THE BIRTH OF JESUS

The Evolution of Jesus in the Infancy Narratives

William S. Abruzzi

(2020)

And

it came to pass in those days that a decree went out from Caesar Augustus

that all the world should be registered. This census first took place while

Quirinius was governing Syria. So all went to be registered, everyone to his

own city. Joseph also went up from Galilee, out of the city of Nazareth,

into Judea, to the city of David, which is called Bethlehem, because he was

of the house and lineage of David, to be registered with Mary, his betrothed

wife, who was with child. So it was, that while they were there, the days

were completed for her to be delivered. And she brought forth her firstborn

Son, and wrapped Him in swaddling cloths, and laid Him in a manger, because

there was no room for them in the inn. (Luke 2:1-7)

Every

year at Christmastime, millions of Christians throughout the world hear these

words from Luke's gospel. They also hear stories of three Wise Men traveling

from the East to pay homage to the newborn "King of the Jews;" of shepherds

"tending their flocks in the field;" of a star shining over the place of Jesus'

birth in Bethlehem; of visits by angels; of warnings given in dreams; of the

massacre of innocent children by the evil King Herod in his attempt

to kill the infant Jesus; and of Joseph, Jesus' earthly father, taking his

family to Egypt in order to escape Herod's wrath. While these tales provide a beautiful prelude to opening gifts under the Christmas tree, none of them is

true. They are all fables. Indeed, the modern version of the Christmas tale is a

synthesis of several independent stories merged into two distinct and contradictory infancy narratives presented in the opening chapters of the

Gospels of Matthew and Luke. Most Christians are completely unaware of the

inherent contradictions presented by the two infancy narratives. In fact, Bart

Ehrman

maintains that most Christians believe in what he calls a "Fifth Gospel," a

synthesis of the four canonical gospels that merges the distinct stories presented in each

gospel into a single narrative of the life and teaching

of Jesus. Most Christians, according to Ehrman, do not know the four gospels as

such; rather, they are aware only of the broad outline of Jesus' life and

mission and are oblivious to the

fundamental differences and contradictions that exist among the gospels and of the distinct

portrait of Jesus each gospel presents. Christian beliefs regarding the birth of Jesus

suffer from the same limitations as Christian understanding of the gospels

generally.

In

the essay that follows, I examine various stories surrounding the birth of Jesus

in the light of current biblical scholarship. Two broad categories of research methods inform modern

biblical research: Biblical Exegesis

(the critical examination of biblical texts), and the

Critical Historical Method

(an examination of biblical stories in the light of historical and social

science research). Modern biblical scholarship follows the same methods

applied to the analysis of any historical text.

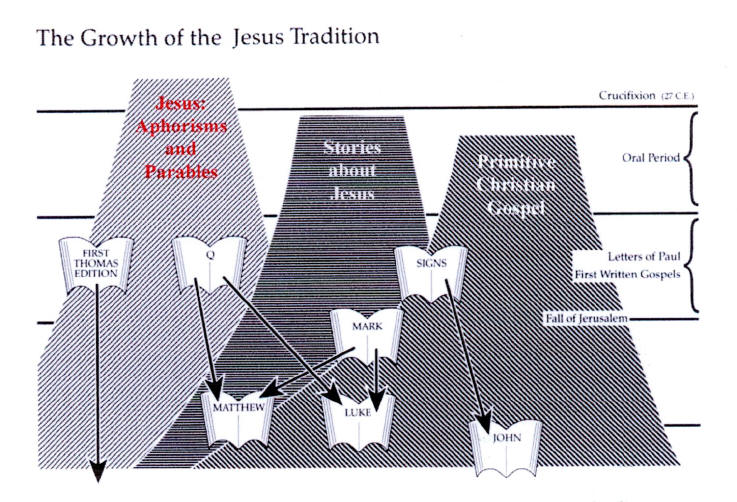

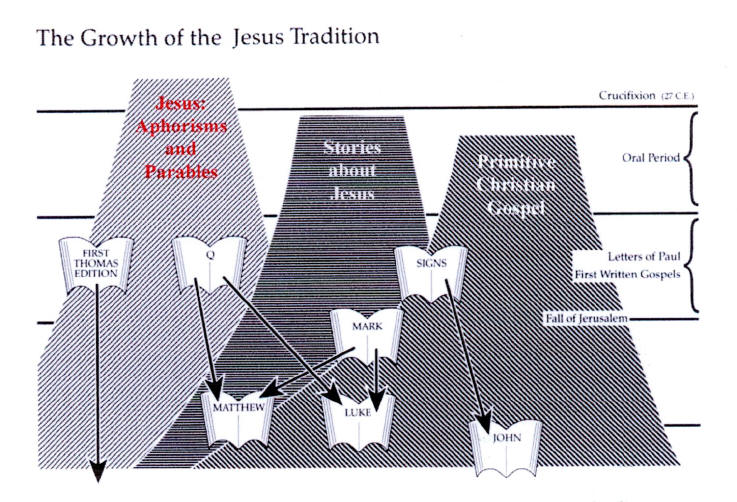

The Gospels

To understand the birth stories of

Jesus, we need to understand the gospels in which they are included; and to

understand the gospels, we need to examine the authors who wrote them, as well as

the audiences to whom they were directed. Without going into a detailed

discussion of the theologies and other characteristics that are known about the

purported authors (Mark, Matthew, Luke and John), one thing is clear: they

were not eyewitnesses to the events they describe. Current biblical scholarship

dates the gospel attributed to Mark (generally accepted as the earliest of the canonical

gospels) to around 70 CE (Common Era, formerly A.D.). The gospels attributed to

Matthew and Luke are generally dated between 80-90 CE, while the gospel

attributed to John is thought to have been written between 90-100 CE. Clearly,

given these dates, it is highly improbable that any of the gospel writers were

themselves eyewitnesses to specific events in Jesus' life. They most

certainly were not present at Jesus' birth. Nor were they present at the Sanhedrin

meetings where plans were made to arrest Jesus, at Jesus' trial before the

Sanhedrin or his trial by Roman authorities, none of which would have been public affairs. They were also not present to

take notes when Jesus was telling the various parables contained in the first

three gospels or making the long speeches presented in the fourth gospel.1

The gospels were based on stories handed down for some 2-3 generations and contain all the

problems of accuracy and validity associated with such stories. (For a good

example of how quickly stories can become distorted and mythologized, even in a

literate and educated society, see Abruzzi

The

Myth of Chief Seattle.)

In a court of law, most of what

is contained in the gospels would be classified as "hearsay."

Evidence also exists which clearly suggests that the authors of the four gospels were

not native to Palestine. Mark's

description of the land descending into the Sea of Galilee and his story of

Jesus walking 70 rather than 40 miles from Tyre to the Sea of Galilee following

a route through Sidon the region of the Decapolis (Mark 7:31) demonstrate an

ignorance of Palestinian geography. Similarly, Mark (10:11-13) displays

ignorance of Jewish customs when he has Jesus telling a parable involving a woman

who divorces her husband, a behavior that would have been impossible among the

Jews of Palestine at that time. Luke (1:59-61) also demonstrates an ignorance of

Jewish customs when he claims that the baby John the Baptist was to be named

Zechariah after his father until Elizabeth, his mother, obeying the instructions

of the angel, objected, saying, "No, he is to be called John." This deviation

from tradition, according to Luke, generated critical comments among their

neighbors. However, Jews did not traditionally name a son after the father. In

fact, according to Asimov (1969: 922), there is not a single case in the Old Testament of a son being named for a

living father, and "is still not done by pious Jews today." Similarly, Luke (2:22) claims that

Joseph and Mary brought Jesus to the temple following his birth because

"the time came for their purification."

However. the law in Leviticus

(12:1-5) requires only the mother to be purified after giving birth, not the

father.

Purification of Women after Childbirth

The Lord said to Moses,

"Say to the people of

Israel, If a woman conceives, and bears a male child, then she shall be unclean

seven days; as at the time of her menstruation, she shall be unclean. And on the

eighth day the flesh of his foreskin shall be circumcised. Then she shall

continue for thirty-three days in the blood of her purifying; she shall not

touch any hallowed thing, nor come into the sanctuary, until the days of her

purifying are completed.

But if she bears a female

child, then she shall be unclean two weeks, as in her menstruation; and she

shall continue in the blood of her purifying for sixty-six days.

Several researchers (cf. Dibelius 1956;

Goulder 1957; Oliver 1964; Minear 1966; Haenchen 1966; Brown 1977; Fitzmyer

1981; Goulder 1989; Freed 2001) have provided ample evidence that illustrates Luke's unreliability as a historian.

