.jpg)

Christ in the Mystic Winepress

.jpg)

William S. Abruzzi

(2021)

Christ in the Mystic Winepress was a popular Christian motif during the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. It was based on eschatological interpretations of passages in Isaiah and the Book of Revelation, as well as on Catholic belief in the redemptive power of Christ's blood. The winepress motif was one of the few Catholic teachings that survived the Protestant Reformation. However, while Catholic theologians emphasized the winepress as representing Christ's Passion and suffering, Protestant theologians placed greater emphasis on the winepress as expressing Christ's triumph over evil. While the Christ in the Winepress image has largely disappeared from Christian art and theology, the concept of the winepress has continued to serve as a powerful literary metaphor.

Monk Gibbon (1957: 113) describes a unique chapel that he visited while traveling in the Rhineland region of Germany with his young daughter. The chapel lay largely hidden in the woods high on the hill above the village of Ediger-Eller on the Moselle River, a tributary to the Rhine.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The chapel dates to around 1500 and has served as a pilgrimage site for several centuries. The path leading to the chapel from the village below contains fourteen petite pylons showing Jesus' Stations of the Cross.

|

|

|

Today, a wooden sign directs travelers to the chapel from the road on top of the hill.

|

|

CrossChapel Christ in the Winepress |

The first thing one sees upon entering the chapel is a relief of Jesus adjacent to a cross being pressed down on him by a large screw at the center of a winepress. Blood flows from Christ's wounds into the basin below to form the wine that will eventually be used in the sacrament of The Eucharist (Holy Communion).1 The whole scene is framed by a quote taken from Isaiah (63:3).

"I have trodden the winepress alone;

and from the peoples no one was with me.

I trod them in my anger

and trampled them in my wrath;

their lifeblood is sprinkled upon my garments,

and I have stained all my raiment."

What was a captivating discovery for Gibbon and his daughter is but one example of what was once a popular and widespread motif in Western Christianity. Images of Christ in the Mystic Winepress (CMW) were ubiquitous throughout much of Europe during the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. While most known images are dated from the 14th to 17th centuries, CMW representations were produced as early as the 12th century and as late as the 18th century and have been found throughout the European continent, including in Germany, France, Italy, Romania, the Netherlands, Poland, the Czech Republic, Austria, Belgium and Denmark. The CMW image was notably one of the few Catholic sacred icons retained by Protestant denominations following the Reformation.

Although CMW images have been found throughout much of Europe, they are most heavily concentrated in northern Europe, in particular in Germany and the Netherlands, where the mechanical winepress was used in the production of wine (Duffy 2017: 3). CMW images are largely absent in Great Britain (Defoer 1980: 139), where wine production was not widespread. Such images are also less common in southern Europe, including in such wine producing countries as Italy and Spain.2 However, despite being major centers of wine production, the "basket" winepress, which served as the model for the Christological winepress, was not in widespread use in these countries.3

Basket Wine Presses

Hessen, Germany

Kloster Eberbach

The CMW image even spread to the New World, illustrated by the following two 18th century paintings, one located in Mexico, the other in Argentina. Both paintings are based on a 17th century Flemish print by Hieronymous Wierix (presented later).

|

The Mystic Vintage (a.k.a. Christ of the Redemption) Chiapas, Mexico Chapel of El Calvario

|

Mystic Winepress (unknown Cuzco artist) (18th century) Ciudad de Córdoba, Argentina Museo de Arte Religioso Juan de Tejeda,

|

All surviving CMW images, save one, show Jesus pressing red grapes, which would be consistent with the grapes representing Jesus’ blood (see discussion below). The sole exception comes from Kuttenberg, Germany, a region where green grapes have been widely grown to produce white wine.

.jpg)

Christus in der Kelter

(c.1490)

Kuttenberg, Germany

Kuttenberger Kantionale

CMW images were produced through a variety of mediums, including paintings, prints made from engraving, tapestries, stained glass and manuscript illustrations.

Paintings were the most common form through which the CMW image found expression.

|

Christ in the Winepress c. 1400-1450 (German) Karneid, Italy Karneid Castle Chapel |

untitled

(1460-1470) Paris Musee du Louvre |

|

Hildesheim Miniature 16th century (Netherlands) Washington, DC National Gallery of Art

|

Khristos in a Grindstone (17th century) Kiev, Ukraine National Art Museum |

|

Christ in the Winepress (c. 1430-1440) Krakow Church of St. Francis of Assisi

|

Christ in Glory above the Mystic Winepress (c. 1571) Vatican Pinacoteca |

Christ in Mystic Winepress

1550-1600

Milan

Santa Maria Incoronata Church

CMW Images also appear on stained-glass windows.

|

Mystic Winepress (1552) Conches en Ouche Eglise de Sainte-Foy

|

The Mystical Winepress Linard Gontier (1625-28) Troyes, France Saint-Pierre-Saint-Paul Cathedral, |

Pressoir Mystique

(1618)

Paris

Saint Etienne-du-Mont

The center of the above window (mid-section enlarged below) contains an unusual form of press in which Jesus is lying prostrate within the press with the blood flowing from his wounds and through a spout. The foreground of the entire window shows St. Peter, as the primary apostle, treading grapes in a circular tub to the left of Jesus. with angels and apostles transferring the blood of Christ being stored in barrels by both secular and ecclesiastical authorities.

.jpg)

They can also be found on church altars.4

.jpg)

2.jpg)

Jesuit Church of the Annunciation

(c. 1740)

Mindelheim, Germany

.jpg)

Subsidiary Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary

(c. 1566)

Oberwittelsbach, Germany

|

|

Salvator Church High Altar (c. 1463) Bogenberg, Germany

|

CMW images were especially common in various types of manuscripts, including bibles and books of hours.

Probably the earliest manuscript representation of Christ in the Mystic Winepress is the Hortus Deliciarum, a 12th-century illustrated encyclopedia compiled by the abbess Herrad von Landsberg at the Hohenburg Abbey in Alsace, which was prepared as an instructional manual for the nuns in her abbey. The manuscript is noted for the distinction of its 336 illustrations. It provides an account of salvation history beginning with Christ pressing the grapes and ending with the peace and salvation to follow the last judgment and the death of the Antichrist. In his examination of the "Antichrist Cycle" presented within the manuscript, Campbell (2015: 87) notes the importance of it beginning with an image of Christ treading the winepress.

Thus, as the Hortus moves in its presentation of salvation history from an extended section of texts on the Church, the contemporary institution and propagator of God's historical plan (fols. 225v-240v), to its eschatological presentation of the last four things --death, judgment, heaven and hell-- it is with the story of the Antichrist that Herrad begins. On the page across from the dove of the Church on fol. 240v is the image of Christ treading the Mystic Winepress, presented within a circular frame. While the context is still ecclesiastical, the image resonates with the apocalyptic image of Christ treading "the winepress of the fierceness of the wrath of God the Almighty" . . . .

.jpg)

Mystic Winepress

Hortus Deliciarum of Herrad of Hohenbourg

(late 12th century)

Paris

Bibliothèque nationale de France

(Campbell 2015: 89)

The eschatological interpretation of Christ treading the winepress is further noted in the above image by the figures of Enoch and Elijah preaching to a group of people (including two Jews identifiable by their tall pointed hats) in the lower right, "in the furthest parts of the vineyard as if at the end of the world" (Campbell 2015: 102). In addition, on the lower left Christ is reaching out to an individual standing outside the circle who an inscription identifies as a "healed leper, that is, converted sinner." (Campbell 2015: 102, note 75) Referencing Griffiths (2007: 202-203), Campbell notes that at several points Herrad links leprosy with avarice and simony. In its portrayal of the Last Judgment, Revelation (14:19-20), proclaims that those living outside the city, i.e., outside the Christian community represented here by the circle, are those whose blood will be shed in "the great wine press of the wrath of God".

.jpg)

Bible Moralisee de Philippe le Hardi

(c. 1485-1493)

(Provence)

Paris

BIbliotheque Nationale de France

Bible Moralisée is a later name given to Medieval picture bibles made in thirteenth-century France and Spain. Selected Bible stories were told using texts, illustrations and commentaries on the moral significance of each story. These books were among the most expensive medieval manuscripts ever made because of their large number of illustrations. (see Bible Moralisée of the Thirteenth Century).

