inhabited a human body, not the body itself. It is also

significant that no birth story exists in the

Gospel of John,

which states simply, "In the beginning was the

Word . . . And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us"

(see John 1: 1-14). Similarly, in the second-century

Protevangelium of James,

the infant Jesus first appears in a bright cloud.

And they stood in the place

of the cave,

and behold a luminous cloud overshadowed the cave. And the midwife

said: My soul has been magnified this day, because mine eyes have seen strange

things -- because salvation has been brought forth to Israel. immediately the

cloud disappeared out of the cave, and a great light shone in the cave, so that

the eyes could not bear it. And in a little that light gradually decreased,

until the infant appeared, and went and took the breast from His mother Mary.

And the midwife cried out, and said: This is a great day to me, because I have

seen this strange sight. And the midwife went forth out of the cave, and Salome

met her. And she said to her: Salome, Salome, I have a strange sight to relate

to thee: a virgin has brought forth -- a thing which her nature admits not of.

(Protevangelium

of James:

19)33

Gnostic belief in the exclusive spirituality of Jesus' existence (

Docetism)

led many Gnostic Christians to adopt the Egyptian god Osiris' birth as a model

for the birth of Jesus. Osiris' birth was

celebrated on January 6 and was marked by a heavenly voice crying,

"The Lord of all comes forth

into the light"

(Plutarch. ls.et Os.

355 E.; quoted in Kraabel 1982: 275).

Hippolytus reported on Basilides' version of the Christmas story,

The light came down from the

Seven upon Jesus the son of Mary, and he was illuminated and set on fire by

the light which shown upon him.

(ibid.)

This belief stood in direct conflict with the

Imperial Roman Church, which fought against

Arianism,

Nestorianism,

Gnosticism

and all other forms of docetism. At the

Council of Nicaea

(325), the Church established Jesus' humanity as canonical, declared any form of

Docetism as heretical, and expressly denounced any doctrine which denied that

Jesus became incarnate at his birth. The

Council of Constantinople

(381) reaffirmed the declarations made at Nicaea and established as canonical

the Trinitarian

doctrine proclaiming the equality

of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, finalizing the Church's doctrinal position

on the humanity of Jesus.34

The

January 6th date had other precedents in pagan ritual. As previously discussed,

early Christians associated Jesus with the sun and with the bringing of light to

the world (cf. Matt 5: 14; John

8: 12, 9: 5, 11: 9; 2 Corinthians 4: 4). This

facilitated Jesus' replacement of Sol/Mithras in the December 25th nativity

celebration in Rome. The concept of

light played a central role in the celebration of Jesus' birth on January 6th as

well. A feast of Dionysus (son of Zeus), associated

with the lengthening of the day was celebrated on January 6th

(Cullmann 1956: 25). January 6th was

also the date on which the lengthening of the days was celebrated by pagans in

Alexandria at the birth of Aeon

to the maiden, Kore (Cullmann 1956: 28). Strittmatter (1942: 618-619) describes

in detail an Egyptian ceremony honoring the virgin birth of Aeon on this date

and indicates that similar celebrations took place elsewhere, including at Petra

and Elousa.

In

addition, on the night before January 6th the waters of the Nile were

believed to possess special miraculous powers (Cullmann 1956: 25).

Strittmatter (1942: 621-623) states

that Pagans, Christians and Jews all celebrated January 6th with a

ritual dedicated to its "Magical Water." Plutarch linked this ritual to the cult

of Osiris. Both Pliny the Elder, and Pausanias describe a fountain in the temple

of Dionysus on the island of Andros from which wine gushed forth on the feast of

the god on the Nones

(the 5th of January). Epiphanius, the bishop of Salamis, Cyprus (365-403) and a

native of Palestine, claimed that the ritual celebrated the miracle of Cana in

which Jesus changed water into wine. John Chrysostom, on the other hand, asserted that it

commemorated Jesus' baptism, which by

"His descent into the Jordan, Christ hallowed

the waters." The fact that

Epiphanius and Chrysostom offered conflicting explanations of the same ritual

suggests the ritual pre-dated its Christian application. The ritual's

pre-Christian origin is further suggested by the fact that the blessing of the

waters, which was to become such a conspicuous feature of the liturgy of this

feast, is not mentioned by any Christian writer before the fourth century (ibid.).