In a statement that would be seconded by many scholars, Haenchen (1966:260) concludes that

the evangelist "is not so much

a historian in our sense of the word as he is a fascinating narrator." (see Abruzzi

When Was Jesus Born?)

Finally, the gospels lack the elements usually found in eyewitness

accounts. They rarely include the kind of details and information one would

expect from first-hand descriptions of events. None of the gospel writers, for

example, includes themselves in any of the events that took place, as would be

expected had they actually witnessed the events they describe.

Furthermore, Luke (1:1-3) begins his gospel with the following words,

Inasmuch as many have

undertaken to compile a narrative of the things which have been accomplished

among us, just as they were delivered to us by those who from the beginning were

eyewitnesses and ministers of the word, it seemed good to me also, having

followed all things closely for some time past, to write an orderly account for

you, most excellent Theoph'ilus.

2

Luke's introduction indicates rather clearly that he was

not an eyewitness and, in fact, based his account on others who were the

original "eyewitnesses and ministers of the word."

Along

the same lines, if Matthew and Luke were eyewitnesses to the events they

describe, Matthew would not have depended on Mark for nearly two-thirds of his

stories; nor would Luke have depended on Mark for nearly half of his stories.

Indeed, except for about 40 verses, the whole of Mark's gospel is

reproduced nearly word-for-word in Matthew. If Matthew had actually witnessed

the events he described, he clearly would have had his own stories to tell, and

he would have told them in his own words.

Who

are the authors of the four canonical gospels? While Christians have universally

accepted that individuals named Matthew, Mark, Luke and John composed the four

gospels, and while these four individuals have all been canonized as Christian saints, the reality is that no one knows

who wrote the four canonical gospels, or if they were even written by specific

individuals. Authorship of these gospels was not attributed to the four

currently named individuals until 175 CE by Irenaeus, the bishop of Lyon (Ehrman

1997:79). There was, in fact, intense disagreement regarding which gospels

should be considered canonical throughout the first four centuries of the

Christian era. While there were dozens of Christian gospels in existence (see

Hedrick 2002), including such well-known Gnostic gospels as the

Gospel of Thomas, the

Gospel of Philip, and the

Gospel of Mary (see

Pagels 1979) and the Gospel of the Hebrews,

the Gospel of the Nazaraeans

and the Gospel of the Ebionites,

generally attributed to early Jewish Christians in Palestine (see Munck 1960),

Irenaeus was insistent that there were only four legitimate gospels, the current

four canonical gospels, which he named. Irenaeus' reasoning for the existence of

only four canonical gospels would hardly survive scrutiny today.

The

Gospels could not possibly be either more or less in number than they are. Since

there are four zones of the world in which we live, and four principal winds,

while the Church is spread over all the earth, and the pillar and foundation of

the Church is the gospel, and the Spirit of life, it fittingly has four pillars,

everywhere breathing out incorruption and revivifying men. From this it is clear

that the Word, the artificer of all things, being manifested to men gave us the

gospel, fourfold in form but held together by one Spirit. As David said, when

asking for his coming, 'O sitter upon the cherubim, show yourself '. For the

cherubim have four faces, and their faces are images of the activity of the Son

of God. For the first living creature, it says, was like a lion, signifying his

active and princely and royal character; the second was like an ox, showing his

sacrificial and priestly order; the third had the face of a man, indicating very

clearly his coming in human guise; and the fourth was like a flying eagle,

making plain the giving of the Spirit who broods over the Church. Now the

Gospels, in which Christ is enthroned, are like these.

(Against

Heresies

3.11.8)

(quoted in Stanton 1989: 134)

The Synoptic Gospels

As already indicated, the general consensus among biblical scholars is that

Mark is the earliest of the gospels. In addition, Mark, Matthew and Luke are

classified together as the

Synoptic Gospels

(synoptic = "to see with one eye")

owing to the similarity of their stories about Jesus, which is to be expected

given that the stories in Matthew and Luke largely derived from those in Mark.

Indeed, fully 80% of Mark's gospel is reproduced by Matthew, while about 65% is

reproduced by Luke (Ehrman 1997). In addition, Matthew and Luke agree in

sequence "only to the degree that they both agree with Mark" (Fitzmyer 1970:

136). Luke rarely changed the order of Mark's stories, while Matthew changed it

only 7 times (Stanton 1989: 35). Only once (Luke 22:59) does Luke include a

chronological reference that is not already present in Mark (Stanton 1989:84).

In addition, "Matthew and Luke never agree with one another against Mark in

regard to the order of episodes" (Fitzmyer 1970: 136). Matthew and Luke,

however, routinely modified and added to (i.e.,

redacted) Mark's account in

order to adapt Mark's stories to fit their own theologies. In Matthew, many of

Mark's stories were modified to accommodate Old Testament prophecies that

Matthew wanted to attribute to Jesus. Luke, on the other hand, frequently

altered Mark's account in order to make Jesus more sympathetic and amenable to

Gentiles (non-Jews).

While some might want to

argue that Mark borrowed from Matthew and Luke, or that Mark, Matthew and Luke

all borrowed from each other or from another earlier source, Fitzmyer (1970: 134-147)

details the reasons why scholars nearly universally accept the

priority of Mark among the Synoptic Gospels. The priority of Mark clearly

emerges when examining individual texts contained in the three gospels. One

obvious question, for example, is why would Mark (the shortest of the gospels)

have abbreviated and conflated the more elaborate versions of the same stories

contained in Matthew and Luke. Indeed, the normal direction of the subsequent

retelling of stories is an increase --not a decrease-- in the elaboration of

story details (see Funk, Hoover et. al. 1993: Chapter 1). Why also would

Mark have omitted such important and popular stories as the Sermon on the Mount from Matthew

and the Good Samaritan in Luke? Similarly, why would Mark have eliminated all

traces of both Matthew's and Luke's infancy narratives? Given Mathew's and

Luke's more elaborate resurrection narratives, Mark's almost non-existent

resurrection narrative makes no sense, if Mark borrowed from them rather than

they from him. Throughout the gospel, the Christology presented by Mark is

substantially less developed than that presented in the other gospels, and

reflects an earlier and theologically less developed conceptualization of Jesus and his mission.

Thus, "given Mark, it is easy to see why Matthew and Luke were written; but

given Matthew and Luke, it is hard to see why Mark was needed in the early

Church." (Fitzmyer 1970: 135).

It is also difficult to

explain why, having Matthew's gospel in hand, Luke should only follow Matthew's

order when it agrees with Mark. If Luke borrowed equally from Matthew and Mark,

or if Matthew borrowed equally from Luke and Mark, or if all the three

evangelists borrowed equally from an earlier source, there should be numerous

agreements in order between Matthew and Luke against Mark; but "there are next

to none." (Fitzmyer 1970: 138). Bart Ehrman (1997:

Chapters 5-10) presents a detailed analysis of the four canonical gospels,

which similarly demonstrates the primacy of Mark among the Synoptic Gospels and

which illustrates the manner in which Matthew and Luke both redacted Mark's

material to accommodate their own theologies. Given such extensive

interdependency among the various gospels, they cannot be considered multiple

and independent affirmations of Christian beliefs about Jesus. The fact that a

particular story exists in more than one gospel may simply indicate that one or

more later writers borrowed the story from an earlier gospel. What is more

significant is the way in which the different gospel authors modified those

stories to support their own theologies.

Meanwhile, Luke and Matthew share some

230 verses that are not contained in

Mark (Stanton 1989:86). Textual analysis of these verses over the past century

has led scholars to conclude that Matthew and Luke borrowed the stories

contained in these verses from a common source other

than Mark, just as they borrowed the bulk of their stories from Mark. This other

source, which is yet to be discovered, is referred to as "Q"

[short for Quelle,

which means "Source" in German]. There are

several reasons for this consensus. Stanton (1989: 86-87) points out some of

them:

|

1. |

A very close verbal agreement exists between Matthew

and Luke extending over several verses. (e.g., Matt 3:7-10 = Luke 3:7-9; Matt

11:4-11, 16-19 = Luke 7:22-28, 31-350).

|

|

2. |

Striking agreements exist in the order in which the

non-Marcan traditions are found in both Matthew and Luke.

|

|

3. |

Both Matthew and Luke contain

several "doublet" passages in which the two authors use the Marcan form of the

story at one point in their gospel and the Q version of the same story elsewhere

(e.g., "He who has, to him will more be given" Mk 4:25 = Matt 13:12 = Luke 8:18.