Commentary on the Fourth Gospel

Nicholas of Lyra

(c. 1400-1410)Vienna

Österreichischen Nationalbiliothek

|

Allegory of the Sacraments (16th century) Colmar, France Bibliotheque Municipal

|

Christ Treading the Winepress (Netherlands) (c. 1405-1410) New York Pierpont Morgan Library |

The Book of Hours was a popular medieval Christian devotional book developed for lay people who wished to incorporate monastic elements into their religious life. Reciting the hours typically centered on the reading of psalms and other prayers. These books were referred to as a "Book of Hours" because they were to be read and recited daily during the seven canonical hours. Several thousand Books of Hours have survived to the present. These books are generally beautifully illustrated, and many contain illustrations depicting Christ in the Mystic Winepress.

|

Ego Sum Pastor (I am a Shepherd) Bonus Book of Hours Tournai, Belgium (16th century) New York Pierpont Morgan Library

|

Christus in der Kelter

Hours of Ulrich von Montfort

(c.1515-1520)

Vienna

Oesterreichische Nationalbitliothek

|

|

|

Fons Vitae (The Savior Adored by Saint Catherine of Alexandria and a Female Donor) (1535) (From a Book of Hours) Tournai, Belgium (Flemish) The Hague Koninklijk Bibliotheek (Duffy 2017: 19)

|

|

|

Hours of Catherine of Cleves

(Utrecht)

(c.

1435-1445)

New York

Pierpont Morgan Library

|

According to Gertzman (2013: 315-316), in the two portraits of Christ on the above page from the Hours of Catherine of Cleves,

Christ is figured as his own doppleganger: stepping atop a precariously balanced cross and displaying his wounds in the upper miniature, and, in the lower margin, bleeding even more profusely from numerous lacerations into the trough of the press. Blood, which finally gathers in the chalice, is underscored by the presence of the scourge and the reed held under Christ’s limp arms.

Prints containing CMW images were also produced for commercial distribution.

|

Christ in the Winepress Hieronymous Wierix (Antwerp) (before 1619) New York Metropolitan Museum of Art

This print served as the model for the 18th century CMW images in Mexico and Argentina shown above. |

The Fall and Salvation of Mankind, Christ in the Winepress

Anonymous after Maarten van Heemskerck

(Netherlands) (1568) London British Museum

|

-Museum%20Boijmans%20Van%20Beuningen.aspXt_in_winepress.jpg)

Title Print of Passion Series

Jacques de Gheyn

(1596)

Rotterdam

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

|

Le Pressoir Mystique Jean d'Intas (1609) Paris Bibliotheque Nationale de France

|

Christ in the Wine Press Hieronymus Wierix (Flemish) (before 1619) London British Museum |

CMW images can also be found on tapestries,

|

Mystic Winepress South Netherlandish (c. 1500) New York Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

Embroidered Antependium (1644) Kortrijk, Belgium Church of St. Martin

|

. . . gravestones,

|

Heilig-Geist-Hospital (1491) Lübeck, Germany

|

Bartold Busse Deceased (10-10-1522) Hannover, Germany Nikolaikapelle (St. Nicholas' Chapel) |

. . . and clay molds.

|

Christ in The Winepress (tile mold) (c. 1430-1470) Berlin Museum of Decorative Arts

|

Christus in der Kelter (mid-15th century)

|

Christ in the Winepress

(c. 1450)

Terracotta mold

(Rhineland)

London

Victoria and Albert Museum

In the above clay moulds, an angel can be seen operating the press, while Jesus himself is turning the screw. In addition, the verse from Isaiah (63:3) appears on the banderole emerging from Jesus' mouth, making them his words. The kneeling figure, probably the Virgin is shown praying, while God the Father overlooks the scene from among the stars above. Moulds such as these were primarily used for making pastries for the special feast days of the Christian year, but were also used to make cheap metal reliefs to serve as pilgrimage badges and for decorating bells and mortars in bronze foundries (Llobet and Famadas 2019: 42; Victoria and Albert Museum: #C.329&A-1926).

Biblical Origin of the Winepress Motif

The Christian concept of the Mystical Winepress finds its origin in the Bible, both in the Old and New Testaments. While several passages provide biblical support for the tradition of Christ in the Mystic Winepress, two documents stand out both in their theological importance and in the frequency of their citation: Isaiah in the Old Testament and Revelation in the New Testament.

Isaiah 63:3

"I have trodden the wine press alone,

and from the peoples no one was with me;

I trod them in my anger

and trampled them in my wrath;

their lifeblood is sprinkled upon my garments,

and I have stained all my raiment.

Revelation 14:19-20

So the angel swung his sickle on the earth and gathered the vintage of the earth, and threw it into the great wine press of the wrath of God; and the wine press was trodden outside the city, and blood flowed from the wine press . . . .

Revelation 19:15-16

From his mouth issues a sharp sword with which to smite the nations, and he will rule them with a rod of iron; he will tread the wine press of the fury of the wrath of God the Almighty. On his robe and on his thigh he has a name inscribed, King of kings and Lord of lords.

The above two documents serve as reference points for the two principal CMW images (to be discussed below): Christ as the Man of Sorrows suffering for the sins of mankind, and the Triumphant Christ conquering sin and evil.

Isaiah lived in Jerusalem (in Judah) in the 8th century BCE during the last years of the northern kingdom (Israel). Scholars divide the Book of Isaiah into three parts, only the first of which (Chapters 1-39) is attributed to Isaiah himself and to his contemporary followers.

Second Isaiah (Deutero-Isiah - Chapters 40-55) is generally attributed to members of a "school" of Isaians that existed in Babylon during the Babylonian Captivity and is thought to have been written about the time of the conquest of Babylon in 539 BCE by Cyrus the Great of Persia, after which the exiled Jews were permitted to return to their homeland. Third Isaiah (Trito-Isaiah - Chapters 56-66), including the passage above containing the reference to treading the winepress, is considered to have been written following that return to Jerusalem in 538 BCE. The canonical Book of Isaiah, with its editorial redaction, is generally believed to have come into its present form sometime during the fourth century BCE.

Understanding the passages taken from Isaiah, therefore, requires a recognition of the historical context in which its different parts were written. The oracles of Isaiah presented during his early ministry (c. 740-732 BCE) rebuke the nation of Judah for its many sins and claim that its troubles were the result of God's punishment for the people of Judah not living up to his laws. Isaiah called on them to honor Yahweh and to have faith in him, for he will send a savior to free them from outside domination. It is in this context, during the Syro-Ephraimitic War (734-732 BCE) in which Syria and Israel joined forces against Judah that Isaiah prophesied the coming of a savior who would free Judah from external conquest. Believing Assyria would eventually eliminate the threat to Judah posed by the northern kingdom of Israel, Isaiah made his famous prophecy that Yahweh would give King Ahaz a sign: "Behold, a young woman shall conceive and bear a son, and shall call his name Emmanuel." ["God is with us"] (Isaiah 7:14). This child would become the Messiah to free Judah from its oppressors. This quote has subsequently been interpreted by Christians, not as reference to the events occurring during Isaiah's lifetime, but as a prophecy predicting the birth of Jesus some eight centuries later.5

The passage quoted above from Isaiah referring to the treading of the winepress is, like that of Isaiah 7:14, taken out of its historical context and applied by Christians to Jesus. Third Isaiah was composed during the closing years of the 6th to the middle of the 5th century BCE, following the return of Jews to their homeland with the end of the Babylonian Exile. That conquest and servitude was attributed by Isaiah to the sins of Judah and its people (see Isaiah 57-59). In Isaiah 62, God announces Judah's coming salvation (political not spiritual) and the rejuvenation of Jerusalem through his defeat of the nations that oppress them. Prominent among these was the Kingdom of Edom immediately to the south of Judah, with its capitol at Bozrah. In Chapter 63:1-6, God spells out how he will accomplish Judah's salvation. When the question is posed, "Who is this that comes from Edom, in crimsoned garments from Bozrah, he that is glorious in his apparel, marching in the greatness of his strength? God responds, "It is I, announcing vindication, mighty to save." When asked, "Why is thy apparel red, and thy garments like his that treads the wine press?", God replies,

I have trodden the wine press alone,

and from the peoples no one was with me;

I trod them in my anger

and trampled them in my wrath;

their lifeblood is sprinkled upon my garments,

and I have stained all my raiment.

For the day of vengeance was in my heart,

and my year of redemption has come.

I looked, but there was no one to help;

I was appalled, but there was no one to uphold;

so my own arm brought me victory,

and my wrath upheld me.

I trod down the peoples in my anger,

I made them drunk in my wrath,

and I poured out their lifeblood on the earth.6

The complete quote makes the meaning of the passage clear; God has not forgotten Judah, nor Jerusalem. He is coming back to establish his kingdom, and Jerusalem will be its capital. The reference is to events in the 6th century BCE, not to the end of days when a final judgment of humankind will purportedly take place.

The historical basis of the above passage is reinforced by the fact that it is the third time the winepress motif is used in relation to Judah's fate. An earlier use of the same motif is contained in a theological explanation for the very destruction of Jerusalem and conquest of the Kingdom of Judah that resulted in the exile of thousands of Jews to Babylonia in the first place (see Lamentations 1:1-15).

Jerusalem's fall from grace is expressed in Lamentations 1:1.

How lonely sits the city

that was full of people!

How like a widow has she become,

she that was great among the nations!

She that was a princess among the cities

has become a vassal.