By

choosing January 6th to celebrate several significant events in the life of

Jesus, most notably his birth, the Egyptian Church gained the same result as that

achieved by the Roman Church through its celebration of Jesus' birth on December 25th.

It co-opted and replaced an important and deeply embedded

pagan festival in order to promote Jesus as the new universal god. The only

difference is that, because the Roman

and Alexandrian churches had

to accommodate distinct pre-existing pagan beliefs and practices in

their respective regions, the Roman Church celebrated

Jesus' birth on December 25th, while the Egyptian Church commemorated it on

January 6th.

The

celebration of different dates for the birth of Jesus became one of the

doctrinal issues

that divided the early Church. The

Roman Church had a theological need to separate the Nativity from the Epiphany;

by enforcing the December 25th date, the Roman Church not only co-opted a Roman pagan festival,

it also negated the legitimacy of the January 6th celebrations and, by

extension, the authority of the Alexandria Church, which led the opposition to

the Roman Church's quest for political and ecclesiastical hegemony (see Baynes

1926; Hardy 1946). Many Christian communities fought the imposition of Roman

orthodoxy, causing major rifts within

the Church, one part of which involved the

celebration of Jesus' birth.35

These rifts resulted in substantial, frequently violent conflicts between

competing Christian communities, especially during the fourth and fifth

centuries. Numerous

sources examine the political conflict that raged among competing factions

in the early Church and the extent to which that competition resulted in

violent confrontations and the calling of ecumenical councils by opposing

factions in order to counter the rulings of councils called by their opponents.

(see Baynes 1926; Bauer 1934;

Jones 1959; Betz 1965;

Frend 1972; Grant 1975; Gregory 1979;

Jenkins 2011; Palmer 2014).

Several sources specifically examine the conflict between the

Eastern Church (led by Alexandria) and the Western Church, centered initially in Rome and later

in Constantinople (see Baynes 1926; Hardy 1946; Haas 1991; Jenkins 2011: passim).

Bart Ehrman (1993) provides a skillful analysis of how the theological

controversies that plagued the early Church resulted in the Roman (Orthodox)

Church altering the original meanings of several New Testament texts to more

closely support its theology over that of competing factions within the

Church, "corruptions" that have survived to the present day as canonical New

Testament scripture.

As

indicated, a significant focus of this conflict

centered around the competition between the patriarchates of Alexandria and Constantinople, which served as the principal representatives for Eastern and Western

Christianity respectively (Baynes 1926; Hardy 1946; MacCulloch

2009: 215-240).36

The Egyptian Church was the leader of the monophysite faction in the

monophysite-miaphysite controversy37

that divided the Church into frequently violent, mutually opposing factions during the 5th century.

Murder, assassination and clergy-led mob violence were all part of the

turbulence that characterized the 5th century (see Frend 1972). In this

ecclesiastical conflict, monophysitism served as a fundamental ideological identifier of Egyptian

opposition to Roman rule. Conflict over competing dates for the birth of Christ

would have been subsumed within this larger theological debate, and as the

Western (Roman) Church defeated the Eastern Church for supremacy within the

empire, its dating of Jesus' birth won out over that promoted by the Egyptian

Church. The Third Canon

of the Council of Constantinople

(360) had raised the see at Constantinople to the second position in the Church,

after that of Rome, since Constantinople was now the "new Rome", i.e., the new

capital of the empire. The intensity of the conflict between the two competing

patriarchs (Chrysostom and Theophilus) reached such a peak that both attempted

to have the other declared a heretic.

The

Council of Chalcedon (451),

marked the final victory for the patriarch of Constantinople over Alexandria,

and thus the supremacy of the Western Church and its theology. Dioscorus, the

existing Patriarch of Alexandria, was deposed by the Council and replaced by

Proterius, chosen by Constantinople. This victory of Constantinople and its

theology produced a violent reaction in Alexandria.

Nothing could secure the real