A similar saying is found at Matt 25:29 and Luke 19:26).

|

Such

similarities are highly unlikely to have occurred by chance.

The Synoptic Gospels vs. the "Signs" Gospel of

John

As Aviezer Tucker (2016: 137) so eloquently

notes, "The problem

with the Synoptic Gospels as evidence for a historical Jesus . . . is that

the evidence that coheres does not seem to be independent, whereas the evidence

that is independent does not seem to cohere." With the addition of the Gospel of

John, a distinctly independent source, gospel coherence completely disappears.

To begin with, in the

Synoptic Gospels Jesus is more human; in John he is more divine. Indeed, in

John, the very first verse of the gospel proclaims,

"In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with

God, and the Word was God." (John 1:1) In other words,

Jesus is one with God (which he is not in any of the Synoptics) and has always existed.

He simply becomes human through an undefined process:

"And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us."

(John 1:14) There is, therefore, no birth story in

John because, as God, Jesus clearly pre-existed Joseph and Mary. This stands in

sharp contrast to the Synoptics where Jesus is born [in Matthew and Luke]

through a very human process, experiences very human travails, and becomes God's

messenger at different times during his life (at his birth, his baptism, or his

resurrection). In fact, it is not clear when (or even if) Jesus becomes divine

in Mark. The most that can be said is that he becomes a messenger of God at his

baptism.

In those days Jesus came

from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan. And when he

came up out of the water, immediately he saw the heavens opened and the Spirit

descending upon him like a dove; and a voice came from heaven, "Thou

art my

beloved Son; with thee I am well pleased."

(Mark 1:9-11)

Matthew reproduces Mark's description of Jesus' baptism almost exactly, but

changes God's words ("this"

replaces

"thou") in order to have God address the entire

crowd present at the baptism rather than Jesus alone, as in Mark.

And when Jesus was

baptized, he went up immediately from the water, and behold, the heavens were

opened and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove, and alighting on him;

and lo, a voice from heaven, saying, "This is my beloved Son, with whom I am

well pleased." (Matt 3: 16-17)3

Whereas in the Synoptics Jesus suffers and frequently displays his humanity, in

John Jesus is more fully divine and in control of all events, including his own

trial, where he tells Pilate, "You would

have no power over me unless it had been given you from above"

(John 19:10). In the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus even questions his mission and

requests that he not have to suffer crucifixion (Mark 13:36; Matthew 26:39; Luke

22:42). No such doubt exists in Jesus' mind in John, and, consequently, no agony

in the Garden of Gethsemane takes place in the Fourth Gospel. In the Synoptics, Jesus

recruits his apostles; in John, they come to him. None of the spectacular

miracles in John, such as the raising of Lazarus from the dead, are mentioned in

the Synoptic Gospels. Conversely, Jesus performs no exorcisms and tells no

parables in John's gospel, whereas exorcisms and parables permeate and even

define Jesus' teaching in the Synoptic Gospels. According to Vermes (2013: 9),

the Fourth Gospel eschews any discussion of exorcisms because "such a primitive

activity was below the quasi-heavenly dignity of Jesus." Similarly, while the phrase

"kingdom of God" appears some 100 times in the

Synoptic Gospels and forms a central element in Jesus' eschatological teaching

throughout these gospels, it is only mentioned once (in passing) in the Fourth

Gospel (see John 3:1-5). Finally, in John's gospel Jesus talks not in parables, but in long

monologues. In fact, not a single statement made by Jesus in John is contained

in any of the three Synoptic gospels. The repetition of long monologues and the

complete lack of overlap with the words and deeds of Jesus in the Synoptic

Gospels are two of the reasons why not a single quote in the

entire Gospel of John was considered authentic by the 76 scholars of the

Jesus Seminar (1993).

Furthermore, Jesus' miracles are repeatedly performed in John as "signs" of his

divinity, which they never are in any of the Synoptics. In fact, in Mark

(8:11-13) and in Matthew (12:38-39; 16:1-4) Jesus explicitly rejects all requests

that he provide a sign of his divinity.

The

Pharisees came and began to argue with him, seeking from him a sign from heaven,

to test him. And he sighed deeply in his spirit, and said, "Why does this

generation seek a sign? Truly, I say to you, no sign shall be given to this

generation." And he left them, and getting into the boat again he departed to

the other side.

(Mark 8:11-13)

Then some of the scribes and

Pharisees said to him, "Teacher, we wish to see a sign from you." But

he answered them, "An evil and adulterous generation seeks for a sign; but no

sign shall be given to it except the sign of the prophet Jonah. . ."

(Matt

12:38-39)

And

the Pharisees and Sadducees came, and to test him they asked him to show them a

sign from heaven. He answered them,

"When

it is evening, you say, 'It will be fair weather; for the sky is red.' And in

the morning, 'It will be stormy today, for the sky is red and threatening.' You

know how to interpret the appearance of the sky, but you cannot interpret the

signs of the times. An evil and adulterous generation seeks for a sign, but no

sign shall be given to it except the sign of Jonah." So he left them and

departed.

(Matt 16:1-4)

Jesus is also much more explicit and forthcoming about who he

is in John's gospel. There are, for example, 46 "I am"

statements in John where Jesus proclaims who he is openly for all to hear,

compared to only 2, 5 & 2 respectively in Mark, Matthew & Luke. In fact, in Mark

Jesus repeatedly tells those that he has cured or who have witnessed his

miracles not to tell anyone. (Mark 1:44; 3:12; 5:43; 7:36; 8:30). Examples of

"I

am" statements made by Jesus in John, but not

presented in any of the other gospels, include:

Jesus said to them, "I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never be

hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty. (6:35)

Again Jesus spoke to them, saying, "I am the light of

the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness but will have the

light of life." (8:12)

He said to them, "You are from below, I am from above;

you are of this world, I am not of this world. (8:23)

Jesus said to them, "Very truly, I tell you, before

Abraham was, I am." (8:58)

The Father and I are one." (10:30)

[the verb form is different here because the subject is

plural]

Jesus said to her, "I am the resurrection and the life.

Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live. (11:25)

Jesus said to him, "I am the way, and the truth, and

the life. No one comes to the Father except through me. (14:6)

Finally, whereas Jesus is largely misunderstood in the Synoptics, especially in

Mark, he is immediately recognized for who he is in John. This contrast is

especially stark when comparing Mark (the earliest of the canonical gospel) to

John (the latest). In Mark, at one point Jesus' family thinks he is crazy and

tries to stop him from preaching: "and when his

friends heard of it, they went out to lay hold on him: for they said, He is

beside himself." (Mark 3:21) In addition, his

own apostles did not understand who he is, even though they were specially chosen

by him (Mark 3:13-19) and received instruction from him (Mark 4:10-20). When

Jesus calmed a violent storm, they asked, "Who then

is this, that even the wind and sea obey him?"

(Mark 4:41) When they saw Jesus walking on the water, they still did not

understand (Mark 6:49-52). Indeed, Jesus expressed frustration at their lack of

understanding: "Do you not yet

understand?" (Mark 8:21). By contrast, in John

people recognize who Jesus is from the start. As indicated previously, he did

not recruit his apostles in John; they came to him. Furthermore, following

Jesus' first miracle in the fourth gospel, that of turning water into wine, the

evangelist states, "This,

the first of his signs, Jesus did at Cana in Galilee, and manifested his glory;

and his disciples believed in him"

(John 2:11), a direct

contradiction to the statements in Mark. Also, in

John (4:9-10, 22-23), Jesus shares a cup of water with a Samaritan woman and

tells her that she will be with him in heaven. Later, when the woman tells

other Samaritans about Jesus, they invite Jesus to stay in their village, which

(in direct contradiction to Mark and Matthew) he does for two days. They

also immediately believe in Jesus as the messiah, so charismatic is his presence

(John 4:39-40), again in direct contrast to Mark and Matthew where Jesus' message is

rejected by his contemporaries, Jew and Samaritan alike. Indeed, in

Matthew (10:5-6), Jesus explicitly instructs his apostles to stay away from the

Samaritans.

These twelve Jesus sent out, charging them, "Go nowhere

among the Gentiles, and enter no town of the Samaritans, but go rather to the

lost sheep of the house of Israel.

While many Christians want to explain

away the contradictions as simply the result of individual authors presenting

different interpretations of the events they witnessed, the gospels differ

sharply on concrete empirical details, such as the year Jesus was born, who

his ancestors were, the date on which the Last Supper took place, words spoken

at Jesus' trial, the number and names of those who visited his tomb on Easter morning,

and where and to whom Jesus made his post-resurrection appearances.