In the five books of Lamentations, the destruction of Jerusalem is attributed to God's punishment for the sins of the nation, as is expressed in Lamentations 1:8.

Jerusalem sinned grievously,

therefore she became filthy;

all who honored her despise her,

for they have seen her nakedness;

yea, she herself groans,

and turns her face away.

And God's role in Judah's downfall, using the winepress as the metaphor for his vengeance, is made clear in Lamentations 1:15.

The Lord flouted all my mighty men

in the midst of me;

he summoned an assembly against me

to crush my young men;

the Lord has trodden as in a wine press

the virgin daughter of Judah.

The winepress as an act of vengeance also figured prominently in the Book of Joel. Joel was one of the minor pre-exilic prophets. He preached that salvation would come to Judah and to Jerusalem only when the people turned to Yahweh. Following his lament over the destruction of Judah by a plague of locusts, Joel claimed the attacking locusts and the drought that followed were the first signs that the feared "Day of the Lord" was near, a day of dreaded judgment (2:1-10). On the Day of the Lord, Joel asserts, the Lord will judge the nations of the world, including the Children of Israel. Later, following proclamations of fire, destruction and desolation, Joel (2:18) states that God had pity on his people because they have returned to him and he makes them a promise: There will continue to be judgment against those nations that had warred against Judah.

I will remove the northerner far from you,

and drive him into a parched and desolate land,

his front into the eastern sea,

and his rear into the western sea;

the stench and foul smell of him will rise,

for he has done great things.

(Joel 2:20).

Later, he tells the Judeans to

Proclaim this among the nations:

Prepare war,

stir up the mighty men.

Let all the men of war draw near,

let them come up.

Beat your plowshares into swords,

and your pruning hooks into spears;

let the weak say, "I am a warrior."

(Joel 3:9-10)

And adds:

Let the nations bestir themselves,

and come up to the valley of Jehosh′aphat;

for there I will sit to judge

all the nations round about.

Put in the sickle,

for the harvest is ripe.

Go in, tread,

for the wine press is full.

The vats overflow,

for their wickedness is great.

(Joel 3:12-13)

For Christians, Isaiah 63:3 takes on a new meaning. In the Christian interpretation, Yahweh is replaced by Christ, his vengeance becomes pity; and the blood of those stricken becomes the blood of Christ himself (see Gertzman 2015: 311-312). This is the source of the Man of Sorrows theme associated with the CMW motif.

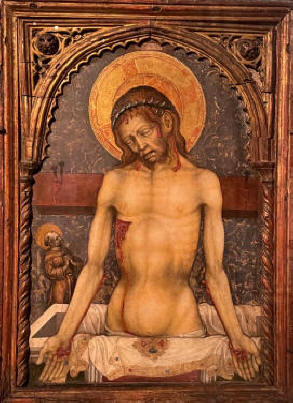

The Man of Sorrows

Michele Giambono

(c. 1430)

New York

Metropolitan Museum of Art

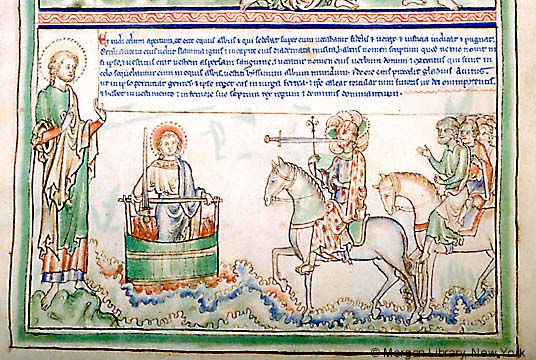

The retribution theme is expressed most forcefully later in the Book of Revelation.

From his mouth issues a sharp sword with which to smite the nations, and he will rule them with a rod of iron; he will tread the wine press of the fury of the wrath of God the Almighty. On his robe and on his thigh he has a name inscribed, King of kings and Lord of lords.

(Revelation 19:15-16)

The earliest Christian (post-Old Testament) use of the winepress motif occurs in the Book of Revelation, first in Revelation 14:14-20 (Reaping the Earth's Harvest):

Then I looked, and lo, a white cloud, and seated on the cloud one like a son of man, with a golden crown on his head, and a sharp sickle in his hand.

And another angel came out of the temple, calling with a loud voice to him who sat upon the cloud, "Put in your sickle, and reap, for the hour to reap has come, for the harvest of the earth is fully ripe." So he who sat upon the cloud swung his sickle on the earth, and the earth was reaped. And another angel came out of the temple in heaven, and he too had a sharp sickle. Then another angel came out from the altar, the angel who has power over fire, and he called with a loud voice to him who had the sharp sickle, "Put in your sickle, and gather the clusters of the vine of the earth, for its grapes are ripe." So the angel swung his sickle on the earth and gathered the vintage of the earth, and threw it into the great wine press of the wrath of God; and the wine press was trodden outside the city,7 and blood flowed from the wine press, as high as a horse’s bridle, for one thousand six hundred stadia.8

The reaping of the Harvest, according to Revelation, will take place in two stages. First will occur the "harvest of the earth", i.e., the "ingathering of the Good". This will be followed by the "gathering of the vintage", which represents the crushing of the Wicked. It is the Vintage that will be thrown into "the great wine press of the wrath of God" and whose blood will cover the earth, and it is clearly Christ, the "son of man", who treads the winepress. A similar distinction between the final harvest of good and evil, though without the winepress, is presented in Matthew 13:36-43.

Then he left the crowds and went into the house. And his disciples came to him, saying, "Explain to us the parable of the weeds of the field." He answered, "He who sows the good seed is the Son of man; the field is the world, and the good seed means the sons of the kingdom; the weeds are the sons of the evil one, and the enemy who sowed them is the devil; the harvest is the close of the age, and the reapers are angels. Just as the weeds are gathered and burned with fire, so will it be at the close of the age. The Son of man will send his angels, and they will gather out of his kingdom all causes of sin and all evildoers, and throw them into the furnace of fire; there men will weep and gnash their teeth. Then the righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father. He who has ears, let him hear.

The treading of the winepress in the final judgment is again expressed in Revelation 19:11-16 (The Rider on the White Horse):

Then I saw heaven opened, and behold, a white horse! He who sat upon it is called Faithful and True, and in righteousness he judges and makes war. His eyes are like a flame of fire, and on his head are many diadems; and he has a name inscribed which no one knows but himself. He is clad in a robe dipped in blood, and the name by which he is called is The Word of God.9 And the armies of heaven, arrayed in fine linen, white and pure, followed him on white horses. From his mouth issues a sharp sword with which to smite the nations, and he will rule them with a rod of iron; he will tread the wine press of the fury of the wrath of God the Almighty. On his robe and on his thigh he has a name inscribed, King of kings and Lord of lords.

Apocalypse: Christ, Armies of Heaven

(c. 1255-1260)

(London)

New York

Pierpont Morgan Library10

The treading of the winepress as a symbol of the destruction and defeat of one's enemies derives in part from the use of the phrase "under feet" to express dominance over other things and/or conquest of enemies. Speaking of Christ's final return (1 Corinthians 15:24-27), Paul, for example, states,

Then comes the end, when he delivers the kingdom to God the Father after destroying every rule and every authority and power.

For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. The last enemy to be destroyed is death. For He has put all things in subjection under his feet.

A similar use of the phrase can be found elsewhere in both the Old and New Testaments.

Psalm 8:4-8:

what is man that thou art mindful of him,

and the son of man that thou dost care for him?

Yet thou hast made him little less than God,

and dost crown him with glory and honor.

Thou hast given him dominion over the works of thy hands;

thou hast put all things under his feet,

all sheep and oxen,

and also the beasts of the field,

the birds of the air, and the fish of the sea,

Psalm 47:2-4:

For the Lord, the Most High, is terrible,

a great king over all the earth.

He subdued peoples under us,

and nations under our feet.

Matthew 22:44:

The Lord said to my Lord,

Sit at my right hand,

till I put thy enemies under thy feet?

Romans 16:20:

then the God of peace will soon crush Satan under your feet.

Early Church Use of the CMW Motif

Several early Church leaders made reference to Christ treading the winepress, including Justin Martyr, Eusebius, Tertullian, Origen, St. Cyprian, St. Athanasius, St. Bonaventure and St. Jerome. (see Engel 1980: 47-48). Pope Gregory the Great (c. 560-604) commented on it, explicitly, drawing attention to the paradox of Christ both treading the winepress and being trod by it.