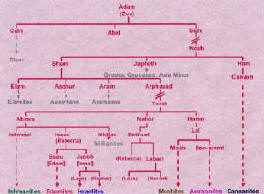

Mark, for example, begins his gospel with Jesus' baptism by John the Baptist and

says nothing about a virgin birth in Bethlehem or about any of the other marvels

and miracles surrounding Jesus' birth that were later added to the "Jesus Story" by Matthew and Luke. Paul, the

earliest Christian writer, also mentions none of these events. Similarly,

while Mark makes no mention of Jesus' ancestry, Matthew (1:1-17) introduces a

genealogy that traces Jesus' ancestry through Joseph all the way back to King

David and to Abraham, the founding patriarch of the Israelites. Luke (3:23-38)

provides an equally inventive genealogy [which includes no names contained in

Matthew's genealogy] that traces Jesus' ancestry clear back to

Adam. Luke even adds Zechariah and Elizabeth to Jesus' family tree as his maternal

uncle and aunt and John the Baptist as his first cousin (Luke 1:36-45).

Similarly, each gospel names distinct individuals who went to Jesus' tomb on

Easter morning:

"Mary

Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salome,"

(Mark 16:1);

"Mary Magdalene and the other

Mary." (Matt 28:1);

"Mary Magdalene and Joanna and Mary the mother of James and the other women."

(Luke 24:8-10);

and first

"Mary

Magdalene" and then

"Simon

Peter and the other disciple, the one whom Jesus loved"

(John 20:1-2). In addition,

while Mark (16:9-18), Luke (24:1-53) and John (20:11-29) all have Jesus'

post-resurrection appearances take place in and around Jerusalem, Matthew

(29:16-17) describes only one appearance, which takes place in Galilee.

The Evolution of the Jesus Story

Contradictions within and between the gospels result from their being

composed, either in whole or in part, at different times and places where various local traditions, together

with the different theologies of each evangelist, resulted in the emergence of

distinct stories and beliefs about Jesus. As traditions about Jesus were passed

down, new stories were added and existing stories became modified and more

elaborated. As a result, the Jesus Story became increasingly mythologized

in conformity with the evolving theology of the Christian community.4

With regard to the birthplace of Jesus, for example, Mark repeats the phrase

"Jesus of Nazareth"

throughout his gospel (cf. 1:9; 1:24; 6:1; 10:47; 16:6), giving no indication

that Jesus was born or lived anywhere but Nazareth. Mark contains none of what

Asimov (1969: 903) refers to as Matthew's "Old Testament pedantry," i.e., his

tendentious application of Old Testament prophecy to significant events in

Jesus' life, including his birth. Nor do we see in Mark any of the angelic

visitations presented in Luke. Since there is no birth story in Mark, there are

no star, magi or shepherds in the fields, no slaughter of innocent children, and

no flight to Egypt by Jesus' family. Nor are there any post-resurrection

appearances by Jesus to his apostles. Mark's gospel ends with the two Marys

(Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of James and Salome --who

was Jesus' mother (see Mark 6:3, 15:40; Matthew 13:55)--

fleeing the tomb and telling no one what they saw (Mark 16:8).5

Indeed, if one were to read only Mark, he or she would have no indication that

Jesus lived or was born anywhere but Nazareth, or that he was anything but a

noteworthy Galilean preacher whose ministry was cut short by Roman authorities

who executed him in the prime of his life, as they did many other messianic

pretenders (see Barnett 1981; Horsley and Hanson 1985). Furthermore, Jesus is presented twice

in the gospel of John (7:41-42, 52) with a challenge to his being the Messiah

based on the belief that the Messiah was to come from Bethlehem, not Galilee.

This would have been a perfect opportunity for Jesus to mention his birth in

Bethlehem, had it been true. However, Jesus says nothing to rebut his critics.

Nor is Jesus' birth in Bethlehem mentioned anywhere else in the entire New

Testament. Indeed, Jesus' birth in Bethlehem, as well as all the other

features of the two infancy narratives, are not mentioned even once outside

those narratives in the very gospels in which they appear.6 This has led some

scholars to argue that the infancy narratives were later additions to Matthew's

and Luke's gospels, just as Chapter 1: 1-18 (the

Prologue) and the

entirety of Chapter 21 are widely accepted as later additions to the gospel of

John.7

As

already indicated, as part of the evolution of the Jesus Story,

Matthew and Luke created elaborate narratives surrounding the birth of Jesus that

not only introduce material not contained in Mark, but that flatly contradict

one another. Other Christian documents were also created that added material to the

infancy narrative that was not contained in either Matthew and Luke.

The

Protevangelium of James,

a second-century Christian document (originally attributed to James, Jesus'

brother) adds the birth of Mary (Jesus'

mother) to Joachim and Anna to the Jesus Story and introduces additional material

not contained in

the nativity stories of Matthew and Luke. According to the

Protevangelium (3:1-7), Anna bemoans her barrenness. As later happened to her daughter Mary, however, she

was visited by an angel who informs her that she will give birth to a progeny who

"shall be spoken of in all the world."

(4:1). Subsequently, when Mary was three years old, she was

brought to the Temple in Jerusalem to be raised as a virgin and nourished there

by angels before being betrothed to Joseph. When she was received in the Temple,

the High Priest "received her, and blessed her,

and said, 'Mary, the Lord hath magnified thy name to all generations.'"

(7:4). When she reached age 14, Joseph was chosen to be

her bridegroom. Joseph was chosen over the many available men because a dove emerged from his staff among all those

presented

to the High Priest by men throughout Judea. As a result of this "sign",

the High Priest says to Joseph, "Thou art the

person chosen to take the Virgin of the Lord to keep her for him."

(8:12).8 Joseph, however, initially refuses on the grounds

that he was an old man and already had children (7:13). During the trip from Nazareth to Bethlehem for the census

(borrowed from Luke), Mary and Joseph are accompanied by Joseph's sons.

However, Mary and Joseph only made it to

the half-way point, when

"Mary said to him: 'Joseph, take me down from the ass,

for the child within me presses me, to come forth.'"

Joseph helped her down from the ass and asked,

"Where shall I take you and hide your shame? For this

place is a desert"

(17:8). Joseph then locates a

nearby cave where he takes Mary, and it is in this cave, in a desolate area three miles

north of

Bethlehem [not in Bethlehem itself, where Jesus was born in the gospels of

Matthew and Luke], that Mary gives birth to Jesus.9

The

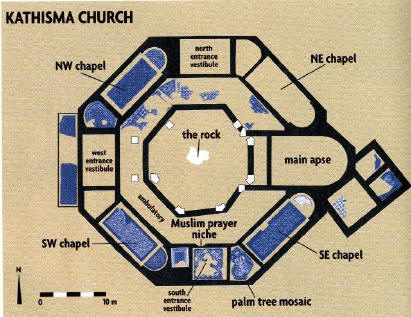

Protevangelium's version of the nativity story inspired the building of the church of the

"Kathisma of the Theotokos"

("Seat of the God-Bearer")

in the 5th century some three miles north of

Bethlehem to mark the place where Mary paused to give birth

to Jesus (Shoemaker 2001, 2003; see photos below). At the center of the ruins of the

Kathisma Church is a rock believed to be the seat upon which Mary rested before

giving birth, though there is nothing in the Protevangelium that

would suggest the existence of a seat or of Mary sitting (Shoemaker 2003:23).

|

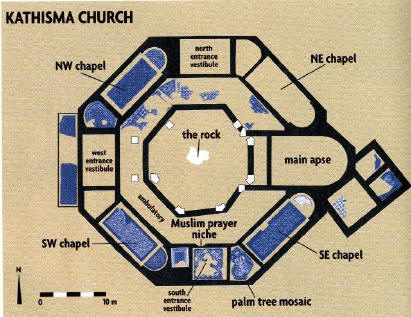

Kathisma Church Ruins

|

Kathisma Church Diagram |

|

.jpg)

"Mary's Seat"

|

The midwife attending Jesus' birth is made aware of Jesus'

identity and of his miraculous birth, to which she replies,

"This day my soul is magnified, for mine eyes have

seen surprising things, and salvation

is brought forth

to

Israel." (14:10). The midwife tells another

midwife named Salome about the virgin

birth, but the latter disbelieves her, causing Salome's hand to wither. Salome's hand

is only rejuvenated after she touches the Christ child [in much the same way

that in

Luke's gospel Zechariah's dumbness was cured when he finally believed in

Elizabeth's divine pregnancy with John the Baptist].

The

Protevangelium's version of the nativity story was to have a significant

effect on later Muslim beliefs regarding the nativity story.

As Shoemaker (2003: 17) notes, "this early

Christian tradition of Christ's birth in 'a desert' is almost certainly the

source of the Qur'anic tradition of Jesus' birth in a 'remote place.'"

The

Qur'anic Nativity Tradition

And so she

[Mary] conceived him, and she withdrew to a remote place with him. Then labor

pains drove her to the trunk of a date palm. She said, "Would that I had died

before this and was completely forgotten!" Then one cried out to her from

beneath her, "Do not be sad: your Lord has placed a brook beneath you. And shake

the trunk of the date palm towards you: it will drop ripe dates on you. So eat

and drink and be glad. And if you should meet any person, say, 'Behold, I have

vowed a fast to the Merciful one, so I will not speak to any person today.' And

she brought him to her people, carrying him.

(quoted in Shoemaker 2003: 17)

The

Protevangelium adds additional details to Matthew's story of Herod's slaughter of Hebrew children

(16:1-17).

Just as Mary and Joseph fled with their child to Egypt, Elizabeth fled with her

child (John) to the mountains. Unable to scale the mountains, Elizabeth calls out

to God, who caused the mountains to split so that she could enter. God then sent

an angel to protect her and her child (see 16:3-8). In the meantime, Herod sent his servants

to Zechariah to discover the whereabouts of John, and then had Zechariah killed

when he refused to tell them where John was, with Zechariah proclaiming,

"I

am a martyr for God, and if he shed my blood, the Lord will receive my soul"

(16:14).

In

yet another elaboration of the Jesus Story, the second-century

Infancy Gospel of Thomas contains

accounts of 17 miracles performed by Jesus between the ages of 5 and 12, and

ends with a more elaborate version of the tale told by Luke (2:40-52) of the

young Jesus in the Temple. In this gospel, Jesus is a mostly

mischievous child who causes harm, and even death, to individuals who displease

him. Jesus caused one child's body to wither because that child destroyed fish

pools that Jesus had created and caused another boy to die who bumped into Jesus

while running past him. In both cases Jesus reversed his actions when Joseph

was confronted by the aggrieved children's fathers. Thus, in both his destructive and curative

actions, the child Jesus displays his miraculous powers.

The

Infancy Gospel of Thomas also adds three prescient stories to the

expanding infancy narrative:

1. The gospel

relates a story concerning Jesus' circumcision following his birth in which

Jesus' foreskin is preserved by his mother in an alabaster jar that later turned

out to be the very jar used by the

"Sinful Woman" to

wash the feet of Jesus (2:4; see Luke 7:36-50).

2. In another

story, Jesus' family passes through a country infested with robbers during their

return from Egypt and encounter two thieves: Titus and Dumachus. Titus pleads

with Dumachus to let the family proceed unharmed, but the latter refuses. In

response to his kindness, Mary said to Titus,

"The Lord will receive thee to his right hand, and

grant thee pardon of thy sins" (8:5). The infant Jesus then proclaims that

"When thirty years are expired, O mother, the Jews will

crucify me at Jerusalem; and these two thieves shall be with me at the same time

upon the cross. . . . and from that time Titus shall go before me

into paradise" (8:6-7), thus adding a

prediction made during Jesus' infancy to an event described in the gospel of

Luke (23:39-43).

3. In yet

another prophetic story (14:1-10), a young boy possessed by the

devil was biting other children. He was brought to Mary by his mother in hopes

that she could help. However, while he was there, he tried to bite Jesus,

but struck Jesus on his right side instead when prevented from biting him. The

boy was Judas Iscariot, who was later to betray Jesus, and the spot upon which

he struck Jesus was the very spot in which Jesus was pierced with a spear while

on the cross (John 19:34).

The

Syriac Infancy

Gospel, dating perhaps to the

5th or 6th

century, combines features taken from the infancy narratives of Matthew and Luke, the

Protevangelium of James, and the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, and adds

new elements not contained in any of these earlier narratives. The Syriac

Infancy Gospel gives special attention to the magical and curative

powers associated with Jesus' swaddling clothes and with the various waters used

to bathe Jesus. The magi,

for example, were given one of Jesus' swaddling clothes by Mary in return for

the gifts they brought to the Christ child. Upon returning to Persia, these clothes

were placed in a ritual fire, but survived unscathed (3:6-8). A boy is later cured

of possession by multiple devils when some of Jesus' clothes are draped over his head:

"the devils began to come out of his mouth, and fly

away in the shape of crows and serpents" (4:16). On another occasion, Mary made a coat out of Jesus' clothes for a woman's son who

was ill; the son was immediately cured of his illness when he wore the coat (10:1-3). Yet another child is saved from death just by being placed on a bed

in

which Jesus had previously lain (11:6). In a similar

manner, a young girl is cured of leprosy when she is bathed in water previously used to

wash Jesus (6:18). Her mother tells a prince's wife, whose

son also suffers from leprosy, and he too is cured when his mother pours Jesus'

bath water over him (6:33-34). Several other examples of

miraculous cures resulting from contact with water in which Jesus was washed are

also presented (cf. 9:1-5; 12:1-6, 20).

The

Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew,

(originally titled,

The Book About the Origin of the Blessed Mary and the Childhood of the

Savior), written c. 600-625 CE (Klauck

2003:78), adds yet more new material to the nativity story.

The Gospel of Ps-Matthew is largely a

re-working of the Protevangelium of James, but with several significant

changes. According to Kleuck (2003: 79), these changes include:

1. The removal of any ambiguity regarding the

conception of Mary. The Angel emphatically tells Joachim (her father) that his

wife has "conceived a daughter of your seed."

(3:2)

2. In 13:3, after

carrying out her investigation, the skeptical midwife explicitly affirms the

physical virginity of Mary: "She conceived as a

virgin, she remains a virgin." (This was in

concordance with DS 503 adopted by the Lateran Synod in 649 CE).

If anyone does not in accord

with the Holy Fathers acknowledge the holy and ever virgin and immaculate Mary

was really and truly the Mother of God, inasmuch as she, in the fullness of

time, and without seed, conceived by the Holy Spirit, God in the Word Himself,

who before all time was born of God the Father, and without loss of integrity

brought Him forth, and after His birth preserved her virginity inviolate, let

him be condemned.

3. Ps-Matthew elaborates on the

ox-manger presented in the Protevangelium in a way that was to affect nearly every artistic representation of the birth of Jesus

in later centuries. It places the ox and ass directly alongside Jesus' crib,

citing two prophetic quotations (14:2).

a.

On

the third day after the birth of the Lord, Mary left the cave and went into a

stable. She laid the boy in a crib, and ox and ass venerated him. This fulfilled

the words of the prophet Isaiah: "The ox knows its master, and the ass knows the

crib of the Lord."

(Isaiah 1:3)

b.

The

animals received him into their midst and venerated him without ceasing. This

fulfilled the words of Habakkuk:

"In the midst, between two animals, you shall

be known."

(Hebrews 3:2, according to the Septuagint).

4.

The timing of Mary's pausing is moved from the nativity of Jesus to the holy

family's flight to Egypt.

According to Ps-Matthew, Mary became

hungry during the holy family's flight to Egypt, just as the family arrived at a

desolate area in the midst of the desert north of Bethlehem. In response to his

mother's hunger, the infant Jesus caused a tall date palm to bend and offer her its

fruit.

Miracle of the Palm Tree on the Flight

into Egypt

(unknown Sculptor)

(c. 1490-1510)

(Spanish)

New York

Metropolitan

Museum of Art

In some versions of the story, Mary also drinks from a spring that

the infant Jesus miraculously provides from the roots of the palm. Jesus

then rewards

the date palm for its obedience by transferring it to Paradise

(Ch. 20).

Significantly, reference

to this flowing water is contained in the

Piacenza Pilgrim, an

early medieval pilgrimage guide composed between 560-570 CE.

On the way

to Bethlehem, at the third milestone from Jerusalem, lies the body of Rachel, on

the edge of the area called Ramah. There I saw standing water which came from a

rock, of which you can take as much as you like up to seven pints. Everyone has

his fill, and the water does not become less or more. It is indescribably sweet

to drink, and people say that Saint Mary became thirsty on the flight into

Egypt, and that when she stopped here this water immediately flowed. Nowadays

there is also a church building there. (quoted in Shoemaker 2003: 22)

Below are two 16th century paintings from the

Netherlands in The National Gallery of Art

in Washington, D.C. that portray Mary resting during the flight to Egypt.

|

%20(cropped).jpg)

The Rest on the Flight to

Egypt

(Gerard David, c. 1510)

|

%20(cropped).jpg)

The Rest on the Flight to

Egypt

(Maerten Heemskerck, c. 1530) |

5. The gospel

also adds several items to the story of the family's return from Egypt that are

not contained in any previous document.

a. In Chapter 18, the infant Jesus tames many dragons

that emerge from a cave and frighten the children who are traveling with the

holy family.

b. In Chapter 19, Jesus is served by lions and

panthers who show the travelers their path and refrain from molesting the oxen,

asses, beasts of burden, sheep and rams which Jesus' prosperous family have

taken with them. This purportedly fulfilled the prophetic promise of an eschatological peace

among the animals.