He has trodden the winepress alone in which he was himself pressed, for with his own strength he patiently overcame suffering. (Pope Gregory I; quoted in Schiller 1972: 228)

Perhaps the most notable of early Church leaders to comment on the winepress motif, and the one who most clearly influenced its subsequent interpretation, was St. Augustine (354-430). Augustine's commentary on the winepress motif was largely contained within his Exposition on the Book of Psalms. Augustine expanded Justin Martyr's interpretation of the man treading the winepress in Isaiah as the bloodstained and crucified Christ singly treading out the vintage (evil) for those whom he redeemed with his death. While Augustine accepted Justin's interpretation, he added the notion of Jesus as the bruised and crushed grape-cluster rather than the grape-treader. In Augustine's interpretation, Jesus is likened to the "grapes prepared for the winepress, his skin flayed and his body wrung out upon the cross" (see Hillier 2008: 391).11

Augustine also drew a connection between the winepress of Christ's Passion and the grape-cluster brought back by the spies Moses sent to reconnoiter the Promised Land (see Numbers 13).

There is another interpretation concerning the wine-presses, yet still keeping to the meaning of Churches. For even the Divine Word may be understood by the grape: for the Lord even has been called a Cluster of grapes; which they that were sent before by the people of Israel brought from the land of promise hanging on a staff, crucified as it were. (Exposition on Psalm 8.2)

|

Israelite Spies Carrying Grapes on a Pole12 Nicholas Verdun (1181) Klosterneuburg, Germany Augustinian Monastery

|

Joshua and Caleb Carrying the Grapes from the Eshkol Brook (1160–1170 ) London British Museum.

|

For Augustine, the winepress became the central symbol of the sacrifice that all Christians must endure to be true Christians. Just as Christ had been the first to tread the winepress, and only through that experience (his crucifixion) could the wine (the hope of salvation) have been produced, so also does every Christian need to tread their own winepress in order to earn their salvation. An unpressed grape, according to Augustine, remains barren; it is only through the pressing of the grape (suffering in the name of Christ) that the wine (salvation) is produced.

A grape on the vine sustains no pressing, whole it seems, but nothing thence flows: it is thrown into a winepress, is trodden, is pressed; harm seems to be done to the grape, but this harm is not barren; nay, if no harm had been applied, barren it would have remained. . . . The first cluster in the wine vat pressed is Christ. When that cluster by passion was pressed out, there flowed that whence "the cup inebriating is now passing beautiful!" . . . If therefore you suffer not any persecution for Christ, take heed lest not yet you have begun godly to live in Christ. But when you have begun godly to live in Christ, you have entered into the winepress; make ready yourself for pressings: but be not thou dry, lest from the pressing nothing go forth. (Augustine, Exposition on Psalm 56.3-4)

Augustine also taught that the Church functioned as a winepress, through which good people, aided by the work of God's ministers, are sifted out from the crowd of worldly people --i.e., those more concerned with material values than with spiritual ones-- living among them.

We may then take wine-presses to be Churches, on the same principle by which we understand also by a threshing-floor the Church

. For whether in the threshing-floor, or in the wine-press, there is nothing else done but the clearing the produce of its covering; which is necessary, both for its first growth and increase, and arrival at the maturity either of the harvest or the vintage. Of these coverings or supporters then; that is, of chaff, on the threshing-floor, the grain; and of husks, in the presses, the wine is stripped: as in the Churches, from the multitude of worldly men, which is collected together with the good, for whose birth and adaptating to the divine word that multitude was necessary, this is effected, that by spiritual love they be separated through the operation of God's ministers. For now so it is that the good are, for a time, separated from the bad, not in space, but in affection: although they have converse together in the Churches, as far as respects bodily presence. (Augustine, Exposition on Psalm 8.1)

|

The Mystical Press with Saint Augustine Andrea Mainardi (1594) Cremona, Italy Church of Saint Augustine

The above painting emphasizes the role of the Church as the intermediary between Christ and all faithful Christians: St. Gregory holds a chalice filled with the wine (Christ's blood), while other Church Fathers --St. Jerome to the right and Sts. Augustine and Ambrose to the left-- stand on either side of the winepress. St Augustine is presented prominently in the foreground pointing to Christ with his right hand.13

|

Allegory of the Sacraments (c. 1500) (German) Colmar, France Bibliothèque Municipal (Ms 306)

In the above image, the blood of Christ is shown flowing from the winepress to representations of the seven Sacraments administered by the Church, reinforcing Augustine's notion that the Church functioned as an indispensable institution leading Christians to salvation.

|

Over time, the winepress came to represent many things. Most frequently, it came to represent the cross upon which Jesus was crucified. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) maintained that because the wood of the cross "represents to us the figure of Christ extended thereon," and because it came into contact with Christ's body and was "saturated with his blood . . . in each way it is worshipped with the same adoration as Christ . . . and for this reason also we speak of the cross and pray to it, as to the crucified himself."

If, therefore, we speak of the cross itself on which Christ was crucified, it is to be venerated by us in both ways---namely, in one way in so far as it represents to us the figure of Christ extended thereon; in the other way, from its contact with the limbs of Christ, and from its being saturated with His blood. Wherefore in each way it is worshiped with the same adoration as Christ, viz. the adoration of "latria."

14 And for this reason also we speak to the cross and pray to it, as to the Crucified Himself. (Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Part III, question 25, article 40)

The French theologian Allaine of Lille (c. 1128-1202) extended the cross/winepress relationship from a focus exclusively on Christ's Passion to the suffering of all Christian martyrs (Engel 1980: 48).

The Evolution of the Winepress Motif

The concept of Christ in the Mystic Winepress is not derived from any stories concerning the life and teaching of Jesus, but rather is based on early Christian exegetical interpretations of passages from the Old and New Testaments, specifically from Isaiah and the Book of Revelation. As such, the role of Christ and the metaphor of the winepress evolved over time, reflecting changes in Christian theology, resulting in the CMW motif being employed at different times and places to represent Christ's Passion, his Resurrection, the suffering of martyrs and the Last Judgment.

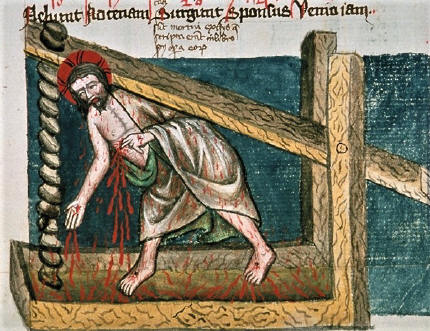

The CMW motif was most commonly presented in three distinct forms. The earliest version was that of a young Jesus standing upright treading the grapes with no press bearing down on him. This was followed by the image of Christ in the form of the Man of Sorrows, (based on Isaiah 63:3) bearing the weight of the winepress upon him, emphasizing the suffering Jesus experienced throughout his Passion and death.15 The third phase portrays a Christ Triumphant, who, at the Last Judgment, triumphs over evil (following Revelation 14:14-20, 19:11-16). Hillier (2008: 291) describes these three stages in the evolution of the winepress motif.

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, artists depicted Jesus as a serene and beardless youth trampling the grapes with none of the fury of the Isaian treader. By the fifteenth century, 'the ideas behind the typological image of the wine-treader changed and it was transformed into a eucharistic image of the Passion in the sense of a Man of Sorrows sacrificing his blood and suffering under the sins of mankind'. While Jesus treads out the vintage, sacramental blood-wine spatters his raiment. . . . Third, interpreting Revelation 19:15, where God's Word 'treadeth the winepress of the fierceness and wrath of Almighty God', Andrewes predicts that, at the Second Coming, the Son will again tread the winepress and achieve an everlasting victory.

The earliest CMW images generally do not show Jesus suffering in the winepress, but rather portray him as a serene young man treading upright in a vat of grapes, as illustrated by the two images found on the ceiling of the "small monastery" at Klein-Comburg, Germany, dated to 1108. Christ is portrayed simply treading grapes in a vat, sometimes showing the juice of the grapes flowing from the vat, affirming the connection between Jesus and the wine served during the Eucharist.

There are two CMW images in this ceiling. In the topmost image (left enlarged image below), Jesus is standing in a vat of grapes without a press. In the lower portrayal (right enlarged image below), there is a winepress, but it is not bearing down on Jesus. He is, instead, standing in the vat of grapes in front of the main beam of the winepress, with Isaiah standing to his left outside the winepress holding a banderole. These two portrayals of Jesus are typical of the earliest representations of the CMW motif. In neither image is a beam pressing down on Christ as is portrayed in later CMW representations. According to Hillier (2008: 391), in the 12th and 13th centuries "artists depicted Jesus as a serene and beardless youth trampling the grapes with none of the furor of the Isaian treader" displayed in later images.

|

|

|

After around 1400 the conceptualization of the winepress motif changed and the Christ figure in the winepress became a Man of Sorrows, sacrificing his blood and suffering to atone for the sins of mankind. The image now emphasizes Christ being trodden upon rather than being the treader, though he retains his position as treader. Hence, Pope Gregory's comment that Christ was both treader and trodder. The Christ figure is characteristically shown bent over from the weight of the beam bearing down on him, in contrast to the earlier more positive portrayals of him standing upright. To emphasize Christ's suffering during the Passion, the cross is often substituted for or added to the pressing beam, with the red stains on his clothes caused by the blood flowing directly from his wounds rather than from the fruit of the grapes.16 In addition, whereas the earliest portrayals show the Christ figure in clean clothing pressing the grapes with his feet to symbolize that the grapes which become the wine of the Eucharist represent his blood, they do not show the profuse flowing of blood from his wounds or the blood-stained clothing that dominate later portrayals.17 In different portrayals, the operator of the press varies. Sometimes it is human torturers, while other times only the winepress itself is pictured. In some cases, however, the press is operated by angels, the holy spirit or even by God the Father. The significant feature of the winepress portraying the Man of Sorrows is that Christ is a victim of the winepress, not the treader as portrayed in earlier images. He is not in control. The fact that the winepress is operated by different individuals doesn't matter, for as Schwartz (1993a: 223) points out, "Who treads is not as significant as who is being trodden."

|

Geistliche Auslegung des Lebens Jesu Christi Johann Zainer (not before 1478) Ulm, Germany (Gertzman 2013: 332, plate 19) 18

|

Anonymous (provenance unknown) |

|

Christ in the Mystic Winepress (1500) Ediger-Eller Pilgrimage Chapel

|

Mystic Winepress (1552)

Conches en Ouche |

Mystical Press

(1622)

(Engraving by Alardo de Popma)

in

Father Melchor Prieto's

Psalmodia Eucharistica

(published in Madrid)

|

Anonymous (provenance unknown)

|

Christ in the Winepress (c. 1500) Munich, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum

|

To emphasize the Eucharistic symbolism of the winepress image, the wine is frequently shown flowing into a chalice from the vat of grapes being pressed by Jesus or directly from the blood emanating from his wounds, as in portrayals of the Mass of St. Gregory and many depictions of the crucifixion (see below). The juice flowing into the chalice represents Christ's blood shed as a sacrifice for humankind at the Crucifixion. During the celebration of the Mass, for Catholics, the wine served in the chalice becomes Christ's blood through the miracle of Transubstantiation.

|

Christ in the Winepress Hieronymous Wierix Antwerp (c. 1600-1619) New York Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

Mystical Winepress (c. 1510) Ansbach, Germany Church of St. Gumbertus

|

The Mass of St. Gregory

Master of the St. Bartholomew Altarpiece

(c. 1500)

Cologne

Wallraf-Richartz Museum

The image of Jesus suffering in a winepress in which his blood flows freely from his wounds into a vat to become the wine served during the Eucharist seems quite bizarre to modern viewers, including many Christians. However, if one is to appreciate the power presented by the mystic winepress motif, it is necessary to understand the redemptive role that Christ' blood has played throughout the history of Christian worship. It is Jesus' suffering, death and resurrection that forms the core of Christian worship. The chronicle of Passion takes up nearly 40% of the overall gospel narratives. Debelius (1934: 18-24) even argues that the Passion narrative formed the core of early Christian teaching, with other parts of the gospels added later. He notes that the structure of the Passion narrative remained relatively stable throughout the four gospels, despite differences in specific details. This contrasts sharply with the considerable variation that occurred in the stories related to the life and teaching of Jesus throughout the four gospels, none of which are contained in the writings of Paul, the earliest known Christian author. For Dibelius, this suggests that the earliest Christian tradition focused almost exclusively on the death and resurrection of Jesus, with stories about his life and teaching being gradually added to the Christian corpus over time. Due to the centrality Jesus' suffering and death in Christian worship, a belief in the role that Jesus' blood plays in promoting salvation has been a central feature of Christian theology.19

Worship of the blood of Christ increased sharply during the Middle Ages. It was during this period that, according to Defoer (1980: 137), the idea of Christ "having redeemed mankind by freely taking his bloody sufferings upon himself became explicitly linked with the Eucharist in the Mystic Winepress." The blood of Christ, now identified with the consecrated wine, became "the source of all grace" (ibid.). Wardwell (1975: 21) attributes the sharp increase in the belief in the mystical powers of Christ's blood during the Middle Ages to the relics of Jesus' blood being brought to Europe by Crusaders returning from the Holy Land (see note 4). According to her (ibid.: 21-22), this produced an outpouring of literature and claims surrounding the mystical power of his blood.

This mystical approach, initially inspired by the Franciscans in the thirteenth century, was progressively intensified by the writing of mystics such as St. Heinrich Suso and St. Catherine of Sienna, who told of such remarkable mystical experiences as drinking blood from Christ's wounds. The volume of literature including plays on the subject of Christ's Passion during the fifteenth century was enormous, and every detail of pain and suffering inflicted on Christ was described as vividly as possible: how many lashes Christ received, how many thorns the crown of thorns had, how each nail was driven in, and so on and on-often to a merciless and gruesome extent. The whole point was to enable the devotee to participate as completely as possible in Christ's sufferings. The more a person identified with Christ, and the more tears he shed over the mere thought of the Passion, the more devoted he was considered to be. As a result of this mystical fervor, new devotional themes became popular such as the Man of Sorrows, the Pieta, and those like the Mystical Grapes which were directly related to the Holy Blood.

20

This belief in the mystical power of Christ's blood continues to motivate Christians today.21

One of the most moving and incisive depictions stemming from Catholic devotion to the Blood of Christ is certainly that of the "mystical winepress" . . . In these representations Christ is portrayed as the fruit squeezed, whose juice, namely His Blood, is gathered up in a vat to be the drink of redemption for the sins of man. Christ is compared with the grape and, pressed like grapes in order to obtain wine, gives vital force to mankind. As such, Christ crushed by the Cross brings forth Blood for the spiritual salvation of man. . . .

The varied iconography of the Torculus Christi demonstrates the ardent devotion of the Christian people towards the Lord's Blood, the price of our redemption, the plant of benediction, the trophy of glory, the standard of salvation. It is necessary to return to this devotion in order to focus Christianity anew on Him alone Who ransoms us at the price of His Blood which was wrenched out in the mystical winepress of the Cross. (The Feast of the Most Precious Blood)

The redemptive role of Christ's blood found expression in innumerable paintings. For example, it is through the mystical power of the blood of Christ that sinners gain salvation in Jean Bellegame's Fount of Life. In this triptych, the sinners with their impure souls, portrayed on the left, bathe in the Fountain of Life in the center containing the blood of the crucified Christ. With their souls cleansed, the former sinners enter Paradise on the right where they are welcomed by awaiting saints (see Duffy 2017: 12).

Fount of Life

Jean Bellegame

(1500-1520)

Lille

Musee des Beaux-Arts

In another composition featuring a fountain flowing with Jesus' life-giving blood, Goswijn van der Weyden shows two angels filling chalices with the blood of Christ emanating from the fountain and pouring it onto sinners below. Two of the sinners are shown praying and looking upwards towards salvation and, consequently, emerging out of the fire of Purgatory. The painting also shows Jesus and his mother kneeling on either side of the fountain pleading to God the Father above for mercy on the souls in Purgatory (Duffy 2017: 12). The title of the piece, Fons Pietitas, can be translated as "Source of Kindness".

,%20Goetenborgd%20Konstmuseum.jpg)

Fons Pietatis

Goswijn van der Weyden

(c. 1500)

(Flemish)

Goetenborg, Sweden

Goetenborgd Konstmuseum

The salvific importance of Christ's blood is also expressed in the following two images. In both compositions, a figure representing Faith, using an implement with a handle shaped like a cross, is purifying human hearts by stirring them in a vat containing blood flowing from one of Christ's wounds.

|

Faith Purifying Human Hearts with the Blood of Christ Adriaen Collaert (after Ambrosius Francken) (c. 1575-1612) London British Museum

|

La Fontaine de Vie (anonymous) 1650 (Flemish) Rouen, France Convent of the Visitation |

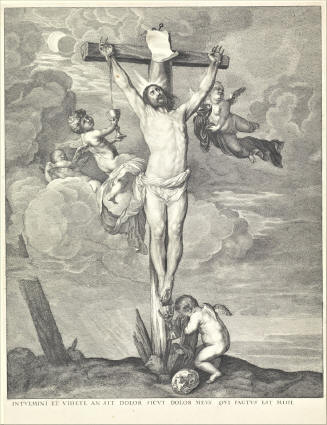

Crucifixion images from the same time period also display the worship of Jesus' blood and express the direct connection between the blood shed by Jesus and the Eucharist distributed in the form of wine during the mass. In numerous images, while on the cross, Christ directs the flow of his blood into chalices held by angels.

|

Crucifixion Attributed to Nicolo da Bologna (Single leaf from a Missal) (c. 1390) Cleveland Cleveland Museum of Art

|

Christ: Crucifixion Fiorenzo di Lorenzo (from Missal, Canon Te Igitur) (c. 1472-1499) (Perugia), New York Pierpont Morgan Library

|

|

Crucifixion Raphael22 (1502-1503) Church of San Domenico Citta di Castello Altar London National Gallery |