The wolf

will live with the lamb, the leopard will lie down with the goat, the calf and

the lion and the yearling together;

and a little child will lead them. The infant will play near the cobra’s den,

and the young child will put its hand into the viper’s nest. They will neither

harm nor destroy on all my holy mountain, for the earth will be filled with the

knowledge of the Lord as the waters cover the sea. (Isaiah 11:6-9)

c.

When the journey becomes too arduous,

Jesus shortens the way, so that a 30-day journey takes only one day (Ch. 22).

d.

As Jesus enters one city in Egypt, all the idols (idola) crash to the

ground and are broken in pieces (Ch. 23), accompanied by a quotation from Isaiah

(19:1).

See, the Lord rides on a

swift cloud and is coming to Egypt. The idols of Egypt tremble before him, as

the hearts of the Egyptians melt with fear.

(Isaiah 19:1)

This action does not move the ruler of the city to

anger; rather, he and the entire population

"come to faith." (Ch. 24)

As

previously indicated, most scholars believe that the inspiration for the

building of the Kathisma Church was the story of the travel of the holy family

from Nazareth to Bethlehem, as presented in the Protevangelium of James

in which Mary gives birth in a cave before reaching Bethlehem. The

earliest reference to to the Kathisma Church and to its liturgical function is

found in the 5th century Jerusalem Armenian Lectionary.

The readings associated with the feast celebrated at the church, which included

Isaiah 7:10-16 and Galatians 3:29-4:7, plus several homilies given

by Jerusalem priests [in both Greek and Georgian], clearly demonstrates the

church's original liturgical connection to the birth of Jesus through Mary

(Shoemaker 2001: 52-54). However,

the interpretation of the church as a sacred site changed over time. With the

construction of the basilica at Bethlehem by

Constantine (325 CE; rebuilt by Justinian ca. 550 CE) and the official

celebration of the nativity at this latter site, the interpretation of the

Kathisma Church changed from celebrating Jesus' birth to commemorating the

holy family's flight to Egypt, as represented in the Gospel of Ps-Matthew.

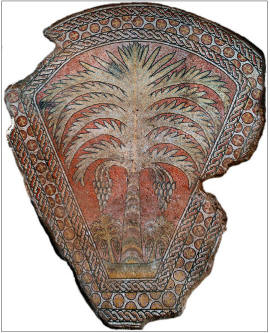

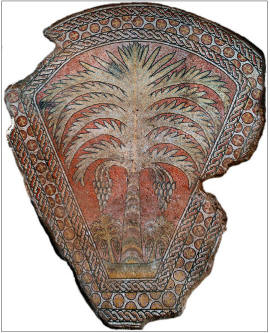

The story of the palm tree, contained in Ps-Matthew but not in the

Protevangelium, is reflected in the presence of the mosaic of

a large date palm (accompanied

by two smaller palms, all of which are laden with fruit)

on the floor of the church (Shoemaker 2003: 33; see illustration below).

Significantly, the palm mosaic is

the only pictorial

mosaic discovered in the church. All the other mosaics are geometric in

design. Equally significant, the current mosaics in the church were installed

during the 8th century, when it was converted into a mosque (Shoemaker 2003:

34).

Furthermore, inasmuch

as the Kathisma Church is located three miles to the north of Bethlehem, it

would be illogical for Jesus' family to have stopped at this location when they

were fleeing south to Egypt. Eventually, the Kathisma Church evolved into

a Marian site commemorating the Dormition

and Assumption

of Mary, completely removed from events surrounding the nativity of Jesus (see

Ray 2000: 94ff.; Shoemaker 2003: 24-31;

Klauck 2003:79).

Palm Mosaic

Mary's encounter with the date palm and spring in the

desert is described near the beginning of this Dormition

narrative. As the narrative opens, Christ, who is identified as a "Great Angel,"

appears to his mother to announce her impending death. When Mary expresses some

uncertainty regarding the angel's identity, the Christ-Angel reassures her by

reminding his mother of their journey

through the desert into Egypt,

when he miraculously fed her from the date palm. Jesus continues by reminding

Mary of Joseph's anger and confusion at the circumstances of her pregnancy,

saying of Joseph that

He (Joseph) was crying

. . . and Joseph was angry with you, saying, 'Give your breast to your

child.' At once you gave it to him, as you went forth to the Mount of

Olives, fleeing from Herod. And when you came to some trees you said to

Joseph, 'My lord, we are hungry, and what do we have to eat in this desert

place?' Then he rebuked you, saying, 'What can I do for you? Is it not

enough for you that I became a stranger to my family on your account; why

didn't you guard your virginity, so that you would [not] be found in this;

and not only you, but I and my children too; now I live here with you, and I

do not even know what will happen to my seven children. . . .

I have been afflicted

from all sides because of you, because I have left my country. And I am

afflicted because I did not know the child that you have; I only know that

he is not from me. But I have thought in my heart, perhaps I had intercourse

with you while drunk, and that I am even worse because I had determined to

protect [you]. And behold, now it has been made known that I was not

negligent, because there were [only] five months when I received you in [my]

custody. And behold, this child is more than five months; for you embraced

him with your hand. (quoted in Shoemaker 2003: 20)

Clear

parallels exist between the legend of Mary feeding from the date palm and stream

in the Gospel of Ps-Matthew and the Qur'anic Nativity account.

However, in the Christian version of this story the event takes place during the

holy family's flight to Egypt and is not connected with the nativity of Jesus.

According to Shoemaker (2001: 29-36), however, the story of the palm tree was

widely dispersed throughout the Byzantine Near East and is contained in several Syriac fragments copied as early as the late 5th century. He attributes the

dispersal of this story to the Qur'an to the significance of the Kathisma Church

in early Palestinian Christianity. According to Shoemaker (2003: 16), only two

sources in Christianity contain reference to the holy family's pausing in the

desert north of Bethlehem: the Protevangelium of James and the Gospel

of Ps-Matthew. However, the

Gospel of Ps-Matthew was likely composed too late to have an impact on

the nativity story in the Qur'an. Furthermore, it was first composed in Latin in

the Christian West and was completely unknown in the Christian East (ibid.:

19). The other principal source, according to Shoemaker, was the Kathisma Church where

early celebrations of Jesus' nativity took place. The significance of the

Kathisma Church in the development of the Qur'anic version of Jesus' birth is

supported by current research that places the

origin of Islam in the Levant rather than in the Hijaz, as is generally believed (see Nevo and Nevo 1994; Berg 1997; Sivers 2003; Shoemaker 2003:

13-14, including

notes 3 & 4).

the

Qur'an's dependence on . . . local Jerusalemite traditions adds

additional weight to revisionist arguments against the origin of Islam in the

Hijaz. As many scholars have demonstrated, . . . the

traditional Islamic narrative of Hijazi origins is both late and problematic

from a historical point of view.

Moreover, various peculiarities of formative Islam that have somehow escaped the

censorship of the later tradition's 'Hijazi nostalgia' point to the beginnings

of Islam somewhere in the Levant, and more specifically in the southern deserts

of Palestine and Roman Arabia. In addition, the archaeological record of

southern Palestine fits more with the traditions of early Islam than does the

Hijaz.

(Shoemaker

2003: 13)

The

parallels between the legend of Mary feeding from the date palm and stream in

the Gospel of Ps-Matthew and the Qur'anic nativity account are clear.

However, the Christian version of this story takes place after Jesus' birth and

is not at all connected with the events of the nativity. The story of Mary and

the Palm is not associated with the events of the nativity in any Christian

tradition. The question then becomes why, if in fact the Qur'an borrowed this

earlier Christian legend, it altered the legend's original setting, transforming

it into a nativity tradition. Ray (2000) shows that this resulted from the

celebration of

"Mary the Theotokos"

(the feast of August 15th) in the early Jerusalem

liturgical cycle. According to Ray (2000: 116-129), the earliest celebrations of

the nativity prior to the 4th century initially took place in the middle of May, were later moved to January, and then finally

moved to December. In its celebration of the feast

of August 15th,

the Jerusalem church appears to have adopted a Roman nativity feast alongside

its own native nativity feast. In the beginning, both the location of the

Kathisma Church and the feast of August 15th were connected primarily with the

nativity. It was later, during the 5th century, that they came to be

celebrated specifically as Marian feasts (Shoemaker 2003: 27).

Comparisons

of the structure of the Kathisma Church and the

Dome of the Rock

in Jerusalem, one of the holiest of Muslim sites, adds considerable weight to

the role that the Kathisma Church played in the transmission of the nativity

story to the Qur'an.

Rina Avner, the

Kathisma church's primary excavator, has demonstrated persuasively that this

fifth-century church served as the primary architectural model for Abd al-Malik's

construction of the Dome of the Rock at the close of the seventh century. At the

most superficial level, there is the not insignificant coincidence that this

church, about an hour's walk from the Temple Mount, is architecturally almost

identical with the Dome of the Rock, right down to the enormous, sacred rock at

its center. Approximately the same size as the Dome of the Rock, the Kathisma

consists of two concentric octagons, centered on a large rock which is itself

enclosed by a third octagon. (Shoemaker 2003: 36-37)

Shoemaker (2003: 38) adds,

not only does the Kathisma appear to have served as

the Dome of the Rock's architectural model, but the unusual mosaics found in

both shrines attest to the strong links between them. In view of the Kathisma's

significance for early Islam, we should not be surprised at all to find that its

traditions have influenced the Qur

'an.

To summarize this complicated process: the elaboration upon Luke's infancy

narrative that is presented in the Protevangelium of James, in which Mary

gives birth to Jesus before reaching Bethlehem, inspired the construction of a

church on the spot where this birth was believed to have occurred. In time,

however, as the official celebration of Jesus' birth became focused on

Bethlehem, the interpretation of the Kathisma Church's meaning changed from the

place where the holy family stopped on its way to Bethlehem to the place where

it paused during its flight to Egypt [despite the illogic of this latter

interpretation]. While this change in meaning was incorporated into the later

Gospel of Ps-Matthew, the original interpretation of the site was

retained in the Qur'an.

Thus,

with each additional document, new stories were added to the infancy narrative,

enhancing the divine nature of Jesus' birth. The

Protevangelium of James, the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, the

Syriac Infancy Gospel and the Gospel of Ps-Matthew all added stories not contained in

either Matthew's or Luke's infancy narratives in the same way that Matthew and

Luke added material (including their infancy narratives) not present in Mark's

gospel or in the non-canonical narratives

that preceded them. With each new account (both canonical and

non-canonical), Jesus became

more clearly divine from the outset, and the events surrounding his birth (as

well as his life and death) became more miraculous and more explicitly part of

God's plan. In this way, the Jesus Story remained a work in

progress for several centuries following Jesus' death.

|

Jesus' Circumcision

(Chartres

Cathedral)

Chartres Cathedral is one of over a dozen

European churches that claimed at one time or another to have possessed Jesus'

foreskin.

Holy Prepuce

|

The Evolution of Jesus in the Gospels

One

way to view the evolution of Jesus as he is presented in the New Testament

is to compare how any individual story is presented throughout the four

canonical gospels.

Many stories, such as those of the Good Samaritan, the Sermon on the Mount, and

the raising of Lazarus from the dead, cannot be compared, because they are

presented in only one gospel. However, other stories, such as the stories of Jesus'

birth, baptism, trial, execution and resurrection, can be compared, because they

are described in multiple gospels. Most stories differ significantly in the

various

gospels, far more than would be expected if the different gospel portrayals

represented the normal variation associated with multiple eyewitness accounts.

Furthermore, differences that occur in one story correlate with differences in

other stories within the same gospel, and together result in multiple versions

of Jesus' life and ministry. Mark's gospel, for example, can best be understood

as an "apology," i.e., an attempt to counter the misunderstanding of Jesus' life

and mission in much the same way that Plato's

Apology had done for Socrates. In Mark,

Jesus dies on the cross in despair, misunderstood and abandoned even by his own

apostles, exclaiming, "My God, my God, why

have you forsaken me?" (Mark 15:34) [the opening

lines of the 22nd Psalm]. This cry is repeated verbatim in Matthew (27:46).

Mark's description of Jesus' last words stands in sharp contrast to those uttered

in Luke (23:46), "Father, into your hands I

commit my spirit," and in John (19:30),

"It is finished," both of which lack the despair

associated with Jesus' cry in Mark. They suggest, instead, the conclusion of a

successful mission. Indeed, Jesus' last words in John are consistent with that

evangelist's portrayal of Jesus throughout the gospel, not as a human being

suffering the travails of an earthly existence, but as God himself carrying out

a pre-ordained plan.

Whereas Mark presents Jesus as mostly a local Galilean preacher chosen by God to

spread his word, the stories in Matthew's gospel repeatedly link Jesus to the

Old Testament, especially to the life of Moses and to the redemption of Israel.

Indeed, Matthew's gospel contains 11 "fulfillment

citations" [explicit statements linking individual

episodes in Jesus' life to prophecies foretold in the Old Testament] that are

not contained in any of the other gospels. Many, in fact,

are rather clumsily added to texts borrowed from either Mark or from Q (see McCasland 1961; Moule

1967; Winter 1954a). Luke's gospel does not include any Old Testament citations

in those passages that Matthew and Luke both borrowed from Mark or from Q.

Whereas in Matthew, Jesus is the new Moses who represents the salvation of

Israel, in Luke Jesus becomes a more universal savior of all mankind, with less

focus on Israel and the Old Testament.10

As a result, Luke places the

significant events in Jesus' life -most notably his birth- more in the context

of the larger Greco-Roman world than does Matthew. Unlike Matthew, where the

stories surrounding Jesus' birth are centered on Herod, the King of Judea, Luke

places Jesus' birth during the census commanded and administered by Caesar

Augustus11 and

Publius

Sulpicius Quirinius, the

Roman emperor and governor of Syria respectively. In addition, stories

displaying a more parochial

focus are replaced in the later gospels by those with more universal

appeal, as Christianity sought to attract

primarily Gentile (non-Jewish) converts. For

example, the story of

Jesus' refusal to cure the daughter of the Syrophoenecian woman because she was

not Jewish (see Mark 7:24-30; Matthew 15:21-28) is absent in the gospels of Luke

and John.

|

Jesus and John the Baptist

Jesus' relation to John the Baptist is another case in point. John increasingly becomes a Christian evangelist as we proceed through the gospels.

In Mark, John's role is simply that of a forerunner to Jesus. In Matthew, the

teaching of Jesus and John are summed up in identical words:

"Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand."

(Matt 3:2 [spoken by John]; Matt 4:17 [spoken by Jesus upon learning of the

arrest of John]). However, while Matthew links John with Jesus as a herald of

the new era of the kingdom, Luke places John firmly in the "old" era of the law

and the prophets, in contrast to Jesus who represents the new

and final era (see Oliver 1964:216-217; Freed 2001:124-127).

In Luke, the good news of the kingdom of God is preached only after John's day

(see Luke 16:16; Acts 10:36-37). Also, while Matthew makes no reference

to John in his infancy narrative, Luke devotes a great deal of space to John's

birth, making him Jesus' first cousin. In addition, while clear parallels exist

in Luke's stories describing the annunciations and births of Jesus and John (see

Freed 2001: 114-115), he juxtaposes those stories in a way that repeatedly

subordinates John to Jesus, the one for whom he is preparing the way. In Luke's

infancy narrative, John even recognizes Jesus' superiority while still in

the womb (Luke 1:44). Similarly, while John's birth is miraculous in that

both of his parents were very old and his mother, Elizabeth, was barren (Luke

1:5, 18), Mary's conception was even more miraculous in that it happened without

any sexual relations at all. According to Luke (1:35), the angel Gabriel

said to Mary, "The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the

power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will

be called holy, the Son of God." Jesus'

superiority over John is repeated yet again in Luke's canticles. In the

Magnificat, Mary sings

"My

soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior . . .

. For behold,

henceforth all generations will call me blessed"

(Luke 1:47-48), whereas in the

Benedictus,

Zechariah, the father of John the Baptist says of his son,

"And you, child, will be called

the prophet of the Most High; for you will go before the Lord to prepare his

ways," (Luke

1:76).

|

|

By

the Fourth Gospel, John has become essentially a Christian evangelist.

There was a man sent from

God, whose name was John. This man came for a witness, to bear witness of the

Light that all through him might believe. He was not that Light, but was sent to

bear witness of that Light.