Crucifixion (c. 1450-1500)

(German)

Frankfurt-am-Main Staedelsches Kunstinstitut und

Staedtische Galerie

|

|

Crucifixion with Angels23 Anthony Van Dyck (c. 1632-1641) Toulouse Musee des Augustins

|

Sanguis Christi24 Francois Spierre (c. 1670) London British Museum |

.jpg)

Calvary

Master of the Death of Saint Nicholas of Munster

(c. 1470-1480)

Washington, DC

National Gallery of Art

(Below are close-ups of sections from the above image)

%20angels.jpg)

|

The Crucifixion Paolo Veneziano (c. 1340-1345) (Venice) Washington, DC National Gallery of Art |

Enlargement of Mary Magdalene caressing the bleeding wound of Christ as blood flows from the wound onto a skull by her feet. The skull, symbolizing the contemplation of death, is one of the iconographic images associated with the Magdalene in Christian art. |

The origin of the Mystical Winepress motif, in particular its association with the Eucharist, can be seen in early compositions of the Mystical Grapes, which linked the blood of Christ to the "blood" of the grape. In many of these compositions, Jesus is seen as squeezing the grapes to release their life-giving juice. Wardwell (1975) examines several Renaissance devotional tapestries that illustrate the connection between Christ's blood and the blood of grapes, a connection similarly manifested in the Mystical Winepress images. In the devotional tapestry below, the infant Christ can be seen squeezing the grape, causing its juice to flow into the cup below. At the same time, he holds a small cluster of grapes in the other hand, symbolizing himself as the fruit of the vine. An inscription along the border of the tapestry reads Porrexit manum svam in libationem et libavit de sangvinevve ["He reached his hand into the cup and poured forth the blood of the grape"] (Wardwell 1975: 17). In front of the child is a small globe with a cross on top, symbolizing Christ's crucifixion and death as redeeming of the world.

%20Metropolitan%20Museum%20of%20art.jpg)

Infant Christ Pressing the Wine of the Eucharist

(1490-1500)

(Flanders)

New York

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Wardwell examines several other tapestries that elaborate on the connection between Christ's blood and the blood of the grapes. In the following tapestry, the Christ child is flanked on his left and right by his father and mother respectively, with three angels observing the scene from behind. According to Wardwell (1975: 17-20), "the theme of redemption through Christ's incarnation and passion is reiterated in the hidden symbolism of the objects placed upon the table." For example, the crossed globe held by the child's left hand signifies "the universal supremacy of his redemption". The apple placed on top of a cup is the symbol for sin and death resulting from Eve's temptation, which his resurrection conquers. The central importance of the child squeezing the grapes, according to Wardwell, is demonstrated by the fact that only the Christ child is looking straight out; everyone else in the scene is concentrated on him and his squeezing of the grapes. "The occasion is the celebration of the Eucharist, the shedding of Christ's blood for the redemption of mankind." (Wardwell 1975: 17).

Mystical Grapes

(c. 1500)

(Flanders)

Cleveland

Cleveland Museum of Art

Images portraying Christ squeezing grapes, which represent the Eucharistic wine, were quite common and continue to be used as part of Christian worship.

|

Eucharistic Christ

17th century

Historical Museum in Sanok

In the above painting, Jesus, wearing a crown of thorns, squeezes the

grapes representing his blood into the chalice symbolizing the Eucharist.

The grapevine from which the grapes are produced grows out of the wound on

his side caused by the spear that was thrust into his body while on the

cross. In the background of the painting is the pole to which Jesus was tied

and whipped during his scourging. |

Jesus Christ in the Mystical Press (18th century) Lublin, Poland National Museum in Lublin In the above painting, Jesus also squeezes the grapes representing his blood into the chalice symbolizing the Eucharist. Similarly, the vine from which the grapes are produced grows out of the wound on his side. However, in this painting Jesus is shown without the crown of thorns or the pole he was tied to during his scourging, but he is accompanied by an angel holding the chalice. |

|

Allegory of the Holy Sacrament Juan Correa (Mexico) (c. 1690) Denver Denver Art Museum (Credidimus Caritati: Precious Blood of Jesus)

In the above painting, Christ is also shown squeezing grapes while wearing a crown of thorns, and, as with other similar paintings, the grapes are shown growing on a vine originating in the wound on his side. In this case, however, the juice of the grapes (representing his blood transformed into the Eucharistic wine) is being squeezed onto a platter held by the Pope, who represents the authority of the Church over the distribution of the Eucharist. The banner above Jesus reads "PATER INOSCE ILLIS", ("Father forgive them"), words believed by Christians to have been spoken by Jesus on the cross (Luke 23:34). a flock of sheep symbolizing the faithful congregate around a baptismal font and look up in adoration. Kneeling on a blue orb, a symbol of the universality of the Church’s power, Christ holds in his hands grapes on a vine that grow out of the wound on his chest. As Christ squeezes the grapes, his own blood falls onto a silver liturgical platter held by the pope. Directly behind stands a wooden crucifix, a symbol of Christ’s death on the cross. (see Allegory of the Holy Sacrament, Denver Art Museum) |

Mystical Winepress (1890) Brasov District , RomaniaZosim Oancea Museum of Icons on Glass,

The above reverse painting on glass is unique to Romanian folk art. In this painting, the grapes are typically shown growing on a vine originating in the wound on Christ's side. Similar to two of the other paintings shown here, Christ is squeezing the grapes borne from his wound into a chalice, which represents the Eucharist.

The Zosim Oancea Museum of Icons on Glass, located in the Carpathian Mountains in the Transylvania region of central Romania, possesses a unique collection of icons painted on glass. According to the Museum web page, painting on glass was an ancient art form introduced into Transylvania following its annexation into the Habsburg empire in 1699. The style of the above painting is representative of icons produced in the Braşov District of Romania. |

The notion that Christ is the fruit of the vine and that his blood becomes the blood of the grape is further symbolized by images of the

Madonna of the Grapevine, in which the virgin is viewed as the vine that produced the grape, which is Christ. This was symbolized in paintings and in sculptures by having the Madonna hold the Christ child in one hand and a bunch of grapes in the other.25

|

The Virgin and Child with a Bunch of Grapes 26Lucas Cranach the Elder (c. 1509-1510) (German) Madrid Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

|

The Holy Family The Master of St. Sang (c.1520) Hamburg Kumsthalle Museum (Wardwell 1975: 20) |

Rest on the Flight into Egypt

Jan Massys

(c. 1537-1540)

New York

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Protestant Reformation and Catholic Counter-Reformation

As mentioned earlier, the image of Christ in the Mystic Winepress was one of the few Catholic concepts that survived the Protestant Reformation. However, the interpretation and presentation of that image changed dramatically. While Catholic theologians emphasized the winepress as symbolizing Christ's Passion, Protestant theologians placed greater emphasis on the winepress as representing Christ's triumph over evil.

27 Rather than portraying Jesus as the Man of Sorrows suffering for the sins of mankind or shedding blood that becomes the Eucharistic wine, the Christ in the winepress became a triumphant figure who would conquer sin and evil in the world. Martin Luther called the winepress-Passion link “absurd”28 and promoted Revelation 19:15 as a the manifestation of Isaiah 63:2 (Engel 1980: 49). Calvin also denied that the person represented in Isaiah was Christ suffering. He interpreted the Isaiah passage as a reference to the Last Judgment in which a triumphant Christ exacts his vengeance on God’s enemies, as represented by the triumphant Christ portrayed on the cover of the Lutheran Bible.|

Title Copper of Ernestine Bible (1649)

|

Elector (Nuremberg) Bible

Title Page

(1649-1758

|

The Ernestine and Elector Bibles were two of the various names given to the Martin Luther translation of the Old and New Testaments into German. Luther’s translation was authorized by the Duke of Saxe-Gotha and printed by Wolfgang Endters in Nuremberg, Germany from 1641-1758. The title copper of the Ernestine bible was made for the Holzepitaph of Conrad Lemmers and his wife in 1649. The CMW image in the title page of the Elector Bible places a triumphal Christ in a winepress atop Golgotha, the site of his crucifixion.

Joseph Hall, Anglican Bishop of the Diocese of Norwich (1641-1656), also interpreted Isaiah as a reference to the Final Judgment rather than to Christ's Passion. In his commentary on Isaiah 13:3, Hall (1837: 406), has Christ reply to the question of whether his garments are bloody because of the Passion or the Judgment.

It is true, O my Church, I have been indeed treading the winepress of my Father's wrath: I have been crushing and trampling upon all the clusters of mine enemies; even I alone, by my mighty power, have trod them under my feet, without the supply of all other helps: the victory is mine alone, which I will in my good time, fully accomplish; for I will in my just anger, be exquisitely avenged of all those, that maliciously rise up against me, and will give proofs to the world of my vengeance and their sufferings.