(John 1: 6-8)

John

even puts words in John the Baptist's mouth in which the latter explicitly

subordinates himself to Jesus, words not spoken by the Baptist in any of the

other gospels.

John answered

and said, "A man can receive nothing unless it has been given to him from

heaven. You yourselves bear me witness that I said, 'I am not the Christ,' but,

'I have been sent before Him.' He who has the bride is the bridegroom; but the

friend of the bridegroom, who stands and hears him, rejoices greatly because of

the bridegroom's voice. Therefore, this joy of mine is fulfilled. He must

increase, but I must decrease. He who comes from above is above all; he who is

of the earth is earthly and speaks of the earth. He who comes from heaven is

above all. And what He has seen and heard, that He testifies; and no one

receives His testimony. He who has received His testimony has certified that God

is true. For He whom God has sent speaks the words of God, for God does not give

the Spirit by measure. The Father loves the Son, and has given all things into

His hand. He who believes in the Son has everlasting life; and he who does not

believe the Son shall not see life, but the wrath of God abides on him."

(1:27-36)

The

Fourth Gospel also has John proclaim Jesus as

"the Lamb of God" (John 1: 29, 36) who takes

away the sins of the world, again a phrase not used in any of the other gospels.

John the Baptist's witness to Jesus as the "Lamb of God" in the

Fourth Gospel

even results in two of John's own disciples leaving him to follow Jesus. Andrew

brings his brother Simon Peter to Jesus with the words

"We have found the Christ"

(1:40-42). Significantly, they follow Jesus, not as a result of Jesus' call to

them (as in Mark 1:16-20; Matt 4:18-22; Luke 6:12-16), but in response to John's

witness.

Inasmuch as all descriptions of the Baptist in the gospels were written by

Christian evangelists, not by followers of John, it is unclear what the actual

relation between Jesus and John was. The initial pre-eminence of John in

first-century Palestine is demonstrated by the fact that it was he who baptized

Jesus, not the other way around. Significantly, while Josephus, the

principal Jewish historian of the first century CE in Palestine, provides an

extensive and laudatory description of John the Baptist in his

Antiquities of the Jews

(18.5.2), his description of Jesus (18.3.3) is considered by most scholars to be

a forgery inserted later, either all or in part, by Christian scribes. (see Abruzzi,

The Jesus Movement:

#7). Some

scholars believe that Jesus was

originally a follower of John (cf. Tabor 2006).

If Jesus was

born the "Son of God" through an Immaculate Conception (Luke 1:35) and was,

therefore, by definition, free of sin, he would have had no need to be baptized

by John, since all three synoptic gospels are quite explicit that John baptized

people specifically as repentance for the forgiveness of their sins (Mark 1:4;

Matthew 3:11; Luke 3:3).

If, however, Jesus were originally a follower of John, then his being baptized by John

would have made sense.

And so

John the Baptist appeared in the wilderness, preaching a baptism of repentance

for the forgiveness of sins.

The

whole Judean countryside and all the people of Jerusalem went out to him.

Confessing their sins, they were baptized by him in the Jordan River.

(Mark 1:4-6)

People went out to him from Jerusalem and all Judea and the whole region of the

Jordan. Confessing their sins, they were baptized by him in the Jordan River.

(Matt 3:5-6)

He went into all the country

around the Jordan, preaching a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of

sins. (Luke 3:3)

No evidence exits that

John ever became a follower of Jesus. Quite the contrary; there

is ample evidence that John's mission survived his death and that as late as the second century some groups

claimed John, not Jesus, as the Messiah (see Brandon 1951: 24-26;Hughes 1972:

213-214; Stanton 1989:167). Indeed, both Paul

and the author of Acts discuss

Apollos, a prominent Jewish Christian from Alexandria and

12 disciples whom Paul met in Ephesus who knew only of John's baptism, not that of Jesus

(see note #12 below). All four of the

gospels also distinguished clearly between the disciples of Jesus and those of John

(see Freed 2001:133), and both Mark (6:29) and Matthew (14:12) state explicitly

that following his execution John's disciples "came and took his body and buried it."

In addition, Hughes (1972) draws a sharp distinction between the teaching of

Jesus and that of John, noting that Jesus could not have been the object of

John's preaching. Hughes argues that it was Yahweh himself, not Jesus, who

was the "Coming One"

prophesized by John. John, like Jesus, preached the imminent end of days, i.e.,

the coming of God's Kingdom. John preached in typically Old Testament style,

frequently using Old Testament metaphors, including a claim that the Coming One

would bring a "baptism of fire."

John thus taught that everyone must repent and prepare

for the coming of God's kingdom. Jesus would clearly not have fit John's view of

the Coming One. John preached an ascetic lifestyle and the abandonment of the

pleasures of the day as a way to prepare for the coming of God's kingdom. Jesus,

who lived in cities, attended banquets and parties, and who associated with all

manner of sinners, clearly did not fit John's notion of how one should comport

themselves in preparing for the coming of God's kingdom, let alone represent the

very essence of that kingdom.

A rivalry may have existed between the disciples of Jesus and those of John. The increasing Christianizing and subordination of John to

Jesus throughout the Christian gospels may well have been the evangelists' way of

dealing with that competition, i.e., by increasingly promoting the notion that not only

John's apostles, but John himself, recognized Jesus as the Messiah. The

Fourth Gospel

(John 3:30) even has the Baptist go so far as to say, "He

must increase, but I must decrease."

And since no

documents produced by followers of John the Baptist survive to provide an alternate

view, the Christian view of John has prevailed. However, even if such documents

did at one time exist, they would likely have been destroyed, as this was the fate that befell

many

documents the later church considered heretical (see Bauer 1934; Ehrman 1993). Thus, the only story of John that comes down to

posterity is the Christian story, because, as Elaine Pagels (1979:179) notes,

"It is the winners who write history -their way."

Contradictions Among the Gospels

Obvious contradictions would be expected to result from the fact that the four

gospels, representing four distinct theologies, present different versions of

John and of his relation to Jesus, The first and most obvious is the fact that,

despite John's explicit statement regarding his subordination to Jesus, whom he

claimed in the fourth gospel was the true messiah, John never became a follower

of Jesus, but rather, as just indicated, maintained his separate mission until he was executed by

Herod Antipas (c. 29 CE).

In addition, whereas the author of the gospel of John

(1:27-36, see above)

presents John the Baptist as absolutely

understanding who Jesus was and explicitly acknowledging his own subordinate

role to Jesus, in both Matthew (11:2-6) and Luke (7:19-23) [in passages likely

borrowed from Q], while in prison the Baptist sends emissaries to Jesus to ask him, "Are you he who is

to come, or shall we look for another?"

Similarly, as already mentioned, whereas Jesus recruits his apostles in the three Synoptic Gospels

(Mark 1:16-20; Matt 4:18-22; Luke 6:12-16), they seek him in the fourth gospel

(John 1:40-42). Likewise, in Mark's (1:9-11) version of Jesus' baptism by John,

the Baptist gives no indication that he knew who Jesus was. Even in the fourth gospel

(John 1:32-34), John explicitly claims not to know who Jesus was, being simply

instructed by the Holy Spirit to baptize him. Yet, as already mentioned, John is introduced near the

beginning of Luke's Gospel (1:36-42) as Jesus' first cousin. This level of

contradiction is multiplied many times over when comparing all the stories

contained in more than one gospel.

Also,

when reading and interpreting New Testament texts, it is necessary to recognize

that those biblical documents that have survived and that are used by millions of

Christians today are but a small fragment of the totality of early Christian

writings that have been produced.

Numerous writings, referred to collectively as Christian

Apocrypha

and Pseudoepigrapha

exist that did not become incorporated into the New Testament. These

non-canonical writings include more than two dozen gospels, as well as numerous

epistles, acts of various apostles, apocalypses and homilies written in the

early years of the church (see Davies 1983; Barnstone 1984; Robinson 1984;

Hone, Jones & Wake 1979; Cartlidge 1997; Hedrick 2002; Ehrman 2003a, 2006b; 2013). These various documents were

used among a variety of Christian communities before there was an

official New Testament. Some of these writings have survived and some have been

rediscovered (such as the remarkable discoveries of the Nag Hammadi Scrolls in

1945 and the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947). However, many of these documents were

destroyed by the Roman Church as it consolidated its power within the empire, or

have been otherwise lost, and are known to us only through references to them by

numerous early Christian writers, such as Tertullian, Irenaeus and Origen. These diverse writings contain a host of stories about

Jesus, Mary, Joseph, Mary's parents, Mary