Hall's use of the triumphal winepress motif can also be seen when he likens Christ's defeat of his enemies to Samson's victory over the Philistines.

It is no marvel if he were thus admirably strong and victorious whose bodily strength God meant to make a type of the spiritual power of Christ : and behold, as the three thousands of Judah stood still gazing with their weapons in their hands, while Samson alone subdued the Philistines; so did men and angels stand looking upon the glorious achievements of the Son of God, who might justly say, I have trod the winepress alone. (Winter 1863: 275)

The Mystic Winepress became another means by which Protestant reformers expressed their opposition to Catholicism. Isaiah (63:3-5) emphasizes not only the winepress as representing Christ’s triumph and punishment of evil, but also of Christ accomplishing his victory alone in much the same way that Christians, according to Reformation teaching, had to achieve their own salvation, i.e., free from the control of the Catholic Church hierarchy and its self-serving rituals and rules. Moreover, in line with Protestant teaching that redemption was to be achieved through faith in Christ alone, not through performing the rituals and sacraments authorized by the Catholic Church, Protestant interpretations of the Mystic Winepress were frequently targeted directly at the Catholic Church. Calvin, for example, in a chapter titled De sacrificio missae written in 1549, argued that the sacrifice of Christ on the cross was a unique act and was, thus, inappropriate to be repeated with each celebration of the mass (Llobet and Famadas 2019: 42), a direct challenge to Catholic teaching. Rejecting the Roman Catholic belief in Transubstantiation, Protestant use of the winepress motif often took the form of an attack on the sacrament of the Eucharist. This hostility towards the Catholic Church is expressed in Georg Pencz’ engraving included to illustrate Hans Sachs', The Seven Obstacles on the Christian’s Way to Salvation (see image below). This was an older image, adapted by Protestant reformers to promote both their new theology and opposition to Roman Catholic teaching. Llobet and Famadas (2019: 46) provide a description of the engraving, its theological interpretation, and its expression of Protestant reformers' opposition to the Catholic Church.

In their search for salvation, the pilgrims follow the road from the Old Law, represented by Moses on Mount Sinai on the left side of the engraving, to the Resurrection on the right. After undergoing a number of trials such as the attack by Catholics in the form of wild beasts, one of them points out the road they should follow, which is the blood of Christ flowing out of, the winepress, and there they rid themselves of their sins before arriving at Mount Zion, where they surround the resurrected Christ, with the Lamb of God depicted at the top of the scene. The text makes it meaning and function even clearer as an image of redemption: the sinners find salvation thanks to their search for faith and truth in Christ, and there are no intermediaries between man and Christ. In this case, satire is combined with the teaching of the doctrine itself and, as in some Reform works, the Catholics are ridiculed.

[cropped].jpg)

The Seven Obstacles on the Christian Way to Salvation

Georg Pencz

(Nuremberg)

1529

London

British Museum29

(#E,8.164)

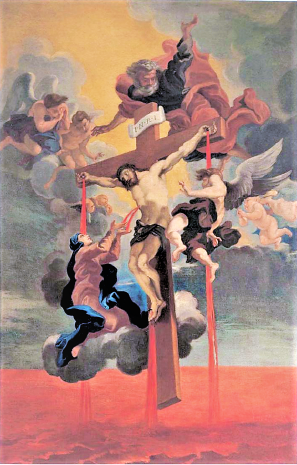

The Catholic Church’s response to Protestant criticisms was to defend its position as the sole authority of Christian teaching and its indispensable role as a guide to salvation. Defoer (1980: 137) indicates that CMW representations emphasizing the part played by the Church as Christ's representative on earth first appeared at the end of the 15th century and occur mostly during the 16th and 17th centuries, mainly in northern France. He suggests that these were part of the Church's reaction to the Reformation, whose proponents denied both the miracle of the transubstantiation (and, thus, Catholic teaching regarding the Eucharist) and the authority of the Church as the sole dispenser of Christ's grace. Popes and saints, for example, are shown filling jars with the wine produced by Christ's blood in Marco Pino's Christ in Glory above the Mystic Winepress.

.jpg)

Christ in Glory above the Mystic Winepress

(lower portion)

Marco Pino

(c. 1571)

Vatican Pinacoteca

Similarly, in Peter Aertsen's, The Mass of St. Gregory with the Mystic Winepress (below), Christ is pictured leaning forward under the pressure imposed by the cross/winepress placing one foot on the altar with his blood flowing into a chalice held high by Pope Gregory, assisted by two deacons, affirming that the wine consecrated during the mass is identical to Christ's blood. In addition, in the left background of the painting St. Peter, claimed by the Roman Catholic Church as the first pope,30 can be seen treading the grapes cast into the vat by the other apostles. Peter's attribute portrayed in this painting is not the "keys of the kingdom of heaven" given to him by Jesus (Matthew 16:19), but the upside-down cross upon which the late second century apocryphal Acts of Peter (3.37-38) claims he was crucified. To the left of the altar, saints and martyrs, including St. Agnes and St. Lawrence (identified by their attributes) are pouring pitchers of wine into a wine barrel marked with the veil of St. Veronica and Jesus' five wounds. These saints are assisted by two bishops (Probably St. Augustine and St. Ambrose), while Sts. Jerome and Gregory are capturing in pitchers the wine spurting out the left side of the Mystic Winepress. In the background on the right, a barrel of wine is being transported on a cart accompanied by the symbols of the Four Evangelists. The cart is being drawn by St. Paul and delivered to the pope and emperor, embodiments of ecclesiastical and secular authority. Closer to the front of the drawing, a barrel is being stored by a king and high church dignitaries in a wine cellar, i.e. the Church. (Description taken from Defoer 1980: 137-138.) Defoer (1980: 139) provides an interpretation of Aertsen's Mass of St. Gregory.

The meaning of Aertsen's composition can be summed up as follows: Christ, through the sacrificial death he freely took upon himself, has redeemed man kind. His death had been foreseen from the beginning by God, who had already planted and tended his vineyard in the Old Testament. Christ's work is continued by the Apostles and saints, while the fruits of his redeeming death are spread throughout the world by the Gospel. The stewardship of the wine is entrusted to the Church, which is supported in its task by the secular authorities. The fruits of Christ's sufferings are made available primarily via the Eucharist, in which Christ himself is corporeally present.

|

The Mass of St. Gregory with the Mystic Winepress

Pieter Aertsen (c. 1550s)

Utrecht St. Catherine's Convent Museum

|

Numerous variations on the theme of The Mass of St. Gregory have been painted (see Defoer 1980; Pierce 2004) based on legends claiming that Pope Gregory witnessed the presence of Christ on the altar at the very moment he elevated the host during its Consecration in the mass (Pierce 2004: 97).31 These legends spread following the Fourth Lateran Council (1213), which declared transubstantiation (the physical transformation of the bread and wine offered in the sacrament of the Eucharist into the actual body and blood of Christ)32 as official Church dogma, and were promoted as proof of the dogma's veracity. Owing to the popularity of these legends, devotion to the mass of St. Gregory spread and became firmly established throughout Europe.33

A similar emphasis on the role of the Church as the authoritative representation of Christ can be seen in Jacques Laouette's, Le Pressoir Mystique (shown below). This illustration, like The Mass of St. Gregory above and several other CMW representations (including the stained-glass window in the Saint Etienne-du-Mont Church in Paris presented earlier and likely based on Laouette's illustration), shows Christ in a winepress with his blood flowing into a receptacle, from which it is collected, placed in barrels and stored in a wine cellar (the Church) by ecclesiastical and secular authorities. St. Peter is similarly shown treading grapes in a vat, and barrels of Christ's blood are likewise shown being transported in a cart containing the representations of the Four Evangelists (see Defoer 1980: 138-139).34

Le Pressoir Mystique

(The Press of Our Savior Jesus Christ)

Jacques Laouette

(c. 1572-1595)

Paris

Bibliothèque Nationale

The CMW Motif in Sermons, Hymns, Literature and Music35

The use of the Mystic Winepress image was common in hymns and sermons of the late medieval period. As with the visual representations, most non-visual references to the winepress occurred in northern Europe. Ironically, the winepress metaphor was frequently applied in English compositions, despite the complete absence of CMW images throughout Great Britain.

Lancelot Andrewes (1555-1626), Bishop of Chichester, used the winepress motif frequently when commenting on the suffering experienced by Jesus on the cross:

This was the pain of "the press", so the Prophet [Isaiah] calleth it, torcular ["winepress"], wherewith as if He had been in the wine-press, all His garments were stained and gored with blood.' (quoted in Hillier 2008: 391),

Andrewes based his 1623 Easter Sermon on Isaiah 63:1-3. In that sermon, Andrewes mentions the winepress 24 times (see Dorman 2002, passim). Hillier (2008: 391) notes Andrewes' identification of three winepresses that were manifested throughout Christian history:

(1) Christ's Agony in Gethsemane;36

Christ's 'unnatural' bloody sweat (Luke 22:44) was 'as if He had been wrung and crushed in a winepress'. (Dorman 2003, sermon 3; quoted in Hillier 2008: 391)

(2) In the Passion of Christ;

[Christ] became Calcator ["the Treader"]. He who was thrown Himself, threw them now another while into the press, trod them down, trampled upon them as upon grapes in a fat, till He made the blood spring out of them, and all to sprinkle His garments, as if He had come forth of a winepress indeed. And we before, mercifully rather than mightily by His Passion, now mightily [are] also saved by His glorious resurrection. (Dormian 1993: 186; quoted in Hillier 2008: 391)

(3) Quoting Revelation 19:15, "where God's Word '

treadeth the winepress of the fierceness and wrath of Almighty God',

"Andrewes predicts that, at the Second Coming, the Son will again tread the winepress and achieve an everlasting victory." (Dorman 1993: 187; quoted in Hillier 2008: 391)

Hillier adds that in his Paschal Sermon that same year, Andrewes states,

Twice [Christ] was a winepress. On Good Friday when He was, like the grapes, trodden on and pressed, the other as on Easter day when He was the winepress and trampled upon sin, and drank the fruits of the winepressing for us. (Domian 1993: 184, quoted in Hillier 2008: 405, note 52)

Hillier (ibid.) also discusses a Lenten sermon given by John Donne in 1620 in which Donne imagines a dialogue between Christ and his angels in which he introduces the winepress metaphor.

There [angels] say with amazement, Quis iste? Who is this that cometh from Edom, with dyed garments from Bozrah? And Christ answers there, Ego, it is I, I that speak in righteousness, I that am mighty to save. The Angels reply, Wherefore are thy garments red, like him that treadeth the wine-press? and Christ gives them satisfaction, calcavi; You mistake not the matter, I have trodden the wine-press; and calcavi solus, I have trodden the winepress alone, and of the people there was none with me. The Angels then knew not this, not all this, not all the particulars of this; The mystery of Christs Incarnation for the Redemption of Man, the Angels knew in generall. (Potter and Simpson 1953-1962: 217, quoted in Hillier 2008: 391)

Engel (1980: 54) notes that whenever Donne spoke at length in his sermons on sin's spiritual burden, he repeatedly used words like "press", "suppress" and "oppress'.

According to Engel (ibid: 45), the Jesuit priest, Robert Southwell (1561-1595), similarly viewed the Passion of Christ through the winepress image in his poem "Christ's Bloody Sweat,"

Fat soile, full spring, sweete olive, grape of blisse,

That yeelds. that streams, that pours, that dost distil,

Untild, undrawne. unstampt, untoucht of presse,

Deare fruit, cleare brookes. faire oile, sweete wine at will

Thus Christ unforst prevents in shedding blood

The whips, the thornes. the nailes. the speare, and roode

(McDonald and Brown 1967:18-19; quoted in Engel 1980: 45-46)

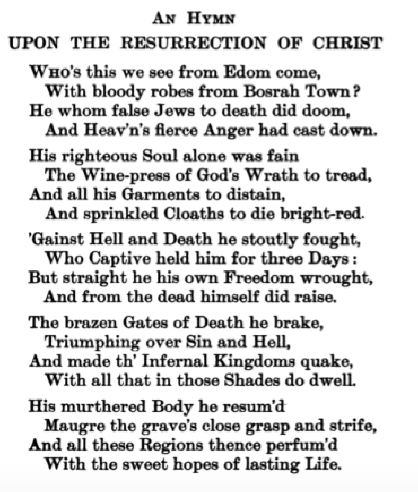

Henry More (1614-1687), a prolific theologian and philosopher at Christ's College Cambridge, included a hymn with a reference to the "Wine-press of God's Wrath" among his many writings (see Ward 1710: 262).

Engel (1980) states that several 17th century poets also employed the CMW image.

Seventeenth-century English poets, like their Continental counterparts, were fascinated with the motif of Christ in the Winepress. A quick glance through some of the major poets of this time period underscores not only the popularity of this image but also the impressive -and sometimes confusing- variety of meanings and associations attached to the winepress. (Engel 1980: 45)

According to Engel, the winepress image lies at the heart of George Herbert's poem, "The Agonie", where the second stanza reads,

Who would know Sinne, let him repair Unto Mount Olivet; there shall he see

A Man so wrung with pains, that all his hair, His skinne, his garments bloudie be.

Sinne is that presse and vice, which forceth pain To hunt his cruell food through ev'ry vein.

(Hutchinson 1941: 37; quoted in Engel 1980: 45)

and the poem concludes,

Love is that liquor sweet and most divine,

Which my God feels as blood: but I taste as wine.

Engel also maintains that Christ's suffering and death on the cross provided Henry Vaughan with a context for exploring the winepress image in his poem, "The Passion":

Most blessed Vine!

Whose juice so good

I feel as Wine,

But thy faire branches felt as bloud,

How wert thou prest

To be my feast!

In what deep anguish

Didst thou languish,

What springs of Sweat and bloud did drown thee!

How in one path

Did the full wrath

Of thy great Father

Crowd, and gather,

Doubling thy griefs, when none would own thee!

(Fogle 1969: 184-186; quoted in Engel 1980: 46)

Engel contrasts Herbert's application of the winepress metaphor to Christ's suffering with its use by Milton (at the opening of Book IV) in Paradise Regained as a symbol of Christ's triumph over Satan.

The strength he was to cope with, or his own:

But as a man who had been matchless held

In cunning, over-reacht where least he thought,

To salve his credit, and for very spite

Still will be tempting him who foils him still,

And never cease, though to his shame the more;

Or as a swarm of flies in vintage time,

About the wine-press where sweet moust is powrd,

Beat off, returns as oft with humming sound;

Or surging waves against a solid rock,

Though all to shivers dasht, the assault renew,

Vain battry, and in froth or bubbles end;

So Satan, whom repulse upon repulse

Met ever; and to shameful silence brought,

Yet gives not ore though desperat of success,

And his vain importunity persues.

(Darbishire 1958: 323; quoted in Engel 1980: 56-57)

Engel (ibid.: 62, note 47) mentions other 17th century poets who employed the winepress image in relation to Jesus' suffering on the cross, including Henry Mores (1613-1687) in his poem, "An Hymn upon the Resurrection of Christ" [His righteous Soul alone was fain / The Wine-press of God's wrath to tread], and Francis Quarles in his Divine Fancies (1630) [Me thinkes, the grapes that cluster from that Vine. / Should (being prest) afford more blood then wine]. Engels (ibid.: 54) calls Phineas Fletcher's The Purple Island (1633) "perhaps the longest elaboration of the winepress image in English or any other language." He also mentions, but does not quote, two later poets who, he believes, made interesting use of the winepress motif in their writing: the puritan preacher Edward Taylor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony (1642-1729), and Father Gerhard Manley Hopkins, S.J. (1884-1889) in his poem, "Barnfloor and Winepress." Examples of the use of the winepress image by either Fletcher or Taylor could not be found; however, that by Hopkins could.

|

"Barnfloor and Winepress"

"If the Lord do not help thee, whence shall I help thee? out of the barn-floor, or out of the wine-press?" (2 Kings 6:27)

THOU who on Sin’s wages starvest, Behold we have the Joy of Harvest: For us was gathered the First-fruits, For us was lifted from the roots, Sheaved in cruel bands, bruised sore, Scourged upon the threshing-floor, Where the upper millstone roofed His Head, At morn we found the Heavenly Bread; And on a thousand altars laid, Christ our Sacrifice is made. Thou, whose dry plot for moisture gapes, We shout with them that tread the grapes; For us the Vine was fenced with thorn, Five ways the precious branches torn. Terrible fruit was on the tree In the acre of Gethsemane: For us by Calvary’s distress The Wine was rackèd from the press; Now, in our altar-vessels stored, Lo, the sweet Vintage of the Lord! (verses 1-20; Miles 1894) |

Father Gerard Manley Hopkins, S. J.

(1844-1889)

|

Although religious applications of the CMW motif declined significantly following the 17th century, a few later references can be found. Braatz (2005) draws a comparison between Isaiah 53:5 and a line included in Heinrich Müller's 1737 poem, Himmlischer Liebeskuß ("Heavenly Love Kiss")

But he was wounded and crushed for our sins. He was beaten that we might have peace. He was whipped, and we were healed! (Isaiah 53:5)

Die Angst hat ihn so gekältert, daß sein ganzes Leichnam wie eine zerdrückte Kirsche Blut gespritzet. Da hat der heilige Leib Christi müssen zerknirschet werden, und wie eine Weintraube zerfliessen. (Heinrich Müller ["Liebeskuß," Hof, 1737, p. 50; quoted in Braatz 2005)

("Fear chilled him so much that his whole body spurted blood like a crushed cherry. There the holy body of Christ must be contrite and melt like a bunch of grapes